You are here

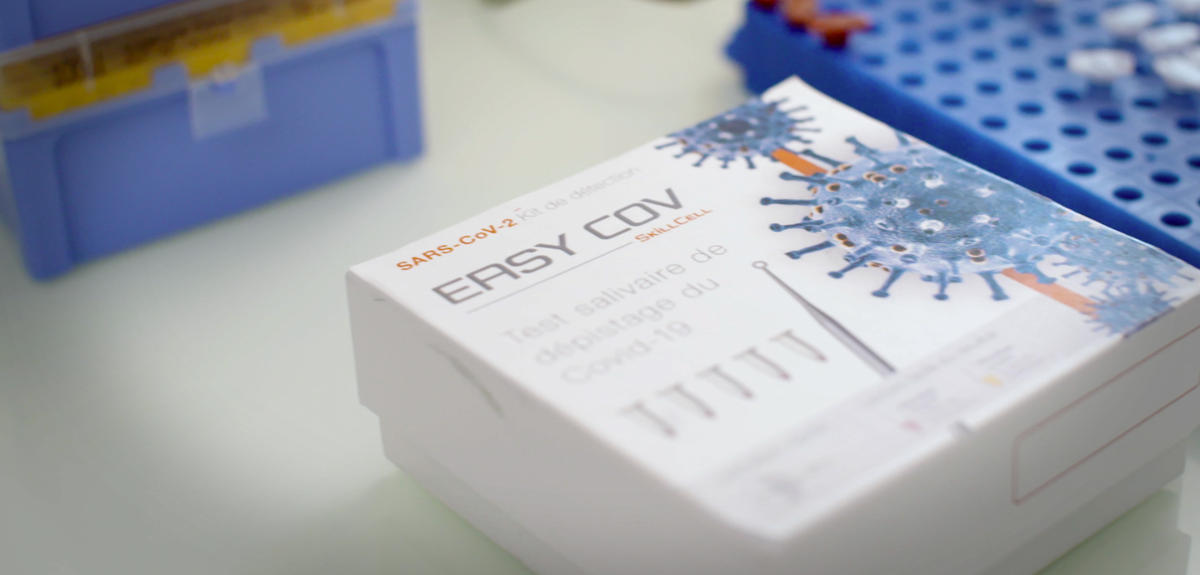

What if COVID-19 tests were as easy as taking a saliva sample?

Pierre CHAMPIGNEUX – Bioengineer

We put 200 microliters of saliva in this first tube, a pre-treatment tube, and we’ll heat it to 65 degrees Celsius for 30 minutes. This way we have a usable sample that can be handled and, above all, it free up the genetic material of the virus that we’ll then detect in a second tube.

In order to find the virus, it’s necessary to extract its “ID card,” its RNA. RNA is transcribed into DNA which can be “amