You are here

European Research in Focus

With a hefty 79 billion euros, the European Union hasn't forgotten science. Its ambitious H2020 framework program has been supporting research and transnational initiatives since 2013, the same year that the French Ministry of Higher Education and Research, then headed by Geniève Fioraso, launched the Stars of Europe national competition to encourage French laboratories to take full advantage of this fund.

Each year, a scientific jury under the supervision of UMPC1 president Jean Chambaz, rewards 12 projects (for the European flag's 12 stars) coordinated by French teams. The 2017 ceremony was held on December 4th at the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris, during the 4th Horizon 2020 Forum. Of the many laureates whose work reflects the will to develop initiatives across Europe, three are led by CNRS researchers.

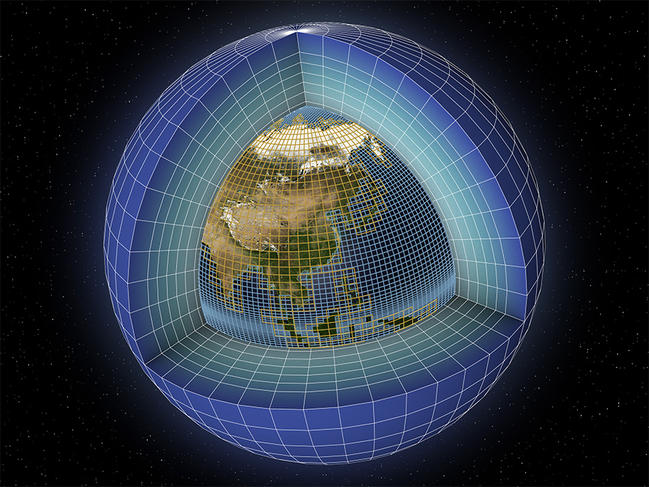

Better climate models

As far as international cooperation goes, few topics require the involvement of such a large research community as climate change. Between the complex reports of the IPCC2 and the many international and interdisciplinary programs, this area of study needs solid international frameworks. IS-ENES23 is one such infrastructure that helps coordinate the work of the European research community specialized in climate modeling, which earned it a 2017 Stars of Europe award.

Sylvie Joussaume, senior researcher at the LSCE4 and former director of the CNRS's INSU,5 coordinates the project via the Pierre Simon Laplace Institute. A specialist in climate modeling, with a focus on ancient climates, she is perfectly aware of the field's many constraints.

"The three main aspects of climate modeling all require solid infrastructures. The models themselves are made up of numerical codes that are often very complex. Powerful computing resources are essential for creating the models, and managing the massive amount of data collected is key for sharing it with the world," explains Joussaume.

This is why the IS-ENES26 shares codes and tools capable of creating these massive climate simulations, "for example to couple the interactions between the atmosphere and the ocean," adds the scientist. This reinforces the efficiency of European teams. The project also helps maintain, standardize and build up the ESGF's7 two million gigabyte database.

"I hope that Europe will continue to help and strengthen the climate science community. For example, at first the ESGF database was mostly developed by the US. But the IS-ENES has become the European partner capable of interacting with the american agencies. This would not be possible without this project, and without the expertise of these European teams," enthuses the researcher.

