You are here

Preserving Ancient Documents

The fifth and sixth doors of the Grande Galerie de l’Evolution building, located in Paris’s Jardin des Plantes, are home to one of the country’s main institutions for heritage preservation: the CRCC,1 a Mecca for conservation. Here, chemists, physicists, and microbiologists combine their efforts to study how graphic material and other documents deteriorate over time. The Center was founded in 1963 to analyze the mold that had ravaged libraries during the Second World War. A better understanding of the phenomenon would enable scientists to slow it down and, eventually, contain it.

Rock, paper, preserve

Since its creation, the CRCC has obviously evolved and extended its scope of research. In Paris, most of its premises now house specialists in a variety of fields, such as leather and parchment, photographs, plastic, natural history specimens, as well as issues regarding lighting and art display. In Champs-sur-Marne, east of Paris, the CRCC’s affiliated partner laboratory, the LRMH,2 deals mainly with stone, stained glass, concrete, and decorated caves.

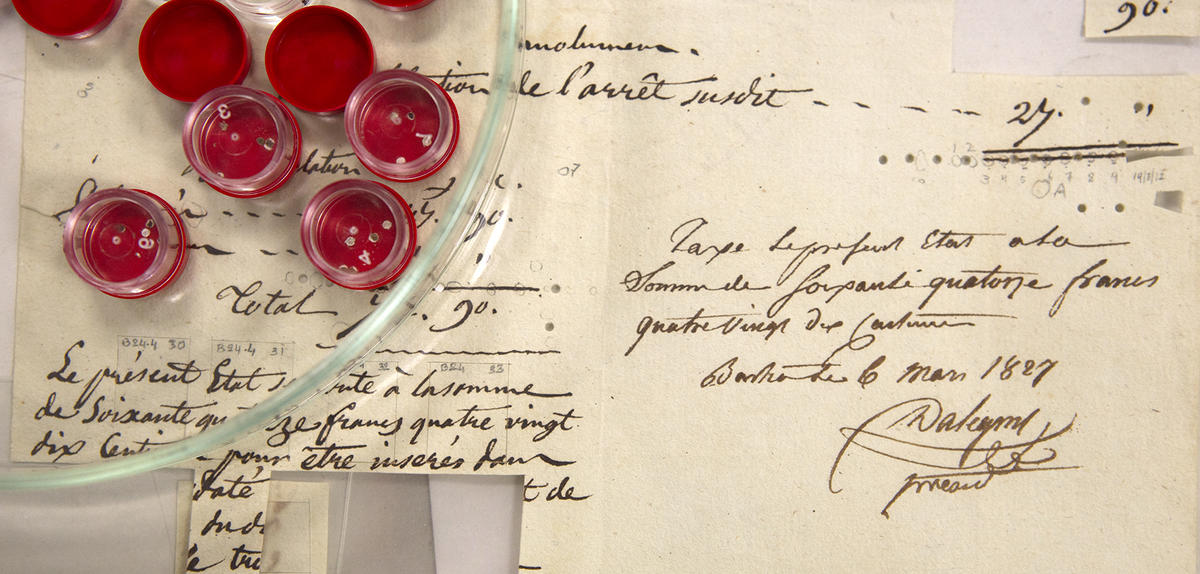

“The CRCC’s diversification has by no means been detrimental to its work on graphic documents,” stresses the center’s director Bertrand Lavérine. Indeed, microbiologist Malalanirina Rakotonirainy is happy to show off the laboratory’s carefully refrigerated fungus collection. With its 120 strains of molds and yeasts that regularly plague libraries, the collection is key to the consulting services provided by the researcher and her team to curators, who send samples for analysis. It is also used for advanced molecular biology research on stains such as the reddish-brown foxing that often affects old books.

