You are here

AI rates the beauty of tropical fish

What if our relationship to biodiversity also depended on the emotional bond that we have with it? In an effort to elucidate the correlation between the beauty of different species, perception and conservation, Nicolas Mouquet, an ecologist at the MARine Biodiversity, Exploitation et Conservation (MARBEC) laboratory,1 has been engaged for the past few years in a long-term study on the aesthetic value that we humans assign to various fish. An initial report published in 2018 attributed “beauty” scores to 140 species of coral reef fish, rating them from the least appealing to the best looking. It was based on a seemingly simple method: hundreds of volunteers were asked to look at pairs of photos showing two different fish and choose the one they found most attractive.

The “ugly” species are more numerous, older and more varied

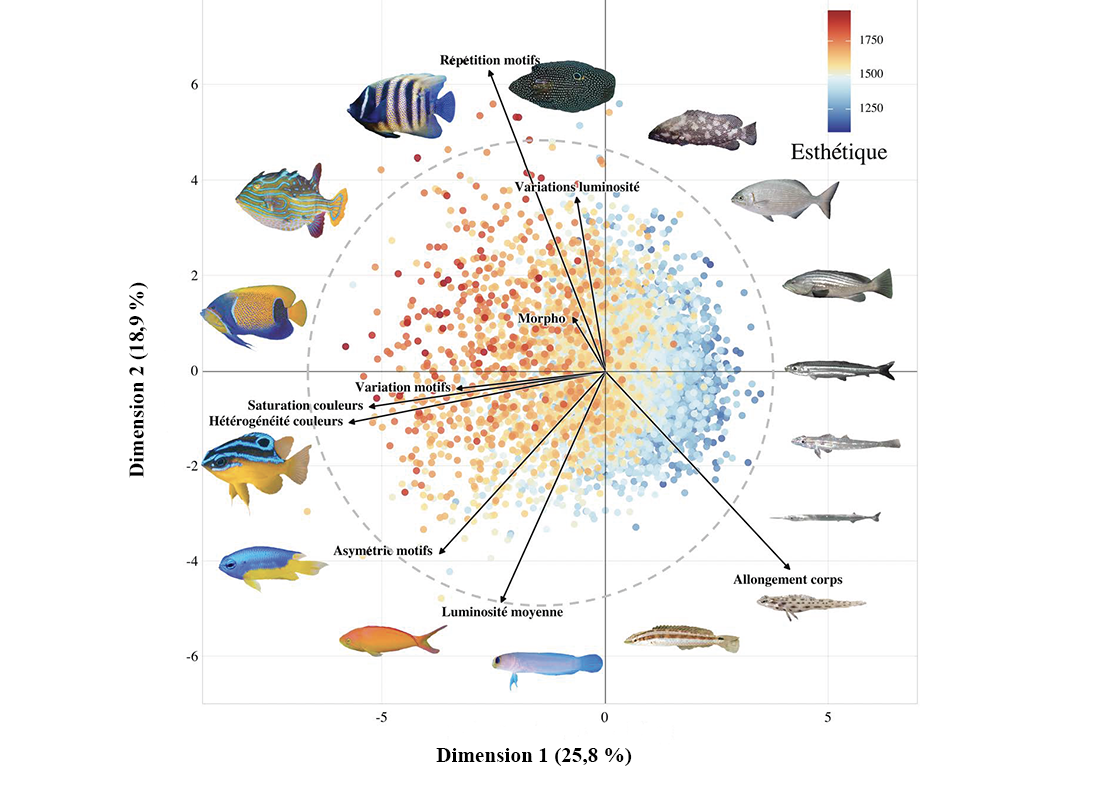

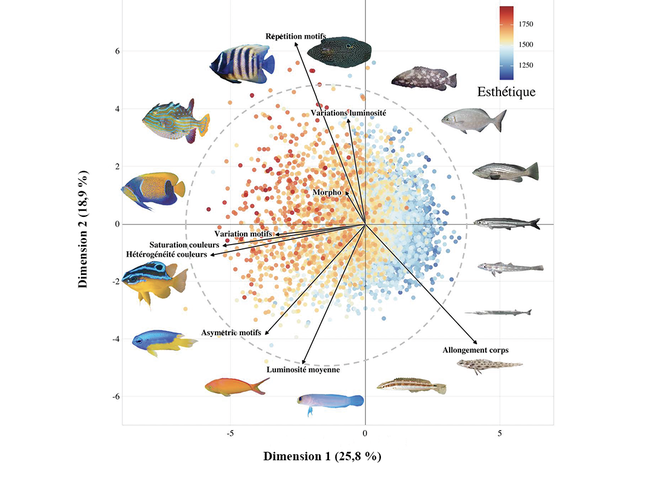

“We recorded a beauty score for each species and correlated it with each fish’s ecological characteristics – its size, whether it’s carnivorous or herbivorous, nocturnal or diurnal, in the middle or at the bottom of the water column, etc.,” Mouquet explains. The researchers then noted that the fish that are considered beautiful – those with sharp contrasts of luminosity (black/white) and colour (e.g. yellow/blue) as well as mostly rounded shapes, in other words visual signals that are easily decoded by the human brain – were in fact the species that had evolved quite recently (in the past 10 to 20 million years) in coral reefs, where their bright colours allow them to blend into their environment. In addition, they represent only a small branch of the tree of life.

The fish considered “less attractive” are by far the majority, with longer bodies, duller colours and less easily discernable patterns (for example, the bluish-grey fish found in the water column). The oldest of these species have been in existence for 100 million years and span a wider variety of ecological traits.

“There aren’t a hundred different ways to be beautiful, but there are certainly many to be ugly,” the researcher sums up. “Our biased perception causes us to find only a small fraction of coral reef fish species appealing. If this aesthetic filter influenced our conservation efforts, we wouldn’t be able to protect fully functional ecosystems.”

This initial study, which received a lot of attention in the media, nevertheless had its limits. It included a limited number of species and did not generate enough data to substantiate one of the researchers’ key hypotheses, namely that our perception bias – whether we consider some fish beautiful or not – could induce biases in our wildlife conservation policies. For this reason, the ecologists decided to use artificial intelligence (AI) and deep neural networks to expand the scope of their study from 140 to no fewer than 2,400 fish species.

“We used Reef Life Survey, an Australian database that keeps track of the fish populations of more than 1,800 marine sites worldwide – several thousand species in all. We selected 2,400 and compiled an image base of 4,800 photographs.” The researchers began by presenting 350 new photos to 11,000 volunteers around the world in order to generate data for their neural network, until the system was capable of predicting with a high degree of accuracy what humans would find appealing or ugly. The 2,400 selected species were then submitted for AI evaluation and rated for beauty – an enormous volume that would have been impossible to process by simple human means.

