You are here

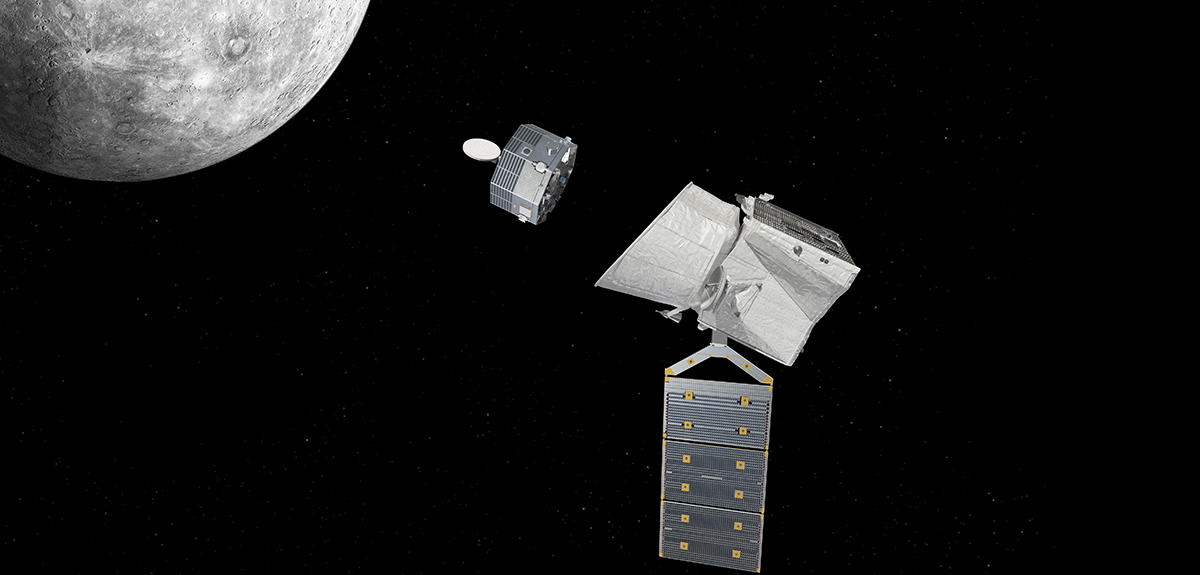

BepiColombo: Two Orbiters Head to Mercury

Apart from Earth, Mercury is the only terrestrial planet with its own magnetic field, and yet it has only been visited by two space missions so far. This is indeed no easy task: because it is so close to the Sun, a spacecraft that misses the Swift Planet's weak gravitational field will inevitably plunge towards the solar surface, heated to a fiery 5,500 °C.

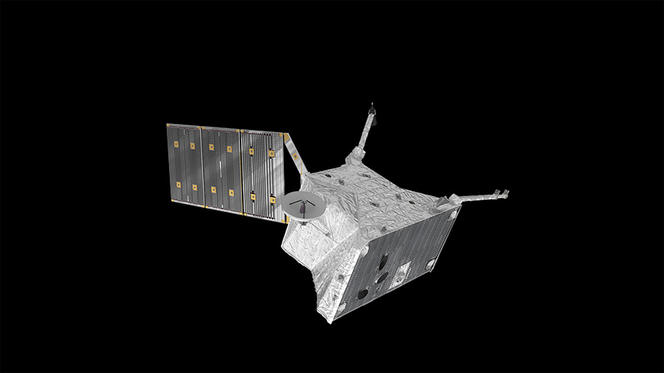

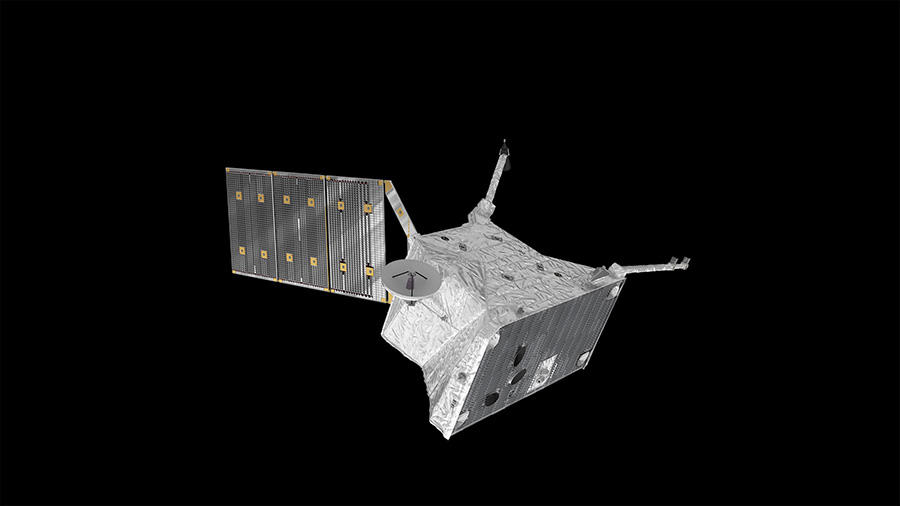

The European and Japanese space agencies, ESA and JAXA, have therefore worked in close collaboration to ensure BepiColombo’s success. The mission, which comprises two orbiters, is scheduled to launch from Kourou, French Guiana, on the night of 19-20 October aboard an Ariane 5 rocket. After a seven-year journey and two flybys of Venus to benefit from a gravity assist, it will then survey Mercury’s surface, atmosphere and magnetosphere for two years, until 2027.

