You are here

A conference to reverse the biodiversity crisis

Most people today are familiar with the term ‘climate COP’, used to designate the intergovernmental conferences, or Conference of the Parties that address the climate crisis. In fact, they are often referred to simply as ‘COPs’, without specifying the subject. So, what exactly is the COP15, which is being held in Montreal until 19 December?

Philippe Grandcolas: It is an intergovernmental conference that focuses on biodiversity issues. It's held every two years under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), adopted following the Rio Earth Summit in 1992. Nassau Bahamas saw the first biodiversity COP in 1994, while the most recent one, the COP14, took place in Egypt in November 2018. The COP15, under Chinese presidency, was initially supposed to be held in China in 2020. Yet due to the COVID crisis, the event will finally be hosted in Montreal, which is home to the CBD Secretariat.

What's the difference between the biodiversity COP and the Intergovernmental science-policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)?

Ph. G.: The IPBES is to biodiversity what the IPCC is to the climate: an international group of experts responsible for assessing the state of scientific knowledge on the evolution, causes and impacts of biodiversity. Its most recent report,1 published in 2019, is today THE reference document providing evidence of the major biodiversity loss we are facing today.

The notion of ‘climate crisis’ has become widespread. Is there such a thing as a biodiversity crisis?

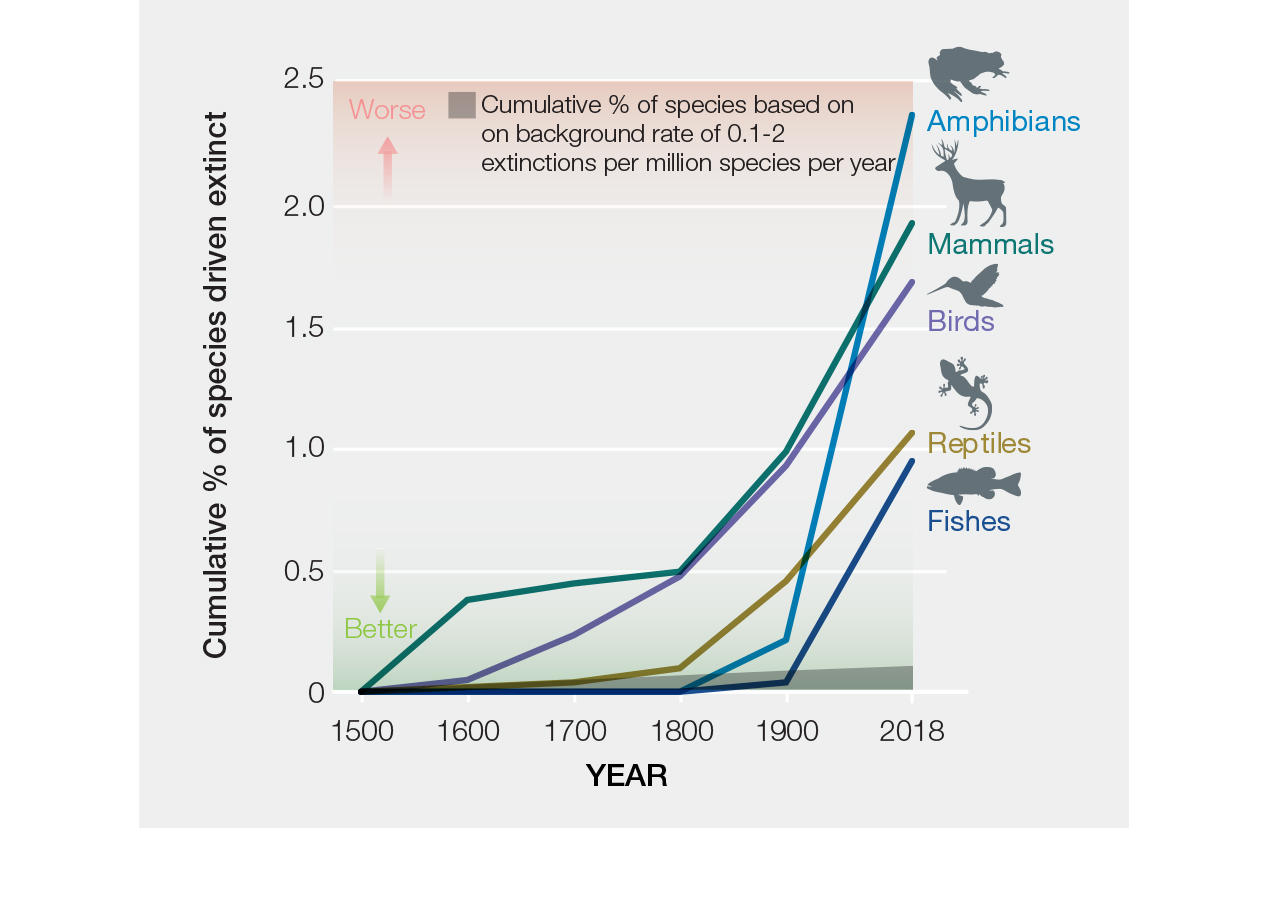

Ph. G.: Yes, we really are facing a crisis of the living world, although it is nothing new. For over fifty years, a host of scientists have been sounding the alarm bell about biodiversity loss. In the 2000s, synthesis of the available data enabled us to grasp the magnitude of the phenomenon, and it was around then that the term ‘sixth extinction’ was coined. However, unlike the five mass extinctions that have marked the history of life on Earth – the most recent of which, at the end of the Cretaceous, saw the decline and disappearance of the dinosaurs – today’s is not due to an event of volcanic or even cosmic origin, such as an asteroid impact. On the contrary, this sixth extinction is caused solely by human activity.

