You are here

PHOTO STUDIOS - VANISHING WINDOWS THROUGH TIME

Another History of India - Translated by Jay Swanson

In Southern India, you may come across peculiar fields.

Upon closer inspection, it becomes clear that these are not crops but another type of harvest… on the verge of being blown into oblivion.

These film negatives, slowly eaten away by humidity, are the key components of a desperate attempt at preserving a disappearing heritage. With the arrival of digital photography, film has been rendered obsolete. And photo studios either sell negatives like these to try and salvage the tiny amounts of silver contained in their coating, or they just burn them in order to free some space.

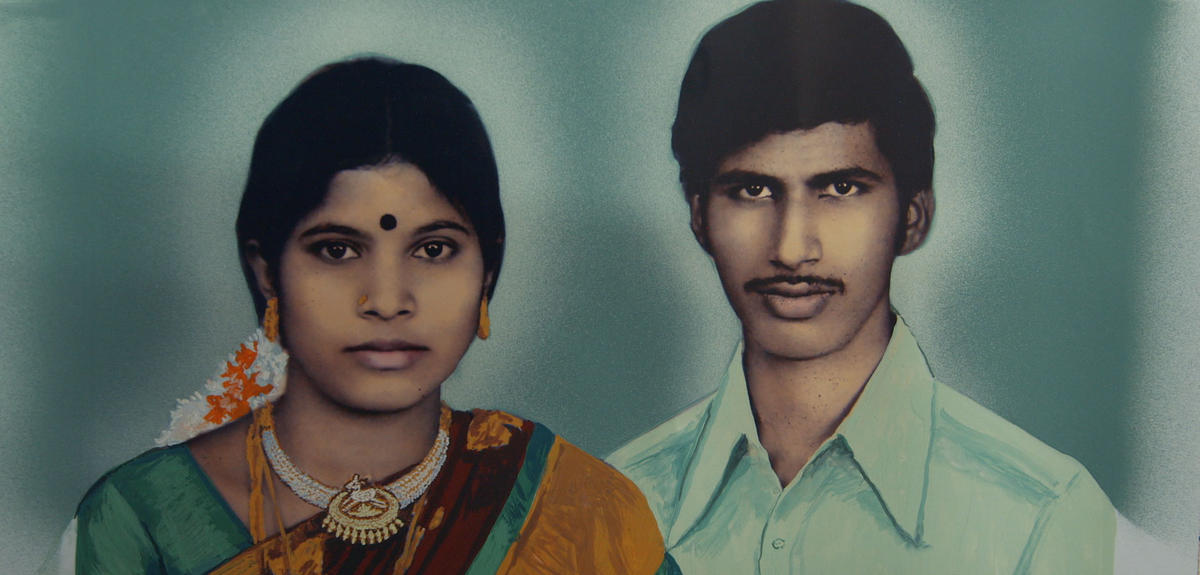

Today, those that have escaped both sales and fires are producing some wonderful surprises. One example: this series of ID photos intended for ration cards in the 70’s.

Traces of pink wash have been discovered on some of the negatives, it’s an old image modification technique which serves as evidence revealing details of the shooting conditions.

Zoe Headley

The pink wash we found on older glass plates was used to sharpen the photo. We usually find it over the face or arms to help lighten the skin. If we find pink wash under the nose or chin, that tells us that the the photo was taken outside before the studio had electricity. It means the scene is being lit by the sun, coming from a high angle and creating a shadow here. So it shows that the photo was probably taken in a daylight studio - a studio where the roof was retracted to use the sun for lighting. Or simply outside.

To save what they can, the research team first isolates moist negatives that could otherwise contaminate the collection, which is then packed in bags. They’ll return in a few months to digitize these photographs and add them to their growing digital library.

Zoe Headley is an anthropologist who has wandered throughout southern India for years, documenting its history through the eyes of these old photo studios.

Few of these locations have survived both time and the steady increase in rent. For over forty years, generations of Indians have come and posed before this painted wall, taking their turn to be immortalized on glass plates and film.

Today, pixels have replaced chemicals and the few clients to come through do so for more utilitarian purposes. It’s in these last remaining studios that Zoe and her team find the necessary scraps to piece together a social and artistic history on the verge of vanishing forever.

Zoe Headley - Anthropologue

One of the things we’re specifically trying to understand is what the social standing was of both the people being photographed, and the photographers themselves. Who were these photographers? Their profession didn’t exist before. Then all of a sudden it appeared within a society built on castes. And castes usually determined professions. So we’re very interested in the social profiles of the photographers, but also of their clients.