From Mariner to Bepi

In the 1970s, during a mission mainly focused on Venus, the American spacecraft Mariner 10 carried out three flybys of Mercury. One of the researchers involved was a professor at the University of Padua, Italy, called Giuseppe “Bepi” Colombo. The new spacecraft, the very first collaboration between ESA and JAXA, was named after him.

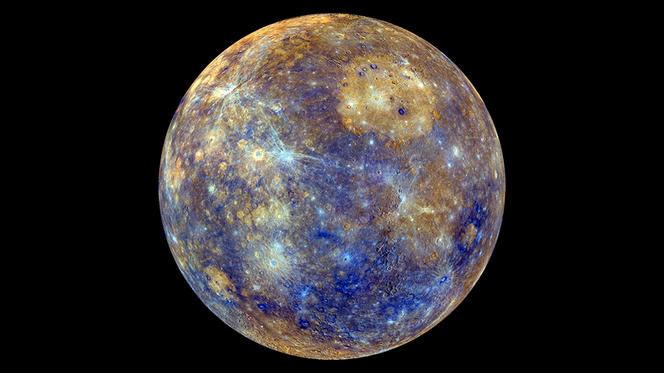

During the brief flybys, Mariner 10 was able to map half of Mercury and detect its magnetic field. Although it is much weaker than the Earth's, it shows that the core of the planet is still active. Mariner 10 also confirmed the presence of an exosphere, an extremely tenuous atmosphere extending to very high altitudes.

Many years later, NASA launched the Messenger1 spacecraft. Placed in orbit around Mercury in March 2011, it crashed onto its surface in April 2015 when it ran out of fuel. It confirmed Mariner 10's observations, and carried out further mapping and surveys of the surface. In particular, Messenger discovered evidence not only of volcanic activity and plate tectonics, but also of water ice: due to Mercury’s extremely small axial tilt, no direct sunlight ever reaches the bottom of impact craters at the poles.

“Although Messenger carried a magnetometer and equipment to measure ions and energetic particles, the spacecraft’s main mission was to survey the planet, its thin atmosphere and its surface," explains Dominique Delcourt, CNRS senior researcher and director of the LPC2E,2 in charge of the ion mass spectrometer on board BepiColombo’s Japanese-designed orbiter, MMO.3 "In the presence of an intrinsic magnetic field, a magnetic cavity forms in space. This is called the magnetosphere, where many particle transport and acceleration processes take place.”

One mission, two orbiters

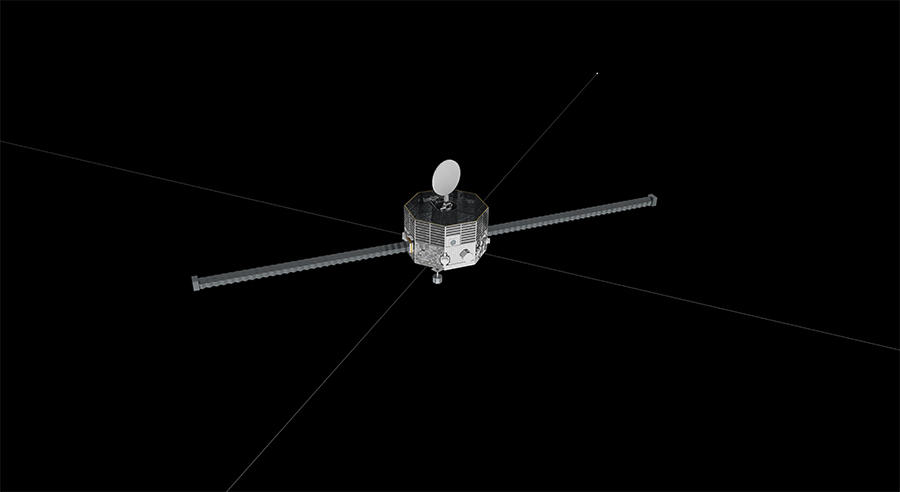

The BepiColombo mission comprises two orbiters carrying a science payload of nearly 100 kilograms. The first one, MPO (Bepi),4 will be dedicated to fully mapping the planet and studying its surface, internal structure and exosphere, while the second, MMO (renamed Mio), will study its magnetic environment. Once at their destination, Mio will be released first, followed by Bepi, which will be placed into the lowest orbit ever achieved around Mercury.

