You are here

The Era of Automatic Control

Since 2014, France has been presiding the International Federation of Automatic Control (IFAC). Your laboratory, the LAAS, is organizing its 2017 Congress, which starts today. What exactly is automatic control?

Dimitri Peaucelle: Whereas automatons are devices, automatic control is a branch of scientific research that deals, amongst other things, with automatons. In our daily lives, we are surrounded by automated systems, such as refrigerators which maintain a constant temperature, battery chargers that adapt the charge to physicochemical state, cruise control mechanisms in cars, car braking systems (ABS), automatic pilots for aircraft and rockets, and so on. These dynamic systems require continuous control to ensure that the function in question is maintained: thus, a refrigerator motor switches on when the temperature rises above a certain level, cruise control increases the engine speed when a car travels uphill, etc. At all times, an algorithm known as a controller calculates the actions to be performed by various actuators (pumps, accelerators, etc.) to maintain the required function and prevent the system from either running out of control or stopping. Automatic control engineering is the science that designs these control algorithms, but also others for monitoring, diagnosis or estimation.

Are these automatic control systems present in all industrial sectors?

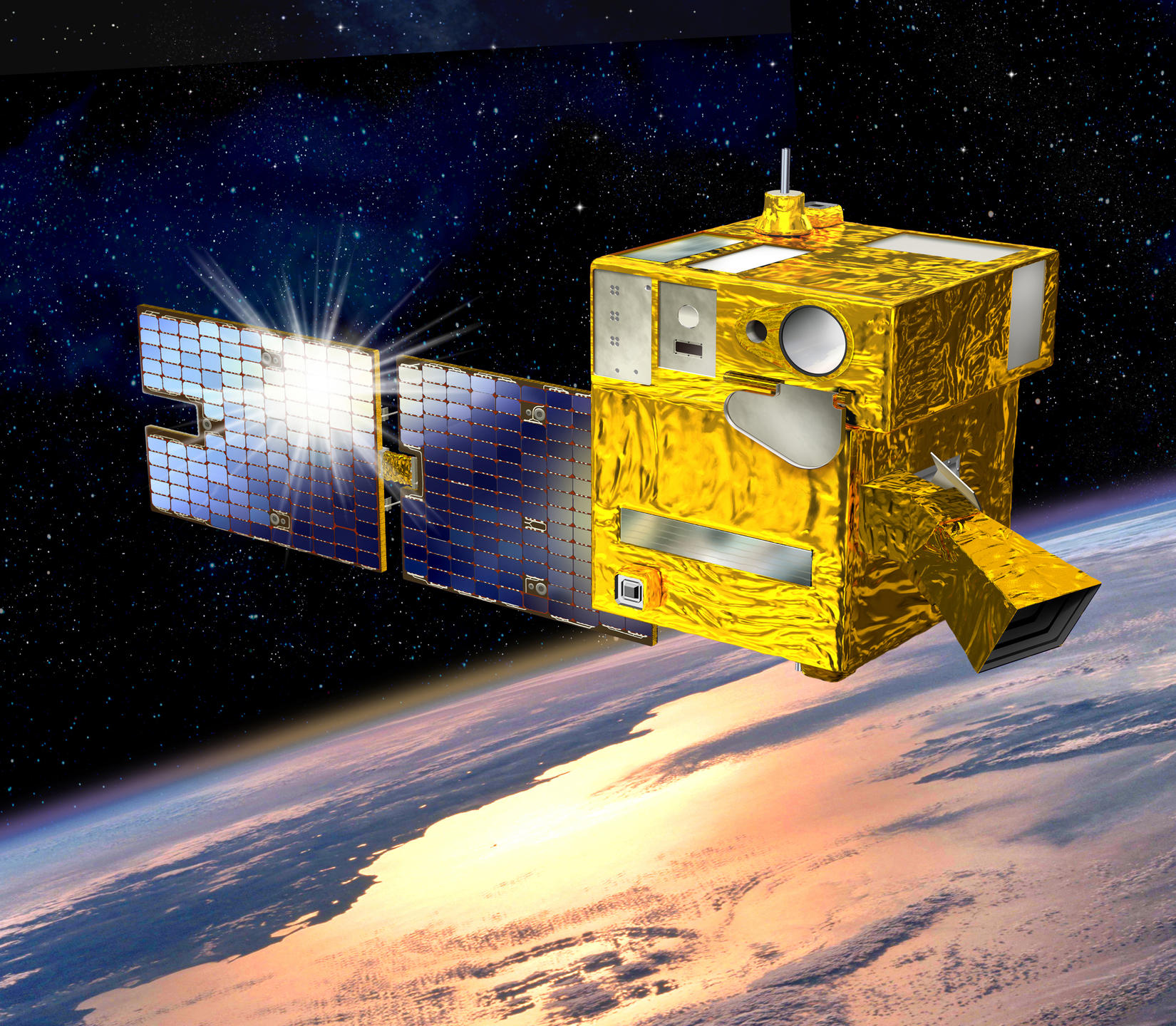

D. P.: Yes, automatic control engineers work in the fields of domestic appliances, automobiles, and aerospace, as well as in the regulation of chemical processes, wastewater management, 3D printers, and so on. Although the algorithms that control a refrigerator are straightforward, those used to maintain a satellite or rocket on path are extremely complex and require a great deal of expertise. Automatic control is a key sector for research and development of cutting-edge technology.

How long ago did automatic control originate?

D. P.: To create their water clocks, the Greeks already had to fully master the principle of feedback, a fundamental feature of automatic control. Yet this science really took off in the 19th century. With the rise of steam engines, it became necessary to develop mechanical regulators to avoid the machines running out of control and exploding. But the development of electronics in the 1940s and 50s enabled more complex regulators to be built. And today, with computers so powerful that they allow regulators to fit onto a microchip, the algorithms being developed by automatic control engineers are more sophisticated than they have ever been.

How does France, which is currently presiding the IFAC, fare in this field?

D. P.: For more than 10 years, France has been the country with the most presentations given at the IFAC and it is part of the leading pack of countries which, thanks to their full endorsement of cutting-edge technologies, have invested heavily in research on automatic control. The CNRS has contributed greatly to this phenomenon, and for many years has recruited high-caliber researchers, supported numerous international collaboration projects, and has chaired the Macs (Modelling, analysis and behavior of dynamic systems: Modélisation, analyse et conduite des systèmes dynamiques) research group.

You are an automatic control researcher at the LAAS. Which automatic control systems are you currently working on?

D. P.: For geographical reasons, we have very close ties with the aerospace sector. We are working with teams from Airbus Group responsible for designing aircrafts, launchers and satellites. In fact, I had the opportunity to supervise the PhD thesis of Alexandru Razvan Luzi, which culminated in the creation of a new control algorithm that was tested under real conditions on board the CNES Picard satellite in 2014.

Are these algorithms, thought up in the laboratory, tested before use?

D. P.: Of course! Many theoretical tests can be used to demonstrate that the requisite properties (maintenance of temperature, speed, trajectory, etc.) are guaranteed. It is only when such mathematical guarantees have been obtained that manufacturers are prepared to integrate these algorithms in their own systems and then carry out testing of their performance under real operating conditions.

What future problems will automatic control systems be able to overcome?

D. P.: We expect to be able to find a solution to the problem of controlling distributed systems. Today for instance, when numerous solar panels or wind turbines are connected to the network, it is very difficult to distribute the resulting electricity in accordance with consumer requirements. In some cases, more energy is consumed in distributing this electricity than in producing it. Consequently, automatic control engineers are working on algorithms that adapt distribution to power source fluctuations (wind, solar energy, etc.) and to consumption. In robotics, automatic control will also allow us to devise behavioral settings for individual devices so that a group of robots can collaborate in optimal fashion to accomplish a given task.

What are the most noteworthy features of the 2017 Congress?

2017 marks the 60th anniversary of the federation, which was founded in 1957 in Paris. It is an ideal opportunity to celebrate the Story of the IFAC and of Automatic Control in general, and to foresee the future. The world congress in Toulouse features panel sessions on both the history and on the up-and-coming achievements in industry, in education as well as for social systems. It will also invite—for the first time at the IFAC—the academic researchers and industrial engineers to present their work in a new “demonstrator” format. Prototypes, concrete applications and education-oriented devices will be showcased and tested at special sessions. Among these a session dedicated to automotive control will be held on Wednesday 12 and Thursday 13 July with special demonstration cars. But the anniversary is also the opportunity for celebrations. The July 13th Gala Dinner promises to be a unique festive event that we hope will be long remembered.