At what rate are species disappearing today?

Ph. G.: According to various estimates, between 2 and 20% of species have become extinct since the Industrial Revolution. Of the 2.3 million currently identified, and the 8 to 10 million believed to exist (excluding viruses, bacteria and archaea), one million are in a critical state and threatened with extinction by the end of the century, including a third of existing fish, a third of reef-building corals, 40% of amphibians, 25% of mammals, 35% of conifers, to name but a few. This is 1000 times greater than the normal rate at which species disappear outside of periods of mass extinction, and is also much faster than in earlier crises. And we humans are directly concerned: at the time of the last mass extinction, 65 million years ago, our species hadn't yet come into existence.

What are the main causes of biodiversity loss?

Ph. G.: They number five. The first one is the loss of natural habitats, especially due to deforestation and the elimination of wetlands, in order to make way for agriculture and other human activities. Then there is overexploitation of resources, including overfishing. Another major factor is pollution caused by pesticides used in intensive agriculture, nitrogen fertilisers, and plastics, not to mention the thousands of synthetic chemical compounds released into the environment. Climate change is also a direct threat to biodiversity – think of rising ocean temperatures and the danger this poses to coral ecosystems, for instance. The connection between climate and biodiversity is crucial, since loss of the latter in turn directly impacts global warming: when the ocean's biological carbon pump is damaged, it loses its ability to sequester atmospheric CO2.

What is the fifth reason for the biodiversity crisis?

Ph. G.: Invasive alien species, in other words, all the animals and plants that are accidentally or deliberately introduced by humans into environments other than the one in which they originated, and that subsequently enter into direct competition with local species, or even end up replacing them. This phenomenon has dramatically accelerated with the boom in air and maritime transport in recent decades, the cost of which has been calculated by scientists: between 1970 and 2017, biological invasions cost our societies $1,288 billion. For example, the Asian tiger mosquito now spreading through France is potentially a vector of diseases such as dengue, Zika fever and chikungunya, while the Asian hornet that arrived in Europe a few years ago is a real threat, especially to honeybees.

Cynics might reply that we can perfectly well live with fewer species on Earth, and that the disappearance of the odd peat bog or amphibian won't fundamentally change the world.

Ph. G.: They would be wrong. At the rate at which species are disappearing, we will end up with extremely impoverished or destabilised ecosystems that are no longer able to provide the services we take for granted today, such as capturing atmospheric CO2 or pollinating crops. Habitat loss and ecosystem fragmentation pose another very real risk for us humans, namely the appearance of new illnesses. In the last 50 years, there have been a record 300 peaks in the emergence of infectious diseases. The greater the interface between reservoir animals and humans, the more contacts there are between them, the more likely that a pathogen is transferred from animal to human. In 2022, for example, a new tick-borne bacterial disease, Sparouine anaplasmosis, was detected in a gold miner in French Guiana.

What will be the main topics discussed at the COP15?

Ph. G.: The focus will be on very general questions such as combatting deforestation, reducing pollution, and restoring damaged ecosystems. Recommendations by previous COPs in this regard have not been implemented, indeed far from it. In 2010, twenty targets were set at the COP in Aichi (Japan) for the period 2011-2020, of which barely six have been achieved.

In my view, one of the most eagerly-awaited topics of this COP15 is the need to increase the number and size of protected regions worldwide. The declared intention is to preserve 30% of marine and terrestrial expanses, whereas today only 10% of the land and 5% of the oceans enjoy this kind of status. A number of pitfalls remain in setting up such areas. The level of protection varies from one zone to another, but it's still better to have 30% that are poorly protected than a mere 10%. Another fundamental challenge is to involve indigenous peoples rather than excluding them, as is shamefully still too often the case.

Another crucial idea to be discussed is the creation of a global financing fund, to which all countries would contribute on the basis of their national incomes. When it comes to preserving biodiversity, money is often a limiting or constraining factor: for many countries, protecting, restoring, and phasing out the industrial agriculture model is extremely expensive.

What are the possible sticking points at the COP15?

Ph. G.: Many members seem to agree on the main principles, but it's when it comes to implementing them that disagreements arise. Although the countries of the global South have the richest and most threatened biodiversity – the majority of the planet's hotspots are found in tropical regions –, it is those of the global North that have the necessary financial resources. However, in a globalised world, things aren't always straightforward: many countries are involved in biodiversity loss at a distance, for example through imported deforestation – part of the soybeans fed to livestock in the North comes from Amazonia – or through the sale in the South of pesticides banned at home because they are considered too environmentally harmful.

Unlike the climate crisis, which seems to be a given today, it seems that neither the general public nor political and economic leaders are aware of just how serious this biodiversity crisis is.

Ph. G.: In my opinion, the real difference between the climate and the biodiversity crisis lies in the way risks are perceived. The growing number of hazards connected to climate change, such as droughts, heat waves and megafires, is clearly visible, which inspires fear. At the same time nobody seems to be conscious of the dangers directly attributable to biodiversity loss, such as new epidemics caused by ecosystem fragmentation, or the scale of certain floods resulting from the destruction of plant cover. We need to considerably raise public awareness of this question. That's another thing that makes this COP15 so important: it's an opportunity to inform people about biodiversity-related issues, and explain them clearly.