Delcourt is upbeat: “This wider array of instruments will enable us to not only make new discoveries, but also review Messenger’s data. By combining observations from both orbiters, we will also be in a position to perform what you might call stereoscopic measurements, something that was previously impossible.”

The MMO orbiter will complete one rotation in just four seconds, enabling its instruments to point in all directions in space in search of neutral or ionised particles and electromagnetic waves. With a higher resolution than the Messenger instrument, the MSA5 ion spectrometer, developed at the LPP6 in collaboration with Japanese and German teams, can distinguish between heavy atoms only one atomic mass unit apart, such as potassium and calcium.

“These measurements will enable us to characterise ejected planetary material," says Delcourt. “As a result of meteorite bombardment and the solar wind, matter is ejected from the surface of Mercury. It can then be ionised by the Sun's ultraviolet radiation, and transported and accelerated around the planet.” By studying these ions, it will be possible to analyse the composition of the surface without having to land on it.

A model magnetic field

The magnetic field of Mercury is also an interesting generic model. Observing a magnetosphere that is smaller than ours should improve our understanding of the behaviour of both neutral and ionised matter in space. At such a short distance from the Sun, the density of the solar wind means that it has a greater impact on the planet. Another interesting factor is that Mercury's highly elliptical orbit causes significant cyclical variations in this exposure.As a result, BepiColombo’s various scientific instruments are likely to be kept extremely busy. Six of them were designed with the participation of eight CNRS laboratories, including the LPC2E, the IAS,7 IPGP,8 the Research Institute in Astrophysics and Planetology (IRAP),9 the LAM,10 LATMOS,11 LESIA12 and LPP.

At the LATMOS, Éric Quemerais is the lead scientist for PHEBUS. This ultraviolet spectrometer scans frequencies ranging from 50 to 320 nanometers, as well as a few lines used to detect calcium and potassium.

Analysing Mercury’s surface

“We cover a wider spectral range that includes elements that were invisible to Messenger, such as helium, sulfur, ionised calcium, dihydrogen, etc.,” Quemerais explains. “Thanks to a better signal-to-noise ratio, we also have an improved detection limit.” And whereas the American spectrometer was aligned with its probe, PHEBUS has an independent pointing mechanism. This allows it to choose its direction, and provides better spatial and temporal coverage in orbit. “The exosphere gives an idea of the composition of Mercury’s surface and of its outermost layers," Quemerais adds. “For instance, we know that we will detect calcium and sodium, but we also expect to find magnesium, potassium and oxygen, whose presence has not yet been systematically confirmed.”

Another advantage of ultraviolet light is that it reflects off ice in a different way, which means that PHEBUS will be able to spot any water ice present. “This technique has already been employed on the Moon," says Quemerais. “We will use these changes in the amount of reflected light to map Mercury’s two poles.” Because of its specific orbit, selected so that it could survey the North Pole, Messenger was only able to map half the planet.

BepiColombo thus promises to provide the scientific community with a wealth of new data. In June 2020 in Orléans (central France), Delcourt will be organising the next important conference dedicated to the Swift Planet. “Of course, BepiColombo won’t have reached its destination by then, but we will nonetheless be able to make use of Messenger’s data,” he explains. No doubt the scientists at that time will have their sights set on Venus, which Bepi Colombo will be about to swing past, propelled on its way to Mercury, its final destination.

- 1. Mercury surface, space environment, geochemistry and ranging.

- 2. Laboratoire de Physique et Chimie de l’Environnement et de l’Espace (CNRS/CNES/Université d’Orléans).

- 3. Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter.

- 4. Mercury Planetary Orbiter.

- 5. Mass Spectrum Analyzer.

- 6. LPP (CNRS/École Polytechnique/Observatoire de Paris/Université Paris-Sud/Sorbonne Université).

- 7. Institut d'Astrophysique Spatiale (CNRS / Université Paris Sud 11).

- 8. Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris (CNRS / Université Sorbonne Paris Cité).

- 9. Institut de recherche en astrophysique et planétologie (CNRS Unit /University of Toulouse Paul-Sabatier).

- 10. Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille (CNRS / Aix-Marseille Université).

- 11. Laboratoire atmosphères, milieux, observations spatiales (CNRS / UPMC / UVSQ).

- 12. Laboratoire d’études spatiales et d’instrumentation en astrophysique (CNRS/Observatoire de Paris/Univ. Paris-Diderot/UPMC/Univ. Versailles-Saint-Quentin/Cnes).

Explore more

Author

A graduate from the School of Journalism in Lille, Martin Koppe has worked for a number of publications including Dossiers d’archéologie, Science et Vie Junior and La Recherche, as well the website Maxisciences.com. He also holds degrees in art history, archaeometry, and epistemology.