You are here

At the Frontier of Materials

Ever wondered why the colored stripes on your toothpaste are perfectly aligned, and do not blend into a flavored foam until you put your toothbrush in your mouth? The answer lies in the work of rheologists like Philippe Coussot. Rheology—etymologically the "science of flow" (from the Greek rheo, meaning “to run or flow”)—is the study of pastes and other materials that can behave either like solids or liquids—or both. It does not take experienced rheologists, such as Coussot and his team at the Laboratoire Navier,1 to use materials that are so many objects of study for these specialists in complexity, at the interface of physics and chemistry. Examples abound: they can be found in cooking, with emulsions like mayonnaise, chocolate mousse, yogurt or even mashed potatoes, and in DIY, with paints, varnishes, mortars, tile adhesives, etc.

Philippe Coussot had a rather dramatic introduction to the fascinating properties of these materials when, as a student at the École Polytechnique in 1988, he served an internship at the national forestry service (ONF) in the French Alps. “My arrival at the ONF in Chambéry happened to coincide with a massive mudslide in the town of Modane, which caused extensive damage,” he recounts. “At the time there were no scientific resources for describing these flows and identifying high-risk zones.” This shortcoming struck him to the point of writing a thesis on the subject. “I tried to classify the various types of materials involved in these slides, and I was able to show that they were threshold fluids—another term for these complex materials—in the majority of cases.”After his thesis, Coussot pursued his study of mudslides along with theoretical work on threshold fluids.

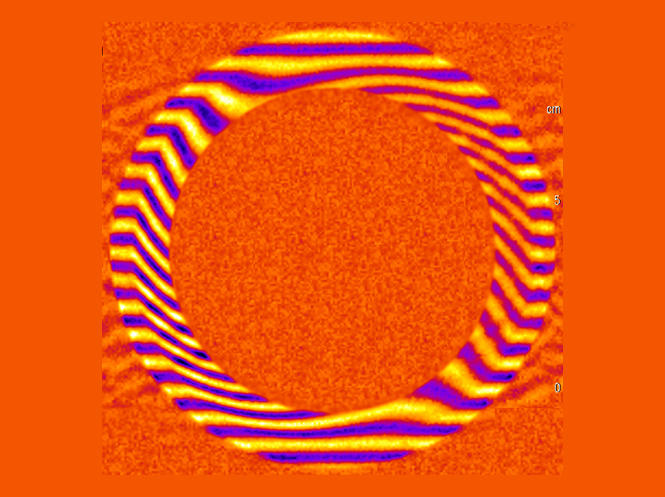

In the late 1990s, with the aim of expanding the scope of his research, he joined the central laboratory of the École des Ponts ParisTech engineering school, to conduct research on a new magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) system specifically developed for the study of civil engineering and environmental materials. “There was tremendous experimental potential,” he says. “At last we would be able to identify a whole range of things in flow materials and porous media.” Acting on a hunch that paid off, Coussot introduced to his discipline a high-resolution rheometer with no real equivalent anywhere in the world. “Combining a rheometer with MRI was well worth a try,” he comments. The rheometer is as essential to the rheologist as the compass to the sailor: it is a key instrument for studying the behavior of complex fluids under the influence of controlled physical stress.

In use since 2002, this unique system enabled Coussot and his team to achieve a worldwide first: characterizing the flow instability, a previously little-understood quality, of thixotropic materials (materials that, beyond a certain level of stress, can suddenly turn from a solid to a liquid). This theoretical advance could lead, for example, to more energy-efficient transport of liquid concrete. “If it’s too thick, it takes huge amounts of energy to pump it through pipes,” the researcher explains. “Therefore, the idea is to keep the material as fluid as possible during the process—but not too fluid, so as to prevent sedimentation.”

Coussot’s work on thixotropic fluids, along with his many other contributions in his chosen field, have earned him international recognition as a direct and respected heir of the US chemist Eugene Cook Bingham, who founded the discipline of rheology in the early 20th century.

- 1. CNRS / École des Ponts ParisTech / IFSTTAR.