You are here

Hegra’s Splendor Revealed

In April, France signed an agreement with Saudi Arabia for the tourism and cultural development of the Al-Ula region in the northwest of the kingdom. As an archaeologist, what do you think of this partnership?

Laïla Nehmé:1 I am delighted that the Saudi authorities have chosen France, which has an excellent reputation with regard to the management of nature reserves, museography, hotel infrastructure and so on, to develop this region. With an area of 22,000 km2, Al-Ula abounds in desert and mountain landscapes, palm groves and canyons suitable for trekking or horse riding, and is home to a flagship archaeological site, Madâ'in Sâlih (ancient Hegra, the little sister of Petra in Jordan), included in UNESCO's World Heritage List in July 2008.

Have there been similar partnerships between Saudi Arabia and France in the past?

L. N.: When it comes to archaeology, the two countries have a long tradition of trust, friendship and scientific cooperation. The first true explorers of the region, in the early twentiethth century, were Antonin Jaussen and Raphaël Savignac, two Dominican priests from the French Biblical and Archaeological School of Jerusalem. The descriptions of Madâ'in Sâlih they published in Mission Archéologique en Arabie (‘Archaeological Mission in Arabia’) remained the most comprehensive ever made until the work that I have been co-leading in the field since 2002, which is the first foreign archaeological mission authorised in Saudi Arabia since the 1970s.

Did the excavations allow you to identify how long the site had been occupied?

L. N.: Yes. Hegra was occupied roughly from the fifth century BC to the fifth century AD, although graves dating from the Bronze Age (at around the beginning of the second millennium BC) have been discovered there—yet without any traces of an associated settlement. The site, which covers more than 1 000 hectares, was inhabited by the Nabataeans mainly between the first century BC and the beginning of the second century AD. These wealthy merchants largely controlled the long-distance caravan trade of incense, myrrh and spices, which were transported by camel from Arabia Felix (‘Fertile Arabia’, now Yemen) to Mediterranean ports such as Gaza, before being shipped to Greece and Rome.

Which regions were occupied by the Nabataeans?