For the vast majority of the Indian populus, photo studios were the only place where photography took place until the early 90’s. It’s among the descendents of these local photographers that scientists launched a conservation program to save available negatives. They digitize the negatives on the spot with a mobile setup.

Traditionally, studios guaranteed that prints could be made for their clients for up to 20 years. The film negatives would then be destroyed or sold.

For the owners of these old studios, the arrival of these researchers is an opportunity to bring back long lost memories.

And for the scientists, their search can also lead them to come upon traditions, once thought to have disappeared, but, apparently, still very much alive today.

In the quiet of his workshop, in the district of Madurai, Mohan patiently adds touches of life to these portraits. He’s one of the last remaining masters in a long lineage of photo painters. This tradition persists in India thanks to artisans who, for a long time, occupied a vital role in photo studios. It’s through his art that Mohan has enabled Zoe to unlock certain secrets hidden beneath layers of color in these portraits.

Mohan - Painter

They are from poor family that only have normal photos. They want to see their father or grandfather in a richest way that’s way sometimes they are asking to change a normal sari or a normal costume into a richest one. Sometimes I will decide to make these kind of changes.

If a simple cotton sari in the hands of a painter can be changed into silk, jewels might also be transformed in a way that deceives scientists into believing they are real. By embellishing his models, the painter introduces more uncertainty within India’s social stratification, further complicating anthropologists’ attempts to identify the social standing of those being photographed. It would seem that photo studios, above all, were temples of artifice.

Expensive clothing, jewelry, watches - photographers provided any number of outfits and accessories to dress up clients before taking their photos. These images captured the most important moments families would want to remember forever: births, coming of age rituals, weddings, and sometimes even deaths.

In their Pondichery offices, the teams responsible for this project have assembled a collection of hundreds of photos taken during different periods. Thanks to signatures left at the bottom of the photos by each studio, researchers will be able to find the source and attempt to rediscover these lost studios. For historian Alexandra de Heering, these archives are also a perfect opportunity to question the impact that the access to photography had on Indian society.

Alexandra de Heering - Historian

It’s clear that going to have your portrait taken in a photo studio was an extraordinary event. At the beginning of the last century people only went to see a photographer once or twice in their whole lifetimes. On truly important occasions. These are images that would last and be displayed. Considering how rare they were, it’s likely that many were displayed in people’s homes.

The history of photography has seen nearly 150 different processes put to use, 70 of which were used and adapted within India. Due to constraints imposed by the tropical climate, photographers prefered durable materials like the glass plates used in southern India up to the mid-1960’s.

It’s a fragmented story that requires patient reconstruction, much like a massive jigsaw puzzle, before these photos can be added into a digital library that currently holds over 6,000 images.

This unique archive will be put in the hands of researchers, historians, and artists with the hope of renewing interest in this fragile heritage.

Perhaps tomorrow it will inspire researchers in other regions to collect their own lost memories and help fill more gaps in time.

Jay’s version

PHOTO STUDIOS - VANISHING WINDOWS THROUGH TIME

Another History of India - Translated by Jay Swanson

In Southern India, you can come across peculiar fields.

Upon close inspection, it becomes clear that these are not harvests but another type of culture… on the verge of being blown into oblivion.

These boxes filled with negatives, slowly eaten away by humidity, are the subject of a desperate attempt at preserving a disappearing heritage. With the arrival of digital photography, film has been rendered obsolete, and photo studios either sell negatives like these to try and make their money back, or are likely to burn them just to save space.

Today, those that have escaped both sales and fires are producing some wonderful surprises. One example: this series of ID photos intended for use on rations cards in the 70’s.

Traces of pink wash have been discovered on some of the negatives, evidence of an old retouching technique that reveals details of the shooting conditions.

Zoe Headley

The pink wash we found on older glass plates was also used to sharpen the photo. We usually find it over the face or arms to help lighten the skin. If we find pink wash under the nose or chin, that tells us the the photo was taken outside before the arrival of electricity, because it’s lit by the sun, which comes from a high angle and creates a shadow here. It’s an indication that the photo may have been taken in a daylight studio, a studio whose roof was retracted to use the sun for lighting because there weren’t any electric lights yet.

