You are here

In the Middle of a Shark Feeding Frenzy

In June of each year, the southern channel of Fakarava Atoll in the Tuamotu Archipelago of French Polynesia hosts one of the densest populations of sharks in the world. Hundreds of grey reef sharks, a species often found around coral reefs, converge here for a gory feast: when the moon is full, thousands of groupers come to the channel to spawn, making easy prey for the predators. “While studying this unique aggregation of groupers, which numbers 18,000 at its peak and disperses immediately afterwards, we noted that they attract an impressive number of sharks,” explains Johann Mourier, a marine biologist at CRIOBE.1 In 2014, while filming a documentary entitled Le Mystère Mérou (The Grouper Mystery) with the diver and photographer Laurent Ballesta,2 Mourier was able to estimate the number of sharks—nearly 700 of them crowd into a channel barely one kilometer long—and tag some of them.

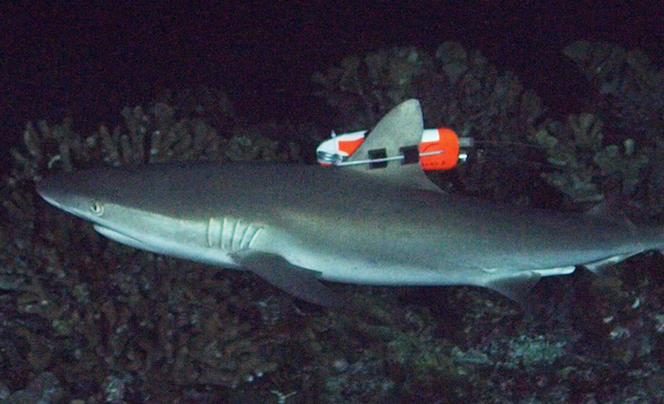

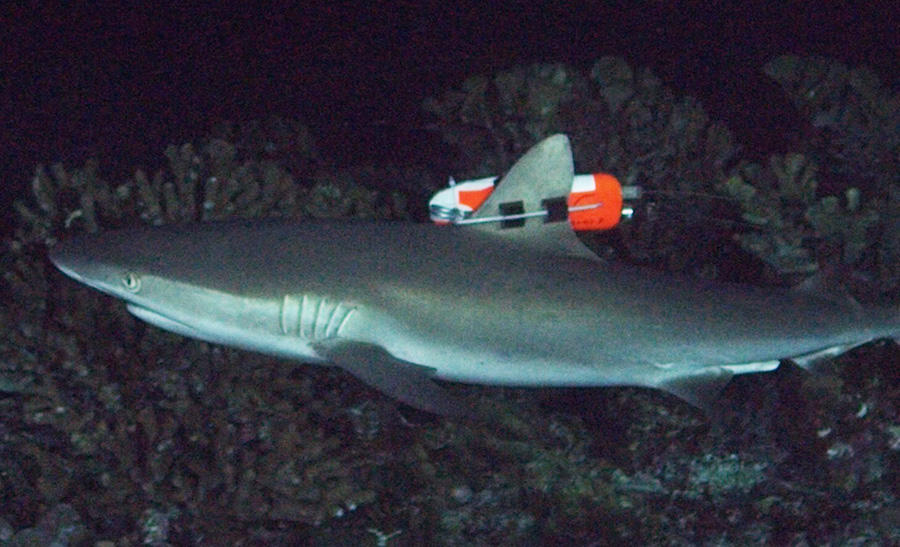

Eager to study this population, he returned in 2017 with an ambitious plan: to line the bottom of the channel with acoustic receivers, 25 in all, and to equip 40 sharks with acoustic transmitters combined with accelerometers, allowing him to closely monitor their movements and actions: their location in the channel, any social affinities they might demonstrate, and the timing of their feeding and resting periods. The ocean makes an excellent medium for sound waves — unlike GPS waves, which cannot travel through water.

The project took on greater scope when Ballesta and his team decided to film a new documentary, this time specifically about the grey reef sharks. But just tagging these animals, which grow to lengths of nearly two meters, was not enough. The researcher and photographer wanted to dive as close as they could to the “pack” and film them as they hunt, by day, but also at night. For Mourier it was a golden opportunity: “I couldn’t turn down the chance to make a documentary like this (called 700 sharks at night),” he says. “It’s a unique opportunity to share my research with the general public, but also to access scientific material — in this case, hours and hours of video — that I would otherwise never have.”

There are some 500 species of sharks in the world, one-third of which are endangered, and yet we know very little about these animals. Their social organization remains a mystery, and there is scant documentation about how they live and what they eat in their natural environment. “Sharks don’t have the opportunity to eat every day,” Mourier explains, “and the ones we catch often have empty stomachs. In addition, they regularly purge their systems by regurgitating the entire contents of their stomachs, which further reduces the possibilities for analyzing their diets.”

