You are here

Shells, the Sentinels of the Ocean

Brest, at the Western tip of Brittany. Everything began in Finistère (Land’s End). From this end of the world jutting out into the Atlantic Ocean, researchers from the Laboratoire international associé Benthic Biodiversity Ecology, Sciences and Technologies (LIA BeBest)1 have been regularly exploring the world's seas, from Ouessant Island and Morocco to New Caledonia, Antarctica, and Mauritania. Their quest is a surprising one: they are searching for bivalve molluscs from the Pectinidae family, especially the famous great scallop (Pecten maximus) and their cousins, bay scallops.

Not out of a love of food, but from a thirst for knowledge, for over the last twenty years they have set out to discover these animals, and to show that they can serve as environmental archives: temperature and salinity, oxygen or contaminant levels, state of the phytoplankton in the natural environment..."Their external skeleton, which is to say their shell, records all kinds of ecological information that is helpful in understanding coastal ecosystems," explains Laurent Chauvaud, Senior Researcher at the Laboratoire des sciences de l’environnement marin2 and coordinator of BeBest, which grew out of this laboratory. On top of that, they provide quantities of very useful data for reconstructing past climate, and for following current warming as well as episodes of pollution. What's more, they can do so with an unprecedented level of detail, as today bivalves can inform us about the marine environment with greater temporal precision than the annual growth rings of a tree on Earth, or the layers of an ice core taken from the poles!

For example, Pecten maximus records the temperature of seawater on a daily basis to a precision of 0.5°C, like a medical thermometer. Better yet, researchers, including the young doctor Pierre Poitevin from the Université de Bretagne occidentale, have succeeded in giving voice to the sea scallop from the Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon archipelago in the Atlantic. Analysis of its shell provides detailed and precise information about its environment down to a quarter of an hour!

To reach this point, Chauvaud and his team learned over the years to decode the information archived by the shells. They observed and measured the distances between the fine striae or ridges present on the surface of the shells. And once beneath the binocular microscope, they continued to make discoveries: each distance separating these fine ridges is the result of the shell’s observed daily growth, and the decrease of these distances is connected to factors altering this growth, such as cooling seawater.

Mixed water and balanced diet

The demonstration of the impact of water temperature goes back to the year 2000, during a dive in Bergen, Norway. With lower levels of nitrates and other nutritive salts than bays in Brittany, this Nordic coast allowed them to establish, for the span of a summer's day, a correlation between slowdowns in growth and precise days of upwelling due to strong Northeast winds parallel to the coast.3

"On those days, Norwegian shells presented growth accidents," recalls the researcher. "As if paralysed by the cold water, they only grew the equivalent of one winter ridge during the middle of July! " A new approach was born, the study of great scallop ridges or striae.

Our Champollions of the ocean have discovered another factor that affects the distance between ridges: a sudden degradation in the mollusc's diet. In fact, when toxic algae blooms, as often happens in Brittany due to excess phytoplankton (as a result of nitrates from agricultural drainage), which is nevertheless the favourite food of the great scallop, their shell grows more slowly or even not at all. "You could love sauerkraut," Chauvaud explains, "but if the dish is so big that it prevents you from breathing, you might not want to eat anymore!"

Studying chemical composition

Yes, but how not to confuse these various indicators (in this case water temperature and diet) that are available to our scientists? "This is where sclerochemistry comes in," Chauvaud continues. "We are interested not just in the shell's structure, but also in its chemical composition."

The work of the biogeochemist and ecologist Julien Thébault, who is located in New Caledonia, made this advance possible. Researchers on site wanted to know whether nickel mining activity had contaminated one of the world's most beautiful lagoons, home to 25 species of pectinidae. Yet in comparing their data, they realized that traces of metals such as barium and molybdenum in the shells were correlated to phytoplankton blooms, excess phytoplankton, and sedimentation.

In 2005, they demonstrated that the calcite isotopes of shells gave precise daily information on water temperature after the fact, and that the presence of trace element (metallic) isotopes in the shells shed light on the dynamics of the environment. The scientific revolution is underway, making the great scallop and its congeners daily recording thermometers, and more generally indicators of the environment over time.

The researchers quickly became aware of the invaluable archives calling out to them, for these shells are abundantly present from Morocco to Norway, up to a depth of 500 meters, and dating back 25 million years! Enough to help them in their "investigations" of global warming as well as the history of the planet's ecosystems.

