You are here

Welcome to Sainte Savine, 130 kilometers South-East of Paris. Here you can find a workshop that works on ancient monuments. Today’s task is to recreate a machine vital to the democracy of Athens.

Today the goal isn’t to restore an ancient monument, but to recreate a machine vital to the democracy of Athens.

Pierre Gaurier

We’ll take a zone and define it as our ‘green zone,’ this is the piece we’ll be workin on..

Then we’ll select the type of process we want…

The tool will come in here and chisel out the material, which allows us to quickly produce something relatively sharp.

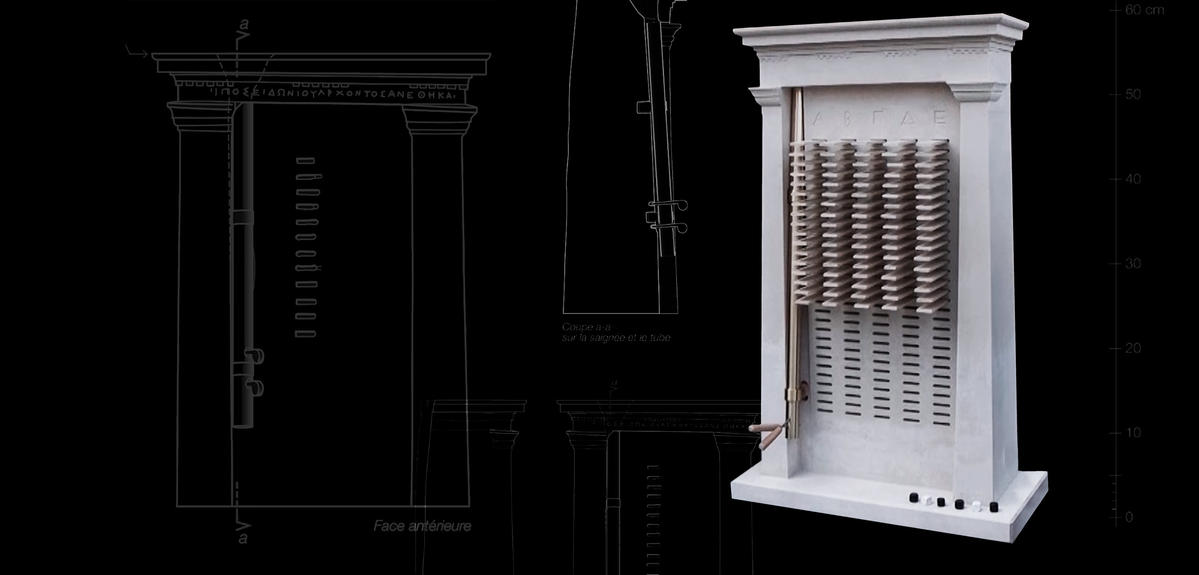

This high-precision robot will ensure the perfect size for our marble block. The goal: to create a Klèrôtèrion. This Ancient Greek device allowed the citizens of Athens to draw lots for the judges of a tribunal or the members of an assembly… those people required to carry out particular public tasks for the city.

An entire Klèrôtèrion has never been discovered intact during excavation… there are only a few physical examples in existence, all incomplete and stored in museums.

The 3D model used today has therefore been extruded from research led by the archaeologists Nicolas Bresch and Lilane Rabatel…

Lilane Rabatel, archaeologist

The design of this machine was based on a text written by Aristotle concerning the constitution of Athens.

This document explained the process of drawing lots, and described the machines that were used. This was matched with our findings as we studied ruins. We feel we can say that we’re on the verge of creating what we might call a prototype of a kleroterion, even though we aren’t sure if they existed exactly like this. With our knowledge of the texts, as well as observations drawn from what relics we can access, this will be effectively the same as a machine drawn straight from the fourth century. The last quarter of the fourth century to be precise.

Nicolas Bresch, archaeologist and architect

The headstone alone is 130kg, and the base is another 20kg. It’s superb! It really is amazing.

Before arriving at this final stone reproduction, Nicolas Bresch had already built numerous iterations in cardboard. In this way they were able to validate a number of hypotheses surrounding the function of this counting machine. But to replicate it in its original form, with the materials of the epoch, allows for a more granular study of the device.

Lilane Rabatel

To us, it seems clear that for our work, to better pursue our research on the operation of this machine, we need to have its components built as closely as possible to the original. In other words, in stone. This enables us to give equal consideration to the constraints imposed by the weight of the objects they would have used, the various accessories, and the problems of fastening it all together which would have been unique to the materials themselves.

The kleroterion, finally built and assembled, can now be tested…

Nicolas Bresch

So the tube goes like this. Now we need to adjust the attachment to the right height, and adjust the angle to align it just right. I have two tools which are inserted here, and which will control the release of the dice.

The people would come with a placard like this, which was called a pinakion.

Liliane Rabatel

Aristotle’s text tells us that the pinakia were made of wood, and more precisely boxwood. Certainly it would have been a very hard wood because they would have wanted to keep the stone from damaging it, so we’re using a relatively dense wood.

All of the citizens who belonged within a certain category would come and place their placard in a box, where they would have been shuffled. Then a selected volunteer would insert the placards within the slots of their marked column. Columns alpha, beta, etc.

This is truly an emblematic tool of democracy.

Yeah, that’s good, huh.

The name of a citizen was inscribed on each of the pinakia. In this example, 85 citizens will participate in the lottery – with 17 rows containing five citizens each.

If one wanted to draw 15 citizens, it would be necessary to select three rows of five people each.

Nicolas Bresch

Thus, we need three white cubes, and how many black?

Lilane Rabatel

14.

Three white cubes to select three rows. 14 black cubes for 14 disqualifications.

Nicolas Bresch

There, we can release the dice at a steady, measured rate. I’ll just withdraw the first insert.

Lilane Rabatel

When we put it back in, between the two inserts, we’re able to alternate between them to isolate a single cube at a time.

As soon as a white cube is released, the five pinakia within that row are used to determine the citizens designated for political roles. Conversely, the citizens of a rung that receives a black cube can leave without being given any work or office.

The selection continues, row after row, until there are 15 citizens out of 85 who have been designated to fill public posts.

Nicolas Bresch

In reality it’s very important that this is done in the open. It was made like this in order to be viewed in open spaces, possibly covered to keep the rain and sun out, and guaranteed that people were truly chosen by chance. That they were honestly shuffled.

Liliane Rabatel

Thus there was also an idea of participation within the operation of the democracy that necessitated each citizen to have an equal chance of taking part in public life.

Thus this Klèrôtèrion gives us a concrete interpretation built solely upon ancient ruins and texts. Destined to be circulated among the public, it will open discussions revolving equally around new and old technology which might bring about innovative methods of organizing public service today.

The Machine that Selected the Citizens of Athens

In the Greek cities of antiquity, a lottery system was devised to select citizens for public duty. For the first time, researchers were able to build a stone replica of a kleroterion, the amazing machine that made this random selection possible.

Nicolas Bresch

Institut de Recherche sur l'Architecture Antique

CNRS / Aix-Marseille Université

Université Lumière Lyon 2 / Université de Pau et des Pays de l'Adour

Pierre Gaurier

Société SNBR