You are here

The Papuans, the Living Record of our Origins

“Over there, if you want to take the canoe out or wash in the river, you’d better do it in the middle of the day, because after 6:00 pm they come out. You can see dozens of pairs of eyes emerging from the water.” In this case, “over there” means in Papua New Guinea. And “they” refers to… crocodiles. In June and July 2019, François-Xavier Ricaut and his team from the EDB1 laboratory conducted two field missions to this far corner of the earth as part of the Papuan Past project.

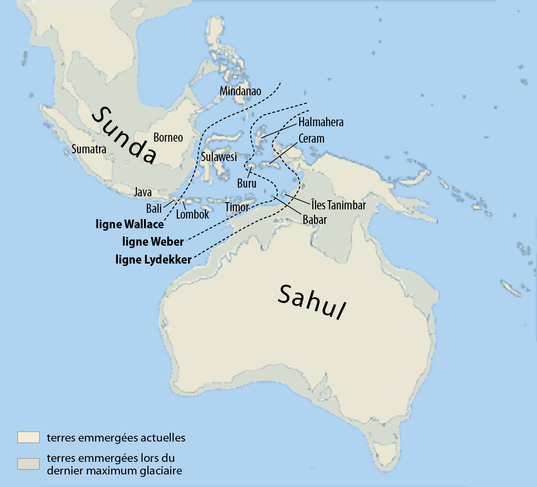

Their goal is to combine genetic and archaeological research in Papua New Guinea in order to plumb the secrets of a part of our ancestry, the earliest Homo sapiens to set foot in Melanesia, 65,000 to 50,000 years ago. The climate back then was very different from what it is now. The Earth had already been in an ice age for tens of thousands of years, and as a result the sea level was about 100 meters lower than today. At the time, the Indonesian islands were joined, forming a long strip of land jutting out from the rest of Asia, a formation that palaeogeographers call Sunda. Australia, Papua New Guinea and Tasmania were all one gigantic island, known as Sahul, which could be reached from Sunda only by crossing sea straits as wide as 100 kilometres.

Retracing the founding ancestors

“We want to know who these early ‘Sahulians’ (ancestors of the Papuans and Australian Aborigines) who landed in Sahul and gave rise to one of the world’s richest cultural and genetic diversities actually were,” the researcher explains. “We are especially interested in discovering the routes they took to populate Sahul, and in what period they arrived, in order to retrace modern man’s last exodus from Africa.” With Papuan Past, the scientists are striving to fit a new and central piece into the puzzle of the history of humanity.

And this can only be achieved through the Papuans. The direct descendants of the first Melanesian Homo sapiens, Papuans have conserved in their cells, more so than any other humans on the planet, the traces of mankind’s first journey to the edge of the world. Once they arrived at the end of their odyssey, these early Melanesians, with only a few exceptions, never left their remote land. Over the centuries, while other Sapiens in Asia and Europe were intermixing, blurring the traces of their migrations, the genome of the first Papuans, which is the same as that of the first Australian Aborigines, has remained essentially intact. With a unique genetic heritage incorporating 2 to 4% Neanderthal and 4 to 6% Denisovan genes, the Papuans are nothing less than the living record of our origins.

June 17. For one week the team has been working in the Middle Sepik region, a luxuriant marshy area of northwestern Papua New Guinea. The Indiana Joneses of science accompanying François-Xavier Ricaut include his colleague Sébastien Plutniak, as well as Matthew Leavesley and Reubenson Gegeu, both from the University of Papua New Guinea. “After travelling six hours by canoe on the Arafundi, a tributary of the great Sepik River,” the team leader recounts, “we walked to the village of Awim, guided by Sébi, our local contact. Even though it was the dry season, torrential rain had made our trek through the jungle extremely arduous. After a day of canoeing and hiking, we were welcomed in Awim to the rhythm of the ‘singsing’, a spectacular traditional dance!”2

For their investigation into the first Sahulian Homo sapiens, the team plans to decode the extraordinary, precious DNA of the Papuan people. The goal of these field missions is to take samples from the populations in different locations around the island, collecting the largest possible number of genomes. This genetic map should make it possible to identify a common denominator: the DNA record of the “founding ancestors.”

Genetic mutations and the molecular clock

To fulfil their mission, the researchers have a “secret weapon”: paleogenetics. Genetic information is handed down from one generation to the next, but not always in an identical form. At regular intervals, new elements called mutations appear and are transmitted to the descendants. The pacing of these mutations serves as a kind of clock, known as the molecular clock. By comparing the number of mutations between two sequences (sections) of DNA from two different individuals, researchers can determine when these individuals’ genomes diverged, thus identifying the period when their common ancestor lived.

“Today we have the technical means to analyse large numbers of genomes, which was impossible a few years ago,” François-Xavier Ricaut says. “By sequencing the DNA of a great many Papuans and Australian Aborigines, we can, in a sense, travel back in time.” Through their genetic database, the only one in the world for this region, the researchers have already succeeded in establishing a human settlement scenario. Their findings indicate that the first Homo sapiens set foot in Sahul 65,000 to 50,000 years ago. “This is consistent with the archaeology,” the scientist rejoyces. “Madjebebe in Australia and Ivane in Papua New Guinea, the two oldest known human settlement sites, are about 65,000 and 49,000 years old respectively. But this scenario of course needs to be verified.”

It is important to know the date of human settlement in Sahul in order to establish the origin of the Papuans and Australian Aborigines. Going even further, once the researchers know exactly when Sapiens arrived here, they can establish when modern man left Africa. “We think that the hominins migrated at a pace of one kilometre per year,” the anthropologist says. “If Sapiens arrived here between 65,000 and 50,000 years ago, this means that they left Africa between 75,000 and 60,000 years ago.”

Settlement and dispersion

The scientific adventurers are also in Papua New Guinea to answer a question posed by many palaeontologists in the world today: where did Sapiens first arrive in Sahul? They want to test two hypotheses: the first is that early man came from the north, via Sulawesi and the Bird’s Head Peninsula of New Guinea. The second hypothesis posits an arrival from the south, via Timor and the Australian continental shelf. And how did the populations disperse in Sahul? Via the central mountains or across the Arafura Plain (now submerged) to the south? (See map.) “Our first analyses suggest that the current populations of Papua New Guinea originate mostly from a settlement on the southeast side of the island,” François-Xavier Ricaut reports. To find out, the team collected samples from the populations of Daru in southern Papua New Guinea, on the shore of the Arafura Sea, across from Australia. Indeed, the genome of these men and women is very close to that of the “pioneer ancestors”. In order to confirm this scenario, new analyses are needed, which means more samples to be collected.

“After the introductions and usual ceremonies, the people were generally very enthusiastic about our work,” the scientist notes. “So much so that during this campaign we ran out of sampling equipment because there were so many volunteers! We collected the samples with as much transparency and human consideration as possible. In no way would we mistreat the Papuans ‘just’ for the sake of science. We want them to be a part of our research.”

For seven days, he and his fellow researchers roamed the Sepik region, hiking for hours through nearly impenetrable jungle and canoeing from village to village to collect DNA from a wide diversity of individuals and communities. “The more data we have, the more we can compare individuals and, using the molecular clock technique, trace the lineage back to the founding ancestors and identify their dispersion route. This diversity has already yielded some very precise information on the first Sapiens to reach Sahul’s shores. We think that they comprised at least six distinct genetic groups and about 1,500 individuals.”

These first Papuans and their descendants built an extraordinary complex of cultures. Over the millennia, some 800 different languages developed in New Guinea, accounting for 20% of all the languages spoken on the planet! This remarkable diversity no doubt arose from necessity. In this isolated part of the world, the families of the founding ancestors were faced with the risks of consanguinity. When the genetic heritage of a group is depleted, its people are more susceptible to illnesses and the community ultimately dies out. “We think that, in order to avoid inbreeding, the early Papuans organised themselves into small regional groups, distinguished by marked cultural differences,” François-Xavier Ricaut explains.

Archaeology to back up genetics

On 25 June, a change of scene. After a stopover in Port Moresby, the capital of Papua New Guinea, the team left the Sepik region and headed for Manim, a hamlet in the Highlands. Blanketed with dense tree fern forests, the mountains here rise to altitudes as high as 4,500 metres.

The goal of this second phase of the expedition was to confirm the genetic findings through archaeology. Here, among the hill villages, the researchers hoped to find other ancient settlements (besides Ivane and Madjebebe), which ideally would be located along the route that their genetic analyses seemed to indicate. “We set up our base camp near the Manim rock shelter, not far from the river of the same name, at an altitude of 1,770 metres in the Wurup Valley,” the anthropologist recounts. In this area, the local communities have planted gardens where they grow a large variety of local fruits and vegetables, including bananas, sugarcane, passion fruit, sweet potatoes, peanuts, taro, avocados… “This reminded us that Papua New Guinea is the world’s oldest agricultural/horticultural centre,” he adds. The Kuk site, a few kilometres from Manim, has been dated at 9,000 years old.

In addition to studying this shelter, the researchers scoured the Highlands looking for other settlement sites, with a view to gaining insight into the lifestyle of the first Melanesians. “Remnants of an impressive megafauna have been found in the strata of certain shelters,” the scientist goes on. “This leads us to think that when Sapiens arrived in Sahul, they encountered a whole population of giant endemic animals that they had never seen before: the diprotodon, zygomaturus, palorchestes… They must have thought that they had landed in another world! Furthermore, the Papuan oral tradition in certain regions is filled with stories of fantastic animals, probably inherited from the time of those pioneers.”

Examining the most recent strata in these ancient living places, the researchers found no further traces of this megafauna, no doubt because the animals had gradually become extinct in the millennia after the arrival of man, due to anthropic pressure (hunting, forest fires, etc.) as well as the climatic changes caused by ice age glaciation. “It is possible that, deprived of fauna, the early Melanesians turned more to plant resources,” the anthropologist Ricaut says. “At certain sites we’ve found traces of deforesting tools, and we have noted a change in the alimentary bolus, which came to consist mainly of vegetables. In fact, the vegetable-based cuisine that they invented back then is still an integral part of Papuan culture!”

The DNA speaks

July 4. Before returning to France, the researcher and his team paid a visit to the University of Melbourne in Australia. Some of the DNA samples collected in the field are being analysed at the Melbourne Integrative Genomics laboratory. The rest are under study at the University of Toulouse, which is equipped with the latest generation of DNA-sequencing equipment. “Thanks to the Papuans, we are gradually retracing the arrival of the first Sapiens in this remote part of the world,” the scientist says. “The next step is to determine more precisely their route, the number of individuals in the earliest pioneer groups, and the exact genetic heritage that they retained from the Denisovans, a species of hominins, discovered only in the past ten years, who populated the Earth at the same time as the Neanderthals and Sapiens. The first Melanesians interbred with them all along their way through Asia to Sahul, and also, as our most recent studies suggest, in Sahul itself.”

Still, many questions remain unanswered. “We know that the Papuans, descendants of these pioneers, have 4 to 6% Denisovan genes,” the researcher concludes. “But what exactly is the purpose of these genes? The initial data suggests that they give those who carry them a good immune response to illnesses and a particular ability to metabolise lipids. But do the Papuans carry other archaic genes that are useful, or even determinant? And have those genes been handed down to all of humanity?” The precious Papuan genome should soon provide the answers.