The clue that came from the cold

Still, the invaluable information provided by the great scallop is not enough to satisfy the thirst for knowledge of LIA BeBest’s researchers. The reason? Its short life span of four to five years. In the search for archives containing longer periods of time, which would help determine the impact of global changes such as today's warming, scientists prize long-lived bivalves: the fortysomething Laternula from Antarctica; the dog cockle Glycimeris glycimeris from Brest harbour, whose life span ranges from 70 to 80 years; the truncate soft-shell Mya truncata from the Arctic, the Astarte, or the northern propeller clam Cyrtodaria siliqua, all spry centenarians; and especially the black clam from Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, Arctica islandica, with a life span of 500 years! Widely distributed along the sandy bottom of the archipelago, the latter holds the longevity record for a non-colonial animal species, which is to say excluding corals.

"Arctica islandica is a genuine parchment!" says Chauvaud with excitement. "For a number of centuries, this immobile sediment-dwelling animal has filtered information within the calcium carbonate of its shell—at the rate of one ridge per year—helping to describe the environment of waters along the western front of the North Atlantic."

It is in fact this "clue" that researchers set out to Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon to explore. At the confluences of the Saint Lawrence River, the Labrador Current, and the Gulf Stream, the archipelago is experiencing one of the most intense current warmings. Using the biological information recorded by Arctica islandica in its shell year after year and ridge by ridge, scientists want to reconstruct the local climate during previous centuries, and thereby help develop a scenario for the century to come.

Survival in an extreme environment

And what of the poles? In Antarctica, researchers are interested in the circum-polar Antarctic scallop and its cousin, the soft shell clam. The environmental archives provided by these animals yield information on seasonal variations in ice, and hence on the impact of global warming. Beneath the pack ice, and deprived of light for five years before an ice breakup, phytoplankton algae has become rare near the scientific base of Dumont-d'Urville, and kelp algae is disappearing. But that is not true for bay scallops, despite the fact that their food is becoming scarcer!