Fifty dives were organized in June and July 2017, yielding more than 300 hours of video. “At first we stayed above the sharks, keeping a certain distance,” Mourier recounts. “But as we did more dives, we realized that the sharks didn’t seem to notice out presence—or rather, that they took it into account in their movements. So we gradually dove lower, until we found ourselves right in the middle of the pack.” The resulting video sequences, which are unlike anything previously seen, reveal little-known aspects of the lives of grey reef sharks.

Fakarava’s southern channel has a mild current that enables the development of an entire ecosystem, including coral, fish and mollusks, offering an ideal habitat for grey sharks. “They rest during the day, floating in a ‘wall of sharks,’ all facing the same direction, with their heads into the current,” Mourier reports. Sharks can never stop swimming completely: they have negative buoyancy and their gills cannot function without movement—a motionless shark would simply stop breathing and sink to the bottom. By attaching cameras to a half-dozen sharks (the devices are temporary attached to a fin and detach automatically after 48 hours), the researchers were able to capture extraordinary point-of-view scenes from the daily lives of sharks. For example, some of them would dive to the bottom of the channel and allow the small cleaner fish there (wrasse) to pick out the parasites between their teeth.

After sundown, the sharks emerge from their torpor and start hunting. As Mourier explains, “Fish are less alert at night. Sharks are poor hunters and prefer to stalk their prey at night, reaching a peak of activity during a full moon and a bright sky. From our nighttime dives, we learned that the grey reef sharks of Fakarava hunt in packs—which came as a real surprise, because scientists had previously thought that sharks were not highly social animals.” Furthermore, the information supplied by the cameras and acoustic receivers shows that their seemingly chaotic “frenzy” is actually quite organized. “Every night, the sharks arrange themselves in huge spirals and attack every fish that swims by,” the biologist says. “If the prey escapes a first pair of jaws, and then a second or even a third, there is little chance that the next shark will miss it.”

Even more tellingly, the transmitters implanted in the abdomens of certain sharks, whose positions are represented by colored dots on the animated map of the channel, show that the animals form “teams” of two or three, staying near each other during the entire hunting period between 6:00 pm and midnight. “These duos and trios are more of an opportunistic relationship than an actual cooperation,” Mourier emphasizes. “One of the sharks might act as a ‘beater,’ stirring up the prey, but there is no sharing of the prize, as can be observed in other predators, like wolves, for example. Whichever shark manages to grab ahold of a fish devours it whole. But it’s still a genuine social interaction, indicating that the shark is a much more evolved animal than we had wanted to admit until now.”

Mourier has just begun to analyze the mass of data collected on site, but the images have already allowed him to identify an impressive number of possible food sources for the grey reef shark: it feeds on some 50 different species of fish and mollusks! “This is the first study to yield an exhaustive view of a shark’s diet in its natural environment,” the researcher adds. Moreover, with the “bullet time shot,”FermerThis cinematic special effect, famously used in the fight scenes of the Matrix movies, makes it possible to film a scene from every angle simultaneously using dozens of cameras — 32 in this case, spaced out on an arch four meters in diameter. a cinematic special effect that has never before been used in a marine documentary, Mourier can freeze a specific moment in the hunt and view it from any angle: “It allows us to see the action clearly, even in the middle of a mass of sharks, where it is sometimes hard to tell which one is doing what.”

Although the aggregation of groupers during the full moon in June is an especially active feeding time for the sharks, whose population peaks during this period, the Fakarava channel is also a mass spawning ground for many other species (surgeonfish, parrotfish, etc.), offering the sharks a regularly replenished larder. “This veritable home delivery service no doubt explains their sedentary habits,” Mourier suggests. “Of the 38 individuals that we equipped with transmitters, only two had left the channel six months later.”

The researcher has already drawn one major conclusion: “It is essential that we protect the sharks and ban shark fishing, as has been the case in Polynesia since 2011, but our initial findings show that this is not enough. For the sharks to survive, the entire ecosystem must be preserved.” Unlike Fakarava, which has been miraculously spared by the ravages of human activity and fishing, most of the other Polynesian atolls have lost their major spawning aggregations a long time ago… and the accompanying spectacular gatherings of sharks.

_______________________________________________________

Sharks tagged under hypnosis

Implanting a sound wave transmitter in the abdomen of a shark weighing 25 kilos and measuring more than 1.5 meters snout to tail is no easy task, especially in Fakarava, where shark fishing and even the use of fishhooks are banned. The divers therefore had to rely on ingenuity. “If you turn a shark over on its back, it immediately enters a state of tonic immobility, a kind of trance during which it doesn’t move,” Mourier explains. “Laurent Ballesta had the idea of catching the grey reef sharks underwater with a lasso so we could flip them over and pull them to the side of the boat in that position.” After a bit of practice, this rather athletic tagging technique proved effective, and also allowed the researchers to attach the above-mentioned cameras to the sharks’ fins.