You are here

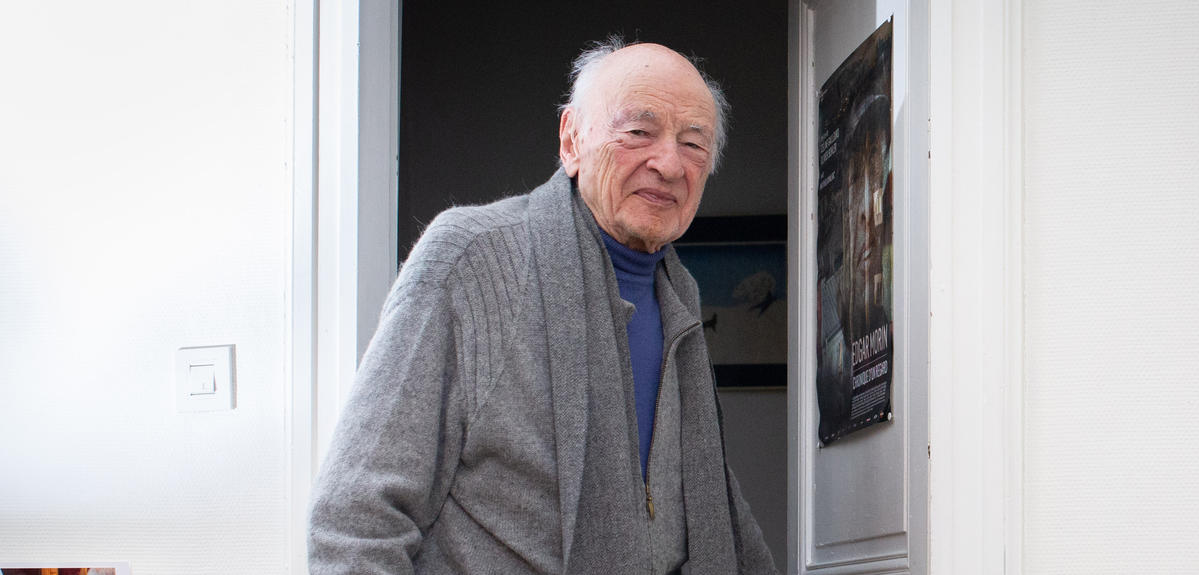

"Uncertainty is Intrinsic to the Human Condition"

The coronavirus pandemic has suddenly forced science into the spotlight. Will society be transformed as a result?

Edgar Morin: What strikes me is that much of the public has been thinking of science as a repository of absolute truths and irrefutable assertions. Everyone was reassured to see the President relying on a scientific advisory board. And yet what happened? People quickly realised that those scientists upheld very different or even contradictory points of view, whether on the measures to be taken, new possible remedies for dealing with the emergency, the suitability of a given medication, the timeframe of the clinical trials to be conducted… All of these controversies sow doubt in people’s minds.

Do you mean to say that the public might lose faith in science?

E.M.: No – not if people understand that controversy is what makes the sciences thrive and progress. The debates on chloroquine, for example, focused attention on the choice between urgency and caution. The scientific world had already seen fierce argument when AIDS first appeared in the 1980s. On the other hand, science philosophers have specifically shown us that dissension is an inherent part of research, which actually needs it to move forward. Unfortunately, few scientists have read Karl Popper, who established that a theory is scientific only if it is refutable. Nor are they familiar with Gaston Bachelard, who raised the problem of the complexity of knowledge, or Thomas Kuhn, who demonstrated how the history of the sciences is a discontinuous process. Too many researchers are unaware of the contributions of these great epistemologists and continue to work from a dogmatic perspective.

Could the nature of the current crisis alter this perception of science?

E.M.: I hope, although I cannot predict, that it will help reveal how science is much more complex than people want to believe, whether they see it as a catalogue of dogmas, or dismiss scientists as the modern equivalents of Diafoirus , always contradicting himself… Science is a human reality that, like democracy, is founded on the debating of ideas, although with more rigorous verification processes. Nonetheless, accepted theories have a tendency to become dogmatised, and the great innovators have always had trouble gaining recognition for their discoveries.

Consequently, the situation that we are experiencing today could be an opportunity to make the public, and researchers themselves, realise that scientific theories are not absolute, like religious dogma, but “biodegradable”.

The health disaster itself or the unprecedented confinement that we are living through: in your opinion, which is more significant?

E.M.: There is no reason to define a hierarchy between these two situations – they occurred in a chronological sequence, resulting in what we could call a crisis of civilisation, which forces us to change our behaviour and our lives on a local and global level. It all comes together in a complex whole. If we want to consider it from a philosophical point of view, we should try to find the connection among all such events and, above all, reflect on uncertainty, which is their primary characteristic.

What’s so interesting about the coronavirus epidemic is that the actual origin of the virus, its different forms, the populations it affects, and its level of harmfulness are little known… And we are also facing great unpredictability concerning its consequences in every sphere – social, economic, etc.

In your view, how do these uncertainties underpin all of these crises?

E.M.: This is because we must learn to accept them and live with them, even though our civilisation has instilled in us an increasing need for certainties about the future – often illusory and sometimes frivolous, when we’re told precisely what will happen to us in 2025! The emergence of this virus should remind us that uncertainty remains intrinsic to the human condition. All of the social insurance policies you may subscribe to can never guarantee that you won’t fall ill or that you’ll have a happy home life! We try to surround ourselves with as many guarantees as possible, but life is an ocean of uncertainty, upon which we sail between islands or archipelagos of convinctions, where we recharge …

What is your own rule of life?

E.M.: It’s more the result of my experience. I have seen so many unexpected events in my life – from the Soviet resistance in the early 1940s to the fall of the USSR, just to mention two historic events that seemed improbable before they actually happened – that it has become part of me. I do not live in constant anxiety, but I anticipate more or less catastrophic events will arise. I am not saying that I had foreseen today’s epidemic, but to give an example, I have been saying for years that with the degradation of our biosphere, we should be ready for disasters. “Expecting the unexpected” is part of my philosophy.

In addition, I am concerned about the fate of the world after realising, from reading Heidegger in 1960, that we are living in the planetary age, and then in 2000 that globalisation is a process that can cause as much harm as good. I have also observed that unbridled technical-economic development, driven by an insatiable thirst for profit and fostered by a global neo-liberal political climate, has become toxic, triggering all manner of crises. Ever since then, I have been intellectually prepared to face the unexpected, to tackle upheavals.

Looking at France, what do you think of the government’s management of the epidemic?

E.M.: It’s a shame that certain needs were refuted, like that of wearing a mask, just to “mask” the fact that there weren’t enough on hand! The government also said that tests were of no use, solely not to have to admit that there weren’t enough test kits either. It would be human to recognise that errors were made and will be corrected. Being responsible means acknowledging one’s mistakes. That said, I have noted that, starting from his first speech on the crisis, President Macron has not talked only about companies, but about employees and workers. That’s a first! Let’s hope that he will ultimately free himself from the financial world – he even evoked the possibility of changing the country’s development model…

Are we headed towards an economic change?

E.M.: Our system, based on competitiveness and profitability, often has serious consequences in terms of working conditions. The large-scale adoption of remote working made necessary by confinement could help change the operating methods of companies that are still overly hierarchical or authoritarian. The crisis could also accelerate a return to local production and the disappearance of the entire disposable products industry, providing work in the process for tradespeople and local businesses. At a time when the labour unions are considerably weakened, this type of collective action can contribute to improve working conditions.

Are we going through a political change, a transformation of relations between the individual and the community?

E.M.: Individual interest used to prevail over everything, but now solidarity is re-emerging. Look at the hospitals: the sector was roiled by deep-rooted dissensions and discontent, but in reaction to the influx of patients it has shown an extraordinary sense of cohesion. Even in confinement, the public has understood this, and applauds all the devoted, hard-working healthcare personnel every evening. This is unquestionably a point of progress, at least on a national scale. Unfortunately, we have not witnessed a resurgence of human or planetary solidarity, even though we all, across humanity, are already facing the global problems of environmental damage and economic cynicism. As we find ourselves confined today, all of us, from Nigeria to New Zealand, must realise that our destinies are intertwined whether we like it or not. This is the time for us to reconnect with our humanism. If we do not see humanity as a community with a shared destiny, we cannot exert pressure on our governments to take effective, innovative action.

As a philosopher, what can you teach us about how to endure these long periods of confinement?

E.M.: It’s true that for many of us who spend a large part of our time outside the home, this sudden lockdown can be an ordeal. I think it can also be an opportunity to take stock of our lives and identify what is frivolous or futile. I’m not saying that wisdom comes from spending one’s whole existence in confinement. But concerning our buying patterns or diet, this may be the moment to wean ourselves off mass consumption whose failings we know too well, the right time to “detox”. It is also a chance to develop a lasting awareness of the human truths that we all know but remain buried in our subconscious, and which are that love, friendship, fellowship and solidarity are what quality of life is all about.

Comments

Log in, join the CNRS News community