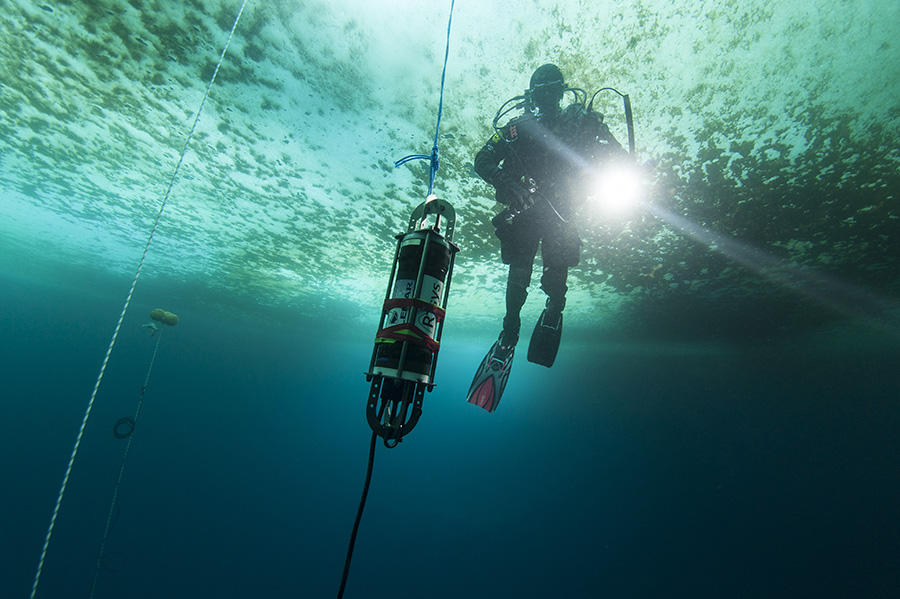

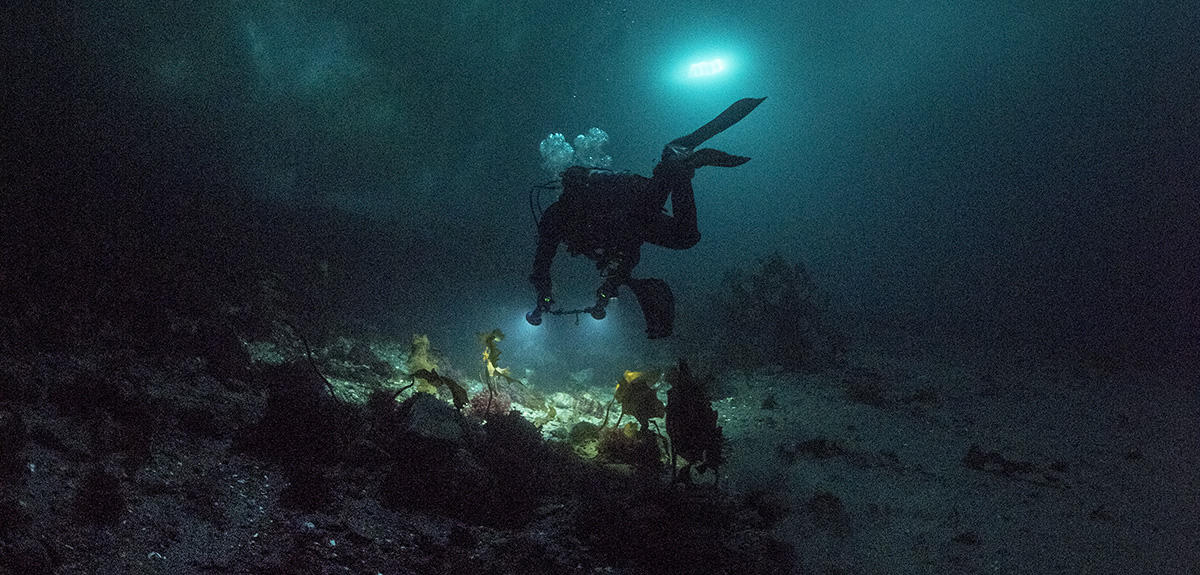

In order to examine them, the researcher-divers, who are not faint of heart, have developed—in conjunction with their Brest neighbour l'Institut polaire Paul-Émile-Victoran underwater polar research culture "made of ingenuity, failures, and a DIY spirit." They learned how to dig holes measuring 12 m2 in the ice pack in order to gain access to free water, cutting through a meter of snow and 3 meters of ice, before diving amid icebergs in water at a temperature of –1.8 ° C to take photographs or carry out precise procedures. "All this while wearing boxing gloves!" jokes Chauvaud.

While molluscs contain invaluable climactic data, they also have something to say about the pollution affecting their environment. That was actually the starting point of our scientists' research. In the early 1980s, faced with the increasing scarcity of great scallop populations, fishermen in Brest harbour alerted researchers at the Université de Bretagne occidentale and the Centre national d’exploitation des océans (Cnexo, the future Institut français de recherche pour l’exploitation de la mer, or Ifremer), in an effort to understand why this species had disappeared from an ecosystem that was nevertheless highly favourable at the outset. Researchers identified the causes: excess nitrate waste and toxic algae blooms.

Indicators of pollution

Since these initial steps, case studies have multiplied, often at the request of local professionals or officials. For instance, at Belle-Île-en-Mer in the Morbihan, scientists have studied shells that were alive during the early 21st century, in order to better understand the marine pollution after the sinking of the Erika oil tanker in December 1999. Sometimes chance also helps identify unexpected pollution. In 2018, Jean-Alix Barrat, a geologist specializing in micrometeorites, revealed a connection between the prescribing of MRIs to patients at Brest hospital, and the presence of the rare-earth metal gadolinium in the shells of great scallops in the harbour.

For Chauvaud there was no doubt, as molluscs and shells represent a scientific treasure that must be preserved, as demonstrated by what the researcher calls the "pecten library" sheltered in the cellars of the university. "Thirty years of great scallop shells are archived there, or so many reliable and daily indicators of growth, water temperature, and phytoplankton variation!" Their archiving could also open new avenues.

Jennifer Coston-Guarini is developing new mathematical models to study the link between shell shape and growth. "The shell is none other than passing time," observed the Scottish researcher D'Arcy Wenworth Thompson, who has established this notion as a fundamental law. Yet Coston-Guarini believes that he did not take the constraints of the environment into consideration, notably by omitting form, which also bears witness to the properties of the coastal environments in which the individuals grow. In other words, in addition to ridge distance and chemical composition, scientists could possibly soon deduce environmental information based on a mollusc's shape!

But that is not all, as they are also examining the behavioural modifications brought about by environmental stress, beginning with the movements of molluscs... Some of them are equipped with accelerometers similar to those in our mobile phones, cobbled together using Legos attached to the shell, which record the movements of bivalves at every moment. To "bother" them less, researchers came up with the idea of using hydrophones. Like paparazzi in search of indiscreet sounds, they seek to capture the underwater noises made by animal movements rather than the movements themselves. Today LIA BeBest divers are setting up their microphones to better observe marine life. They replay for visitors the strange song of lobsters, walruses, molluscs, and sea urchins...

The song of molluscs

This new approach has resonated with other fishermen, this time from the bay of Saint-Brieuc in the Côtes-d'Armor, where cocklers are worried: what impact will the Ailes Marines company's wind farm have on the resource? "The IIMPAIC program studies the complex acoustic effects of the beating of underwater stakes on the recruitment of larva in the water column," explains Frédéric Olivier, a researcher from the National Museum of Natural History within the laboratoire Biologie des organismes et écosystèmes aquatiques,4 which is associated with LIA BeBest.

To do so, this specialist in larval ecology installed a battery of loudspeakers at the Tinduff hatchery in Plougastel-Daoulas near Brest, before examining for potential growth delays in great scallop spats. The idea has attracted imitators, who now aim their hydrophones in many directions. "It will soon be possible to paint a marine sound landscape for Brest harbour," Chauvaud promises with a smile.

A little cramped in his office, whose luxury is a view of the houle de noroît (northwest wind) in the Brest bottleneck, LIA BeBest's youngest member, Youenn Jézéquel, does the spadework for wide swaths of passive acoustic research, prompting the respect of one of the pioneers in the subject, Jelle Atema from the American laboratory Woods Hole, where a friend of the group, Julien Bonnel, also works. Youenn Jézéquel sets his hydrophones to capture the low frequency sounds (100 Hz) emitted by lobsters, and passionately describes the stunning sound made by the snapping shrimp to stun its prey.

But for Chauvaud, the scientific work does not stop there. His mission is of course to transmit, but also to warn citizens of the changes and risks underway. Everything became clear during a polar dive, when he was stricken with fear. "Fear of the certainty of the catastrophe," he explains. How can a scientist, who is not accustomed to doing so, find the right words? How to overcome one's emotional discomfort, to recount one's astonishment before the enormity of climate change? Pleine mer, an exhibition organized by the agency Magnum Photos, provided an answer: "Everything I wanted to express was present before my eyes in a photograph by Jean Gaumy!"

Where gazes meet

It was a revelation for him: artists must take part in their scientific missions. Over the last seven years, LIA BeBest scientists have worked with the Fovearts company, which organizes the artistic direction and management of these residences, to bring to Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, Groenland, and Spitzberg the photographers Jean Gaumy and Benjamin Deroche, the artists Sandrine Paumelle and Emmanuelle Léonard, the video artist Jean-Pierre Aubé, or the writer Jean-Manuel Warnet. The latter wrote in his book Avant la débâcle (Before the Breakup)5: "We don't want to be snatched up by the icy water. So we raise our eyes to the immensity of the void. We swallow the light. The silence is blue." Chauvaud is certain: "Artists share the experience and humility of the scientists." This June in Brest, an exhibition will allow the public to discover this research thanks to the images, installations, and sound creations of these artists. And to change our point of view regarding these precious witnesses living along the world's coasts and ocean floor.

———————————————————————————————————

Arctic Blues : the Poles are on exhibit in Brest

At the heart of the exhibition circuit, the Ateliers des Capucins in Brest welcomes the Arctic Blues exhibition, built around missions to the poles made by the LIA BeBest team. The research conducted by the team of Laurent Chauvaud, Senior Researcher at the Laboratoire des sciences de l’environnement marin, will be presented in narrative from through works by artists who have been accompanying the researchers in the field for a number of years. Visitors can enjoy photographs by Jean Gaumy, Benjamin Deroche, and CNRS diver Erwan Amice, or video by Jean-Pierre Aubé. At the centre of the exhibition is a spectacular dome, which will immerse visitors in the visual and sound creations of three musicians, Maxime Dangles, Vincent Malassis, and François Joncour. This project was produced in collaboration with La Carène, Brest's venue for contemporary music. The CNRS is a partner of this event, curated by Emmanuelle Hascoët, along with the Ateliers des Capucins, Brest Métropole, and other institutions.

Click here for more information

- 1. The LIA BeBest brings together researchers from all disciplines with private companies and artists. Based on the collaboration between France’s CNRS and Quebec’s Ismer, along with their networks of partners, it is part of the l'Institut maritime France-Québec, with support from the CNRS and l'Université de Bretagne occidentale (UBO), pooling the research resources, know-how, and educational capacities of the Canadian (Ismer-Uqar, in Rimouski) and French (IUEM-UBO, Lemar, Brest) research groups.

- 2. CNRS/UBO/IRD/Ifremer.

- 3. This thermocline effect was studied and then modelized by the oceanographer and physicist Pascal Lazure, an Ifremer researcher at the Laboratoire d’océanographie physique et spatiale (CNRS/IRD/Université de Bretagne occidentale/ Ifremer), associated with BeBEST.

- 4. Borea (CNRS/MNHN/Sorbonne-Université/Université de Caen Normandie/IRD).

- 5. Avant la débâcle, Jean-Manuel Warnet, Éditions autonomes, 2018.

Explore more

Author

Working at the daily Ouest-France since 2003, Gaël Hautemulle is in charge of sea-related content for the Brest-based editorial office.