Tides of time

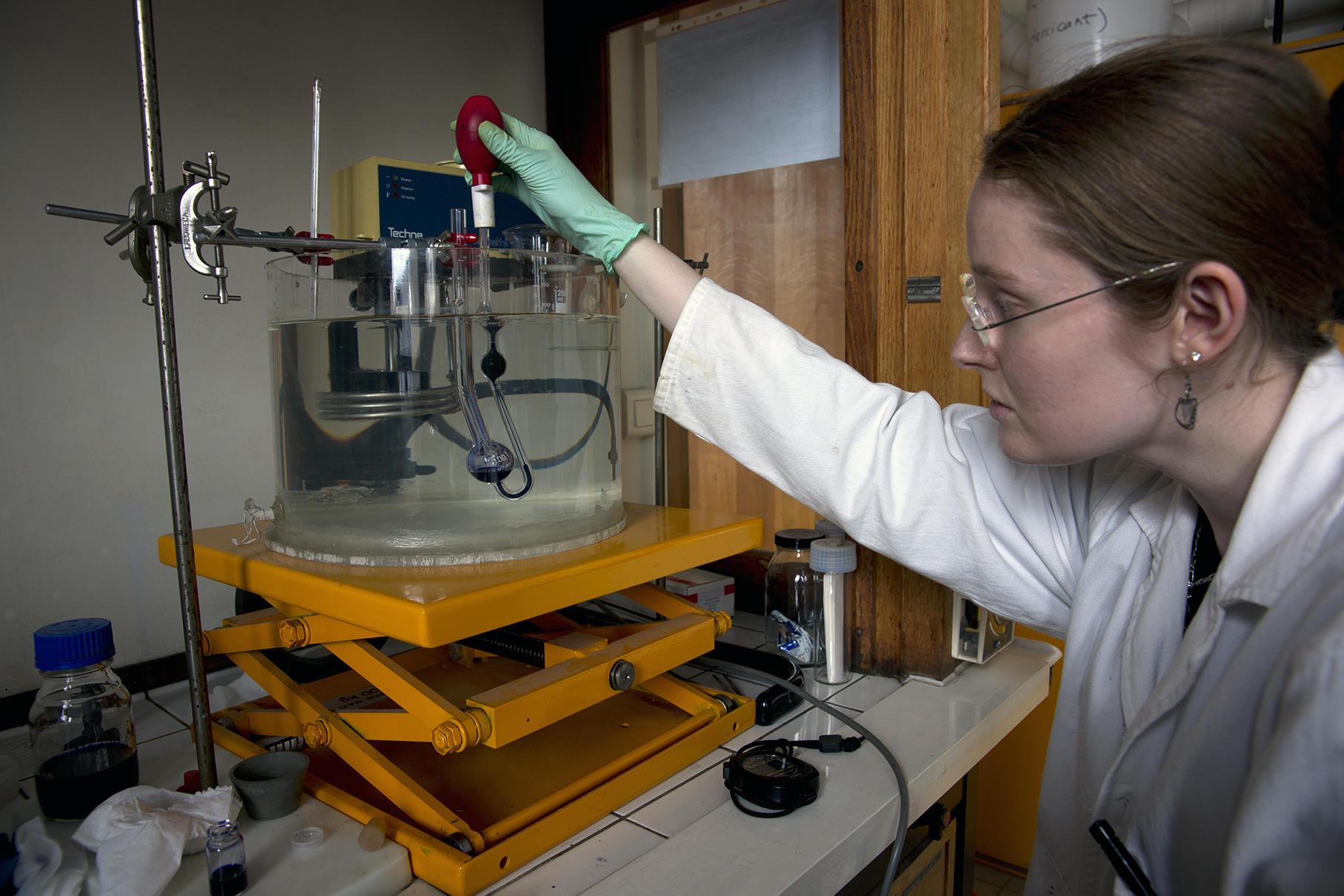

On the floor below, scientists are working on so-called “tide lines.” Researcher Anne-Laurence Dupont and her colleagues are involved in an extensive international program to study the brown lines that appear at the wet-dry interface when paper comes into contact with water. They are also investigating a new solvent-based process, which uses compounds called aminoalkyl alkoxysilanes, to strengthen papers significantly weakened by time-induced acidification. As an example, Dupont slides one such document out of a drawer—an old newspaper in a plastic sleeve, which would crumble if handled directly.

Newspapers are not the only treasures hidden in the conservation center’s cupboards. Researcher Véronique Rouchon remembers examining one of the oldest pieces of paper in the world, a 2000-year-old sample discovered by ArScAn3 researchers Jean-Paul Desroches, Guilhem André, and their team during a French archeological mission in Mongolia in 2006. It had been carefully preserved in a polystyrene box ever since.

A 10-year investigation

Rouchon and her colleagues also study iron gall ink. “In Western europe, from the Middle Ages to the 19th century, most writing was made with this type of ink. Containing ferrous sulfate, gum arabic, and oak galls, it poses a recurrent problem for librarians,” the scientist explains. “Over time, it diffuses through the paper, browns the back and damages the cellulose, creating splits and holes.” Once researchers had established that the iron(II) sulfate contained in the ink was the main culprit for this chemical degradation, they artificially reproduced the effect in order to determine the most effective treatment for severely damaged documents. This important study, which lasted approximately 10 years and was partly conducted at the SOLeIL synchrotron facility, south of Paris, enabled scientists to propose novel treatments that simply require contact with an interleaved sheet impregnated with active products, rather than complete immersion in a solution. This result perfectly reflects the CRCC’s mission of preserving the past through innovation.

This article originally appeared in CNRS International Magazine issue 28