Researchers then linked the scores achieved by the fish to three lines of questioning. First, where do the different species appear on the phylogenetic tree that traces the evolutionary history of living beings? Secondly, is there a connection between their rating and the diversity of their ecological characteristics? And lastly, can a link be established between the results obtained and the conservation status of these species, as reported by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)?

An “ugly mug” prejudice that not even scientists can avoid?

Based on this vast volume of data, the biologists have shown that there is an evolutionary bottleneck in fish species: the families that have evolved more recently, like the well-known angelfish and butterflyfish, occupy only a tiny portion of the evolutionary tree. Ecological traits like diet, size, nocturnal vs. diurnal habits and position in the water column display greater diversity in the species deemed “less beautiful”.

Establishing a link with conservation status is more tricky, primarily because many coral reef fish are not assessed by the IUCN for lack of data. “Nonetheless, the list of endangered species comprises mostly those that are perceived as less beautiful, while the more attractive ones cause less concern,” Mouquet notes. “This can be explained above all by the use we make of different fish: many of the less visually appealing types are much sought-after by the fishing industry and therefore more at threat.”

Our aesthetic judgments seem to affect even the research work devoted to animal species in general, and fish species in particular. Indeed, it would seem that scientists are more likely to study those that they find beautiful or striking. This appearance-based prejudice against certain fish has yet to be confirmed and will be addressed in a new project: the research effort will be measured by counting the number of scientific papers published on each of the species concerned, in parallel with an evaluation of the general public’s interest in them through a survey of tweets and Google searches.

“It’s important to find out how our perception of a species conditions our behaviour towards it,” the ecologist emphasises. “If we have a better understanding of what we find attractive or endearing, it will help us define conservation actions that will be more acceptable to people, and thus more effective.” The researcher harbours another hope: that of changing the public’s view of species now considered less “desirable” in order to protect them better.

“Some of our biases are based on our attraction to bright colours, contrasts and rounded shapes,” Mouquet concludes. “But this judgment can be gradually altered by finding out more about the species, how they live and their role in the ecosystem. It’s just like contemporary art, in which it’s often necessary to learn about a work and its context in order to fully appreciate its beauty.”

- 1. CNRS / IRD / IFREMER / Université de Montpellier.