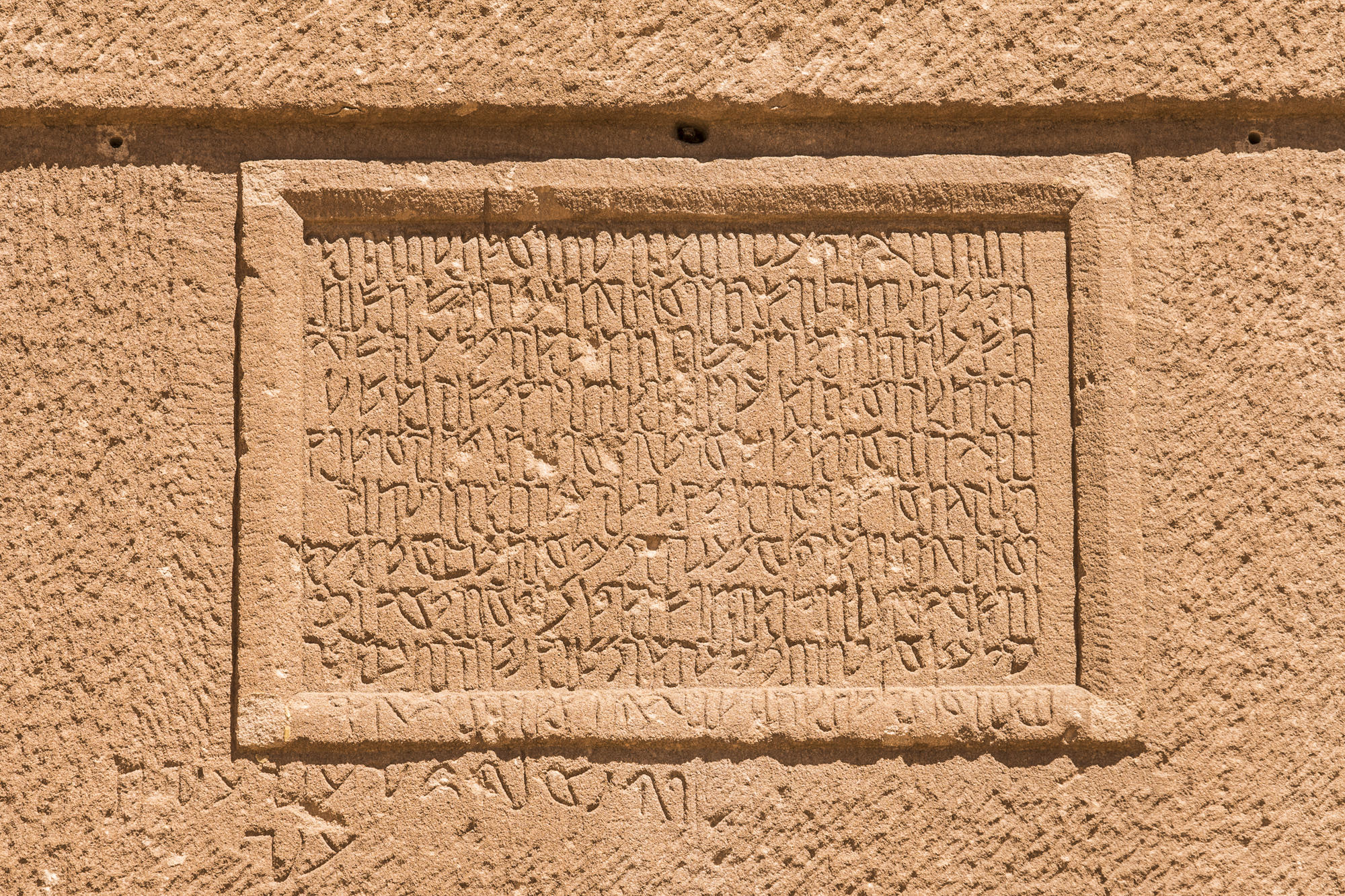

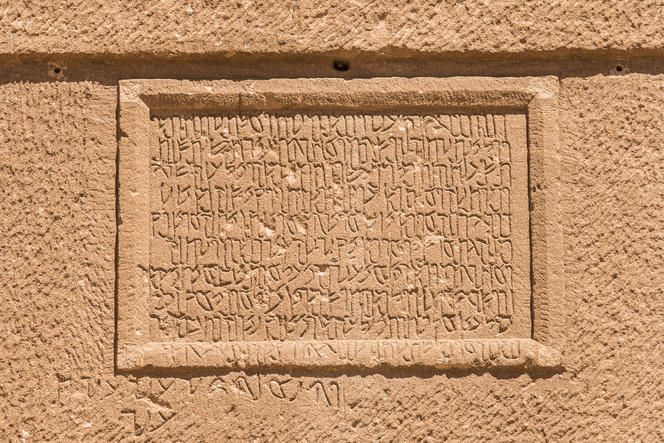

L. N.: At its largest, the Nabataean kingdom, of which Hegra was the southern capital, covered all of southern Syria, Jordan, the northern Arabian peninsula, part of the Negev and possibly the Sinai deserts. After it was annexed by the Romans in 106 AD, this pre-Islamic society disappeared as an autonomous political entity. However, it left a rather remarkable legacy since its script, which is mainly known from the thousands of graffiti engraved into the rocks of Hegra and Petra, gave rise to the Arabic alphabet in use today.

The hundred or so monumental tombs carved into the sandstone cliffs are one of the most spectacular features left by the Nabataean civilization in Hegra. How did the workers manage to cut into a rock face that was sometimes sheer?

L. N.: We showed that these rock tombs, whose cut area varies from 1 to 60, were systematically constructed from the top downwards, and without scaffolding due to the shortage of wood. To start construction, the stonemasons first had to find an access and shape a flat surface in the rock. They would then gradually descend the rock face, carving out the burial chambers. In addition, many of these tombs, unlike those in Petra, the Nabataean capital, bear dated inscriptions that provide valuable information about the deceased, their social status, their families, and so on. One of them, which was found intact, has even enabled us to reconstruct the entire Nabataean funeral ritual. Such practices suggest that the inhabitants of Hegra believed in an afterlife.

Speaking of religion, what gods did the Nabataeans believe in?

L. N.: A male deity, Dushara, took pride of place in their pantheon. However, in Hegra we discovered the remains of a great temple dedicated to a ‘god of Heaven.’ There is no mention of this god anywhere else in the Nabataean realm, so it is highly likely that it was worshipped only in this city. Moreover, to the north-east of the site, we identified an area devoted principally to meetings of religious brotherhoods and accessible only by a narrow corridor approximately fifty metres long (the ‘Jabal Ithlib’). The largest of the rooms carved into the rock (the ‘Dîwân') was a triclinium, i.e. a space with three couches laid out in a U-shape. Members of the brotherhoods used to meet there in groups of twelve, eating in the Roman style (reclining), drinking wine and listening to music. These meals were taken in common to honor the gods, kings, or simply the deceased.

And what did the residential area look like?

L. N.: It spread over an area of 52 hectares in a wide plain located roughly at the centre of the site, and was surrounded by a 3-km mud-brick rampart with several gates, including a monumental door flanked by towers. The city was home to both clusters of dwellings and larger buildings, less densely built up zones and possibly markets, squares and gardens. And it is now certain that the large edifice (at least 85 m × 65 m) adjoining the southern section of the rampart housed the Roman legion that was stationed in Hegra at the beginning of the second century. At that time, the Roman Empire extended much further south than most school textbooks and ancient art museums suggest.

In this arid environment, what was the agricultural practice used to ensure the subsistence of several thousand inhabitants?

L. N.: Hegra was first and foremost an oasis. The aquifer fed 130 wells, which irrigated large areas of crops. We discovered that the local agrosystem was based on the cultivation of date palms as well as cereals (wheat and barley), fruit trees (olives, pomegranates, figs and vines) and legumes (lentils, peas and lucerne). In addition, the presence of fragments of cotton fabric in the tombs, and in particular of cotton seeds in sieved archaeological sediments, strongly suggests that this plant, although water-intensive, was also grown locally. Research over the past fifteen years has also provided a great deal of information about the meat diet of Hegra's inhabitants, while pottery and coins have shed light on trade and the local economy. The data collected in all these areas, and in many others, is being studied by the various specialists taking part in the mission. We will be continuing our research, mainly to find answers to a number of outstanding questions, such as the layout of the Roman camp and of the sanctuary. At the same time, we are going to carry out epigraphic research in Madâ'in Sâlih and its region, in particular to improve our understanding of how Nabataean writing evolved into Arabic script.

- 1. CNRS senior researcher at the Laboratoire Orient et Méditerranée, Textes - Archéologie - Histoire (CNRS/Université Paris-Sorbonne/Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne/EPHE/Collège de France). She co-directs the French-Saudi Archaeological Mission in Madâ'in Sâlih, Saudi Arabia.

Explore more

Author

Philippe Testard-Vaillant is a journalist. He lives and works in south-eastern France. He has also authored and co-authored several books, including Le Guide du Paris savant (Paris: Belin) and Mon corps, la première merveille du monde (Paris: JC Lattès).