Atomic resolution

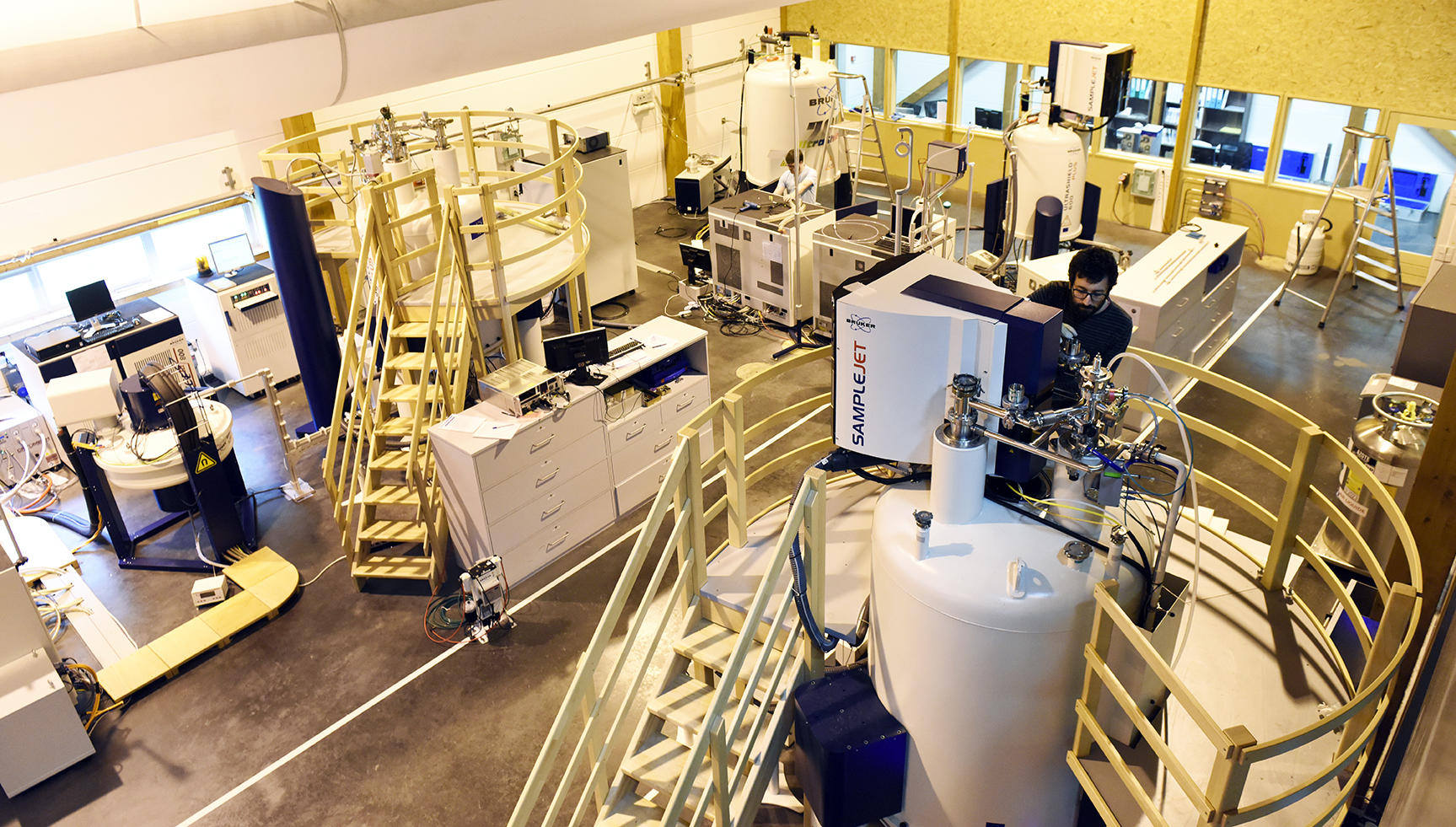

If climate change affects the world at large, the 2017 Stars of Europe are also shining on the infinitely small. Able to analyze matter on the atomic scale, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy has become essential to the scientific community as well as industry.

To increase both resolution and sensitivity of this cutting-edge technology, nine research teams and four companies have joined forces in the award-winning pNMR8 consortium. Guido Pintacuda, senior director at ISA,9 coordinates this now internationally-renowned platform.

"Before this project, NMR didn't work very well on paramagnetic ions," says Guido Pintacuda. "But our network has shown not only that they can be studied using this technology, by that their presence can also improve NMR."

Many transition metals like iron, cobalt, copper, or lanthanides have lone pair electrons that made their study by NMR difficult. But not anymore, thanks to the work carried out by researchers at the pRMN. These advances are of significant interest to the fields of chemistry, biology, medicine, materials science, etc.

From France to Finland via Slovakia, the pRMN has established strong links across Europe. The network has boosted experience and training opportunities for a generation of young researchers, as well as attracted new funding, and helped make NMR more accessible beyond basic research.

"The team is very honored to receive this award," says Guido Pintacuda. "While some question Europe's research performance, our project shows how effective it is in funding international teams. Our network has helped bring together expertise that could not be found in a single country. I am also delighted because three young researchers who trained at laboratories associated to this project have since obtained prestigious teaching positions in Stockholm, the Max Planck Institute and Santa Barbara."

Nanotech goes green

Still in the field of big science—although at small scale—the work of GreeNanoFilms also earned its 2017 Star of Europe. This European project, launched in 2014 around the Cermav10 and involving ten European academic and industrial partners, focuses on environmentally-friendly nanotechnologies. "What we do at GreeNanoFilms is make thin films by self-assembling biosourced copolymers or glycopolymers," explains Redouane Borsali, senior researcher at the CNRS and coordinator of the project. "These materials have a better performance than those made from petroleum derivatives." Glycopolymers are polymers made from sugars—of which the best known natural examples are cellulose and starch. Created with biomass, they are shaped with abundant and renewable resources.

The GreeNanoFilms researchers have become experts at manipulating these elementary bricks, and are now capable of making them self-assemble to form nanostructured films with a resolution of 5 nanometers. The many applications range from high-efficiency photovoltaic films to nanolithography, as well as a variety of flexible biosensors.

"We were extremely happy to receive the prize, and we have the feeling of having accomplished something important as a team," concludes Redouane Borsali. "Thanks to the CNRS, we were able to put together the latest equipment and the skills needed for this project. "

- 1. Université Pierre et Marie Curie.

- 2. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- 3. Infrastructure for the European Network for Earth System modeling— Phase 2.

- 4. Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement (CNRS/Université Saint-Quentin/CEA).

- 5. Institut National des Sciences de l’Univers (CNRS).

- 6. CNRS/Université Versailles Saint-Quentin/CEA/ENS Paris/École Polytechnique/IRD/Université Paris Diderot/Université Paris-Est Créteil Val-de-Marne/UPMC.

- 7. Earth System Grid Federation.

- 8. Paramagnetic nuclear magnetic resonance.

- 9. Institut des sciences analytiques (CNRS/ENS Lyon/Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1).

- 10. Centre de recherches sur les macromolécules végétales (CNRS).

Explore more

Author

A graduate from the School of Journalism in Lille, Martin Koppe has worked for a number of publications including Dossiers d’archéologie, Science et Vie Junior and La Recherche, as well the website Maxisciences.com. He also holds degrees in art history, archaeometry, and epistemology.