You are here

Great Apes, Great Neighbors?

The 80 chimpanzees of Sebitoli, a small island of forest at the north end of Kibale National Park, Uganda, find themselves in a predicament. Isolated from the rest of their kind by an impassable motorway cutting through the park, they’ve seen the tropical forest slowly shrink, under the pressure of economic development. "After intensive logging in the 1970s, which took away half of the wooded area, they are now surrounded by tea plantations and fields of corn and plantains," says Sabrina Krief,1 chimpanzee specialist and scientific co-curator of the exhibition "On the Trail of the Great Apes" now showing at the National Museum of Natural History (MNHN) in Paris. Forced cohabitation creates tensions with local populations: the inhabitants of surrounding villages complain about monkeys stealing from the fields, while 30% of chimpanzees in the area have been wounded by poachers’ traps laid in the forest.

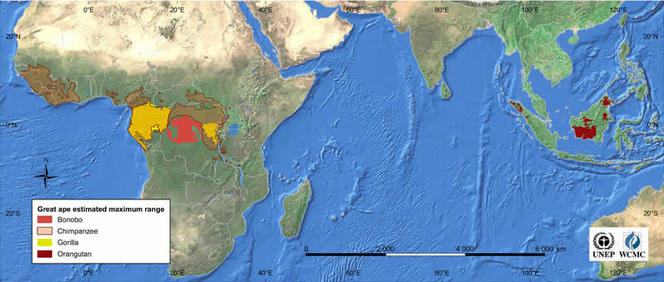

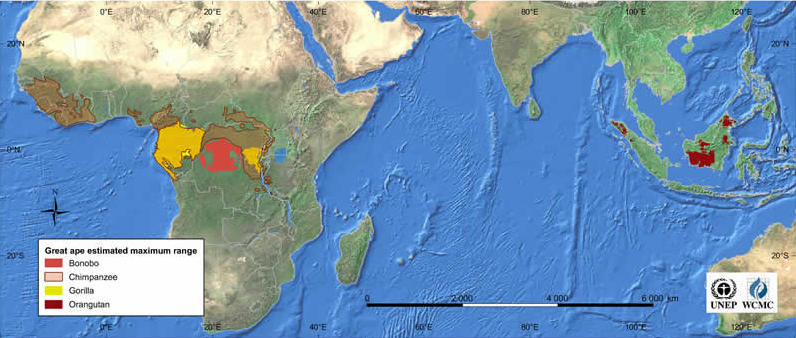

Sebitoli is not an isolated case. Wherever they live, be it Africa (chimpanzees, gorillas and bonobos), or Indonesia and Malaysia (orangutans), great apes suffer from the close proximity of man, which can directly affect their survival. "The situation of the great apes is extremely worrying," says Christophe Boesch, director of the primatology department at the Max Planck Institute. "All, without exception, are on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature's endangered species list and some are in a critical situation." In Sumatra, there are barely 7000 orangutans left of the Pongo abelii species. The Cross River gorillas, an isolated population on the border between Nigeria and Cameroon, number no more than 300; it is almost too late for them. "Like humans, great apes reproduce very slowly, with an average of four young per female in a lifetime. This does not allow rapid population regeneration,” says the primatologist.

Deforestation, poaching and disease

The worst enemy of these primates is deforestation, which destroys their habitat. "Apart from a few chimpanzee communities that can also live in the dry savannah, apes are forest species whose existence depends directly on trees, where they build their nests to sleep at night and feed on the fruit and leaves," explains Boesch. Yet an area of forest 1.5 times the size of Paris is cut down every day. At this rate, only 10% of the great apes’ habitat will be left by 2030. Logging and the rise of intensive slash-and-burn agriculture, aimed at feeding a constantly growing human population, are not the only factors involved.

Mining, both legal and illegal, has a lot to answer for. "The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), is witnessing more and more illegal extraction in the national parks," says Shelly Masi,2 gorilla specialist and lecturer at the MNHN. The main resources targeted are coal, for fuel, but also coltan, a mineral containing tantalum, which is used in electronic devices and has been partly funding the civil war raging in the east of the region. And this is not the only consequence of the ongoing conflict in the eastern DRC: great ape meat poaching by rebels hiding in the forest has also soared.

"Together with deforestation, the other scourge threatening apes is hunting," explains Marc Ancrenaz, director of Hutan, an association for orangutan protection. “In Borneo, an estimated 2000 to 4000 orangutans are killed each year despite the total ban on hunting and trade in great apes adopted by the entire international community." For chimpanzees, among which group cohesion is particularly strong, the damage is tremendous: "For each chimpanzee targeted, about ten individuals are slaughtered trying to defend it," reports Krief. However, attitudes vary from place to place—some human groups refuse to eat great ape meat because they bear too great a resemblance to people. This is the case of the Bateke, an ethnic group in the DRC, with regard to bonobo meat. "According to local beliefs, a man who was deeply in debt was forced to flee into the forest where he turned into a monkey,” says Victor Narat, a bonobo specialist at the MNHN. "Killing a bonobo is therefore equivalent to killing a human being." Prohibiting their consumption as food was not enough to protect bonobos in the area, however. Closeness to the capital, Kinshasa, encouraged intensive farming and an influx of workers less concerned about the fate of these great apes—leading to an increase in poaching in the 1990s.

