You are here

Bringing the Ancient Port of Rome Back to Life

Portus, the old port of Rome, was the largest maritime hub of the ancient Mediterranean world. Two thousand years ago it extended as far as the eye could see across the delta of the Tiber. But over the centuries it was gradually filled in and covered with sediment deposited by the river and the sea. Then the modern city of Fiumicino and Leonardo da Vinci International Airport were built on its ruins, preventing any archaeological excavation of the site.

Fortunately, however, through the magic of virtual reality, a team of geoarchaeologists and oceanographers has “unearthed” the giant harbor, reopening it to the circulation of water and sediments!1 “For the first time, the ancient port of Rome is back in virtual operation,” reports the Marseille-based oceanographer Bertrand Millet,2 co-author of the study. “This project has enabled us to solve a long-standing mystery about water circulation in the harbor.”

The size of… 275 football fields!

The construction of Portus, 32 kilometers to the west of Rome, was initiated by emperor Claudius in 42 AD, primarily as a landing stage for wheat from North Africa. The harbor stretched out over 200 hectares (the equivalent of 275 football fields!) and reached a record depth of 13 meters in places. In comparison, average-sized ports in those days spanned no more than half a hectare.

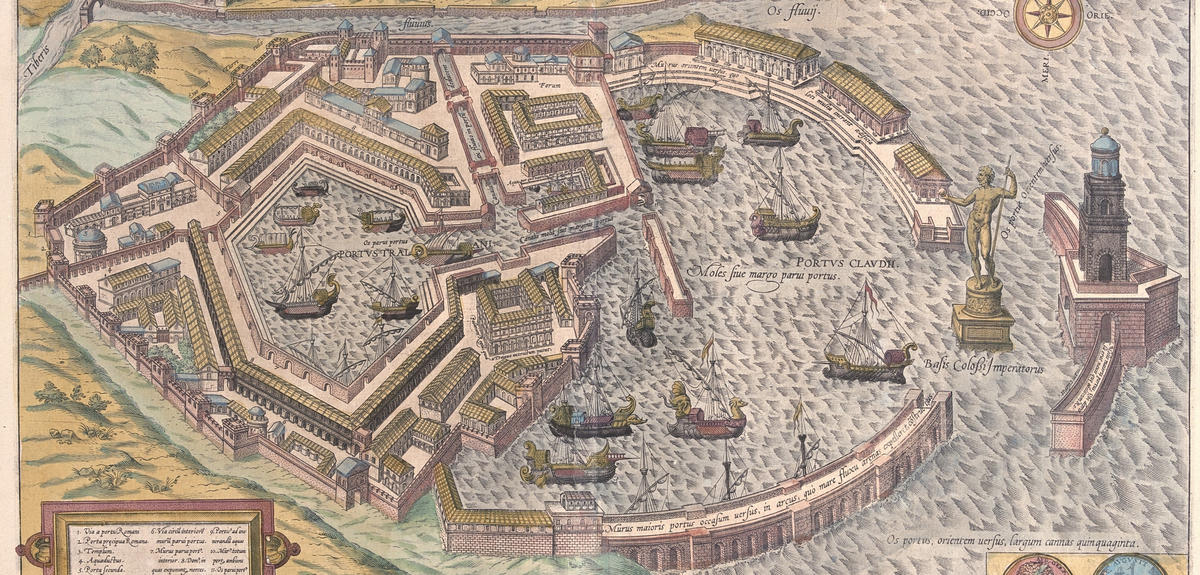

The overall structure of Portus has been known for over 400 years. This goes back to the Italian Renaissance cartographer Antonio Dante, who painted a first reconstruction as a large fresco in the Gallery of Maps of the Vatican. Yet until now, one question remained unanswered. The researchers did not know why the great Port had two entrances or passageways: a main entrance on the western side, through which ships entered and left, and another towards the north-east.

Au IIe s. ap. J.-C., Trajan fit constuire un bassin intérieur, de forme hexagonale, en creusant et en allongeant le canal de communication entre le port et le fleuve.

A hypothesis about the port had been proposed in 2010. A team led by the Lyon-based geoarchaeologist Jean-Philippe Goiran,3 who is also a co-author of this latest study, showed that Portus faced a major problem: the western part and especially the center of the harbor, where the ships had to pass to reach the wharves, tended to fill with silt. It was suggested that the northern channel had been built to help clear the waterways by creating a current through the harbor, which would stir up the sediment and carry it out to sea.

Digital technology to the rescue

To test this theory, the researchers launched a new study. The idea was to create a second channel north of the harbor and then close it (all virtually) in order to study its effect on the overall movement of water in the harbor.

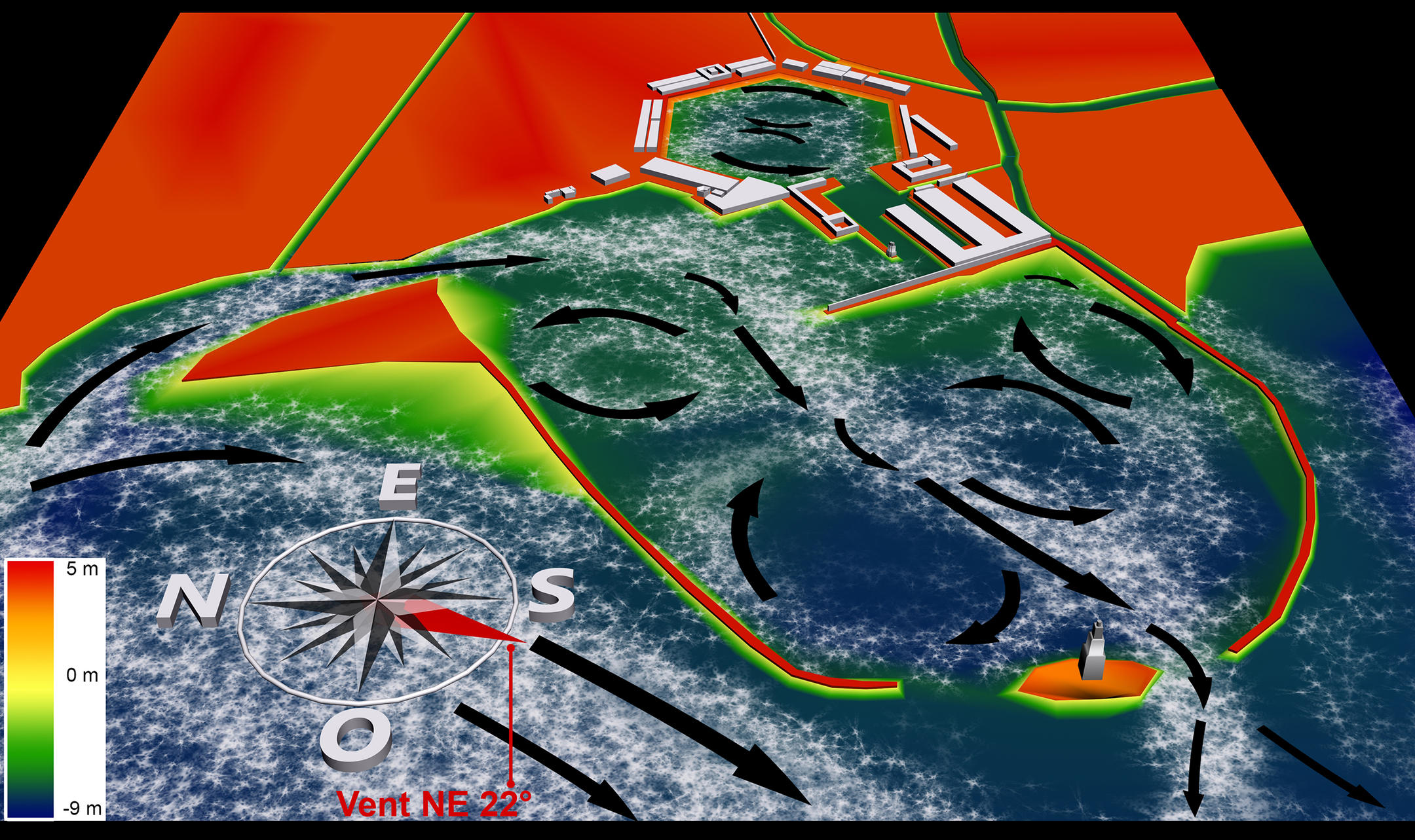

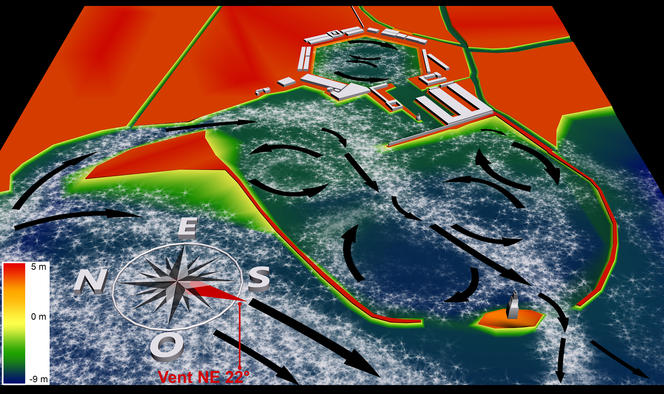

In practical terms, the team used a digital model that has proved effective over the past 30 years in research on many other ancient and modern-day harbors, including Marseille's Lacydon and the ancient port of Alexandria, in Egypt. “Our horizontal 2D model with vertical averaging calculates the moving speeds of different masses of water averaged over the entire water column. These movements are subject to certain influences, like wind speed and direction, or the opening or closing of a channel,” Millet explains.

A second entrance to clear the silt

In concrete terms, the model provided a 2D map of the port’s water circulation patterns, visualized by arrows indicating the directions and speeds of the currents. Then came the "eureka moment": it appeared that when the northern channel was opened, the 22° northeasterly winter wind induced a powerful circulation pattern across the entire harbor, strong enough to wash away the sediment that would build up in its central and western parts during the rest of the year. This confirms the hypothesis that the ancient Roman engineers had added the northern opening specifically to prevent the port from silting up too quickly.

Another important finding of the study is that, while it reduced the sedimentation, the northern channel did not stop it completely. Under the influence of the prevailing 247° southwesterly wind that blew over Portus in winter and summer, the circulation patterns continued to favor the build-up of silt throughout the western part of the harbor. This would explain why, despite the northern opening, the port of Rome was eventually filled with sediment—to the point that it finally disappeared completely…

- 1. B. Millet et al., “Hydrodynamic Modeling of the Roman Harbor of Portus in the Tiber Delta: The Impact of the North-Eastern Channel on Current and Sediment Dynamics,” Geoarchaeology, 2014. 29(5): 357-70.

- 2. Institut Méditerranéen d’Océanologie (CNRS / Aix-Marseille Université / Université de Toulon).

- 3. Laboratoire Archéorient de la MSH Maison de l’Orient et de la Méditerranée (CNRS / Université Lumière Lyon-II).

Explore more

Author

A freelance science journalist for ten years, Kheira Bettayeb specializes in the fields of medicine, biology, neuroscience, zoology, astronomy, physics and technology. She writes primarily for prominent national (France) magazines.