You are here

How Climatic Debt Chips Away at the Forests

Over the last 20 years, global warming has resulted in a temperature increase of 1°C in French forests. In order to survive, many animal and plant species must migrate northwards and to cooler summits in search of temperatures better suited to them.

Yet a number of recent studies have shown that the northward shift of animals and plants has lagged behind the rise in thermometer levels. This phenomenon is known as “climatic debt.”

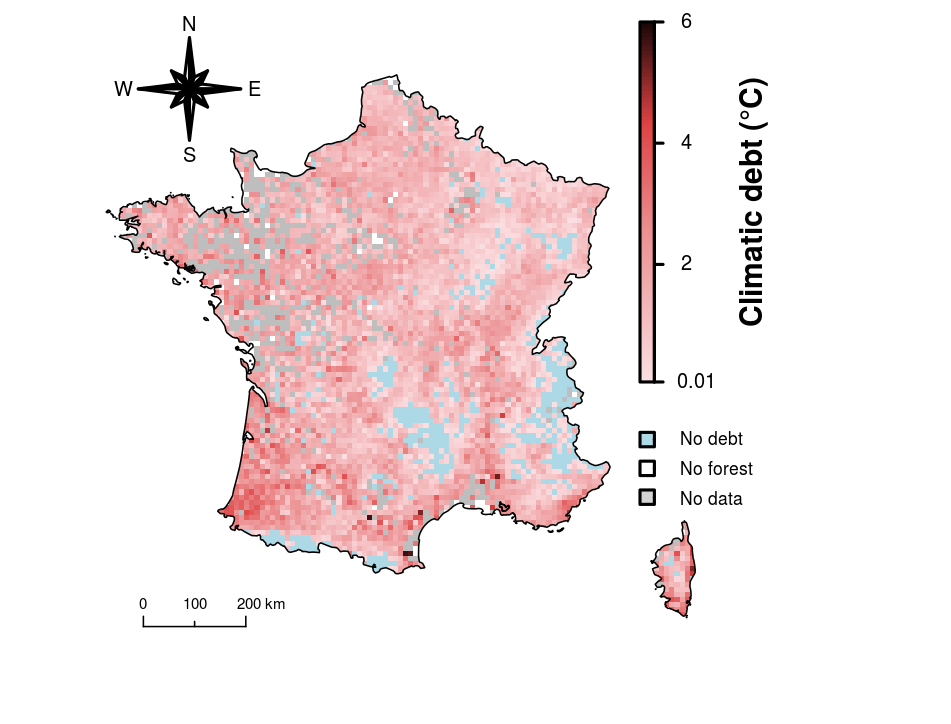

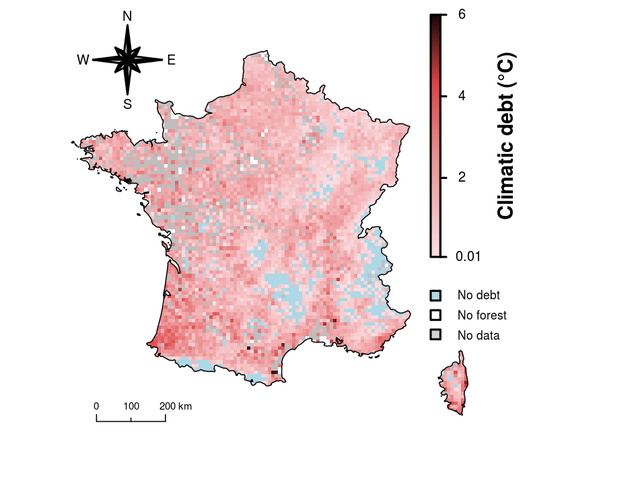

Thus, in a study published in 2011,1 Romain Bertrand2—who was then studying for his doctorate at AgroParisTech—and his colleagues observed that in the plains, communities of herbaceous forest plants (comprising several species of orchids and hyacinths for instance) were in fact adapted to temperatures 1°C cooler on average than the climatic conditions under which they were now growing. In other words, these plants did not immediately journey northwards as temperatures began to rise in their existing habitats.

Climatic debt: a threat to biodiversity

Ultimately, this climatic debt may lead to the extinction—local then global—of certain species unable to keep pace with the northward shift of climatic conditions favorable to them. Hence the importance of halting this phenomenon, or at least of slowing it down, and naturally, to this end, of elucidating the underlying processes.

In their most recent study, which has just been published in Nature Communications,3 Bertrand and his colleagues investigate the mechanisms responsible for climatic debt observed in French forests in 2011. Their exploration involved testing 23 ecological processes potentially affecting the response of different species to climate change (processes associated with both environmental constraints and the capacity of different species for resistance and migration).

The key factor responsible for climatic debt appears to be the existence in affected zones of already elevated temperatures, even before the advent of climate warming, for example in the forests around the Mediterranean.

“To reduce the climatic debt in these areas, there needs to be an immigration of species adapted to higher temperatures, from Spain or North Africa for example. However, such migration is restricted by geographical barriers (mountains, sea) and by the great distances between the forests in the south of France and those in warmer neighboring countries,” notes Bertrand.

Plants tend to resist temperature increase rather than migrate

The second major factor contributing to climatic debt is the ability of plants, hitherto underestimated, to cope with climate change, enabling them to survive in areas where unfavorable climatic conditions prevail.

It is essential to note that while several previous studies have suggested a rapid northward migration of species, the researchers observed a tendency among herbaceous forest plants to stay put rather than to migrate.

For the time being, this persistence is beneficial to vegetation, helping it resist warming, despite low levels of migration. “This is a very novel result and calls for more careful analysis of this capacity for resistance, which has not in fact been extensively studied before now,” adds the biologist.

However, this resistance may ultimately become highly problematic: the acceleration in warming forecast by 2100 (+1.6 to 4.9°C between 2091 and 2100 compared with +1°C over the last 20 years) means that such persistence may no longer be enough to offset the temperature increases. As a result, species currently remaining in situ, risk disappearing.

Which actions to slow down climatic debt?

The study also provides important preliminary results concerning the impact of human activities on climatic debt. In particular, it shows that certain practices may exert additional pressure on vegetation, thus exacerbating the phenomenon. Such actions include the creation of clearings in the forest canopy through tree-felling, but also increasing human attendance in forests.

“Cutting down trees results in reduced protection of the undergrowth from the Sun, which leads to higher temperatures; added to this humans, through travel and other activities, can also disturb the vegetation. All of these factors appear to affect the response of plants to the contemporary climate warming,” the researcher explains.

Although modern forest management takes into account the question of climate change, these findings signal a need for greater effort to minimize risks to the forest ecosystem.

Yet these are only preliminary suggestions, and clearly “the question of how to curb climatic debt requires further investigation.”

- 1. R. Bertrand et al., "Changes in plant community composition lag behind climate warming in lowland forests," Nature, 2011. 479: 517–520.

- 2. Centre de Théorisation et Modélisation de la Biodiversité, Station d'Ecologie Théorique et Expérimentale, Moulis (09); UMR5321 CNRS/Université Paul Sabatier Toulouse III.

- 3. R. Bertrand et al., "Ecological constraints increase the climatic debt in forests," Nature Communications, 2016. doi :10.1038/ ncomms12643

Click here for direct link.

Explore more

Author

A freelance science journalist for ten years, Kheira Bettayeb specializes in the fields of medicine, biology, neuroscience, zoology, astronomy, physics and technology. She writes primarily for prominent national (France) magazines.