To save what they can, the research team isolate moist negatives that could otherwise contaminate the archive, which is packed in bags. They’ll return in a few months to digitize these photographs and add them to their growing digital library.

Zoe Headley is an anthropologist who has wandered southern India for years, documenting its history through the eyes of these old photo studios. Few of these locations have survived both time and consistent increases in rent. For over forty years, generations of Indians have come and posed before this painted wall, taking their turn to be immortalized on glass plates and film.

Today, pixels have replaced chemicals and the few clients to come through do so for more utilitarian purposes. It’s in these last remaining studios that Zoe and her team find the necessary scraps to piece together a social and artistic history on the verge of vanishing forever.

Zoe Headley - Anthropologue

One of the things we’re specifically trying to understand is what the social standing was of both the people being photographed, and that of the photographers themselves. Who were these photographers? It’s a profession that didn’t exist before, then appeared within a society built on castes, so where would it have landed? Castes determined professions, so we’re very interested in the social profiles of not only photographers, but the people they photographed.

For the vast majority of the Indian populus, photo studios were the only place that photography was accessible until the early 90’s. It’s among the descendents of these local photographers that scientists have launched a conservation program to save available negatives. They aim to digitize the negatives on the spot with a mobile device.

Traditionally, studios guaranteed that copies could be made for their clients from negatives for up to 20 years. After this point, the negatives would be destroyed or sold. For the owners of these old studios, the arrival of these researchers is an opportunity to awaken lost memories. Among the precious information available to scientists within this troubled trove is the revival of traditions once thought to be lost forever.

In the quiet of his workshop, situated in the district of Madurai, Mohan patiently adds touches of life to these portraits. He’s one of the last remaining masters in a long lineage of photo painters. This tradition persists in India thanks to artisans who, for a long time, have occupied a vital role in photo studios. It’s through his art that Mohan has enabled Zoe to unlock certain secrets hidden beneath layers of color in these portraits.

Mohan - Painter

They are from poor family that only have normal photos. They want to see their father or grandfather in a richest way that’s way sometimes they are asking to change a normal sari or a normal costume into a richest one. Sometimes I will decide to make these kind of changes.

If a simple cotton sari in the hands of a painter is transformed into a silk sari, jewels might also be transformed in a way that deceives scientists into believing they are real. In embellishing his models, the painter introduces more uncertainty within India’s social stratification, further complicating anthropologists’ attempts to identify the social standing of those being photographed. It would seem that photo studios, above all, were temples of artifice.

Expensive clothing, jewelry, watches - photographers provided any number of outfits and accessories to dress up clients before taking their photos. These images also speak to important moments that families would seek to immortalize: births, coming of age rituals posing young girls with their long braids before a mirror, marriages, and sometimes deaths.

In their Pondichery offices, the teams responsible for this project have assembled a collection of hundreds of photos produced during different periods. Thanks to signatures left at the bottom of the photos by each studio, researchers will be able to find the source and attempt to rediscover these lost places. For historian Alexandra de Heering, these archives are also a perfect opportunity to question the impact access to photography had on Indian society.

Alexandra de Heering - Historian

It’s clear that going to have one’s portrait taken in a photo studio was an absolutely extraordinary event. At the beginning of the last century people only went to see a photographer once or twice in their lives, on truly important occasions. These are images that would last and be displayed. Considering how rare they were, it’s likely that many were hung in people’s homes.

The history of photography has seen nearly 150 different processes put to use, 70 of which were used and adapted within India. Due to constraints imposed by the tropical climate, photographers prefered durable materials like the glass plates used in southern India up to the mid-1960’s.

It’s a fragmented story that requires patient reconstruction, much like a massive jigsaw puzzle, before these photos can be added into a digital library that currently holds over 6,000 images.

This unique archive will be put in the hands of researchers, historians, and artists with the hope of renewing interest in this fragile heritage.

Perhaps tomorrow it will inspire researchers in other territories to collect their own lost memories and help fill more gaps in time.

India's Photo Studios: Vanishing Windows Through Time

The advent of digital photography has rendered film obsolete. Photo studios either sell their negatives to salvage the tiny amounts of silver contained in their coating or they just burn them in order to free some space. A team of researchers is trying to collect and save these snapshots of Indian history.

Centre d'Etutdes de l'Inde et de l'Asie du Sud (CEIAS)

CNRS / EHESS

Alexandra de Herring

Cergy Pontoise University

French Institute of Pondicherry (IFP)

Muthusamy Mohan

Painter