The last and not the least of the effects of humans and great apes living in close proximity on ever-smaller territories is the transmission of diseases. "Great apes are so similar to us genetically that they are prone to human diseases—the difference is that they are not immunized against them and may die!" says Masi. Gorillas and chimpanzees are particularly susceptible to respiratory conditions transmitted by humans, including tuberculosis, and may even catch the flu. The main vectors are poachers who go deep into the forest, tourists who come to observe the monkeys, and even some scientists if they do not take sufficient precautions, although practices have evolved in recent years: researchers and ecotourists wear masks, human excrement has to be buried, and monkeys must be observed from a distance of at least 10 meters, regardless of the purpose.

Managing the forest

To counter the threats, specialists and conservationists support the establishment of national parks where human activity is strictly prohibited. "This is the best solution to ensure the long term stability of ape populations," insists Boesch. Mountain gorillas in the African Great Lakes (DRC, Rwanda, Uganda) are a good example. Since they have been living in a protected area, these great apes, which received extensive media coverage in the 1980s thanks to Dian Fossey and the film Gorillas in the Mist, have seen their population rise from 500 to 880 individuals. However, although most of the forests in West Africa are still vast and can sustain more of such sites, this is not the case everywhere. In Indonesia and Malaysia, but also in Rwanda, Uganda and Tanzania, population pressure is intense and there is fierce competition for every hectare of land.

"We cannot rely on national parks alone. Today’s reality is that 80% of apes live in unprotected forests,” says Ancrenaz, who proposes to conceive more balanced ways of reconciling the economic interests of the people and the protection of great apes. "Twenty years ago, researchers were convinced that orangutans could only live in the depths of the rainforest. Today, we know they can survive in degraded environments, under certain conditions, which allows us to consider alternative conservation strategies."

One of the most surprising findings in recent decades is that the great apes are much more adaptable than expected and can change their eating habits, notably to adjust to their environment. At Sebitoli, the chimpanzees, animals thought to be exclusively diurnal, have thus started raiding the fields at night to elude the villagers. In Borneo, where forest fruits have become scarce, it is not unusual for orangutans to settle for two or three days in the oil palm crops close to the forest and eat the fruits of this plant, an imported species from Africa.

Forestry management work is nevertheless needed to protect these primates, such as the maintenance of wooded corridors in the areas where the forest is highly fragmented, so that apes can move around between different patches of forest. Another solution implemented by the organization Hutan, in Borneo, is rope bridges enabling orangutans to cross roads safely. On another front, primatologists are trying to persuade industry to change its practices. "We found that sustainable forests facilitate the survival of orangutans," says Ancrenaz, who is also calling on the palm oil industry to leave trees on at least 15% of cleared surfaces, a strategy supported by solid economic arguments as these residual trees limit soil erosion and maintain favorable humidity for palm growth.

Involving local people

"Great ape conservation cannot be achieved without the participation of local populations, and there must be something in it for them," adds Narat. The researcher is closely following the efforts of M’Bou Mon Tour, the only local NGO for the protection of bonobos, located at Bolobo in Bateke territory. "When the association was founded," he explains "its purpose was to help the Bateke defend their environment and living conditions: the forest was running out of game and fish were becoming scarce. From 2001, the locals began to take an interest in bonobos threatened by poaching. They understood that these animals were highly charismatic and could not only generate ecotourism for monkey watching but also attract subsidies from important donors." To balance the exploitation of forest products with the conservation of bonobos, the villagers have created protected areas where only a limited number of human activities are allowed: hunting of any animal is prohibited, as is burning, but fishing is permitted (provided forest wardens are informed) as is the collection of mushrooms and caterpillars. "Today, 60 jobs have been created thanks to the bonobos," the researcher adds.

Other conservation models, used notably in the Central African Republic (CAR), foresee the existence of three distinct areas in the forest: a strictly protected core zone, a buffer zone where activities are supervised, and a reserve dedicated to local people for unrestricted hunting—with the exception, of course, of great apes and other protected species. "There are few food crops in the Central African Republic, as people live almost exclusively on forest products. Denying them access would therefore be unthinkable," says Masi.

Involving local people also helps them see great apes in a different light. In the Dzanga-Sangha reserve, in the south of the country, the researcher and his team work in collaboration with 30 Aka pygmies who are the only people capable of finding evidence of the presence of gorillas in the forest: "They participate with us in the long process of habituation necessary to observe monkeys without making them run away. While they used to think gorillas were aggressive and dangerous, now they are amazed at their resemblance to humans, their intelligence and individual personalities'." What if better knowledge of the great apes was the first step towards a (more) harmonious cohabitation?

To see, to read:

An exhibition entitled Great Apes is on show until March 21, 2016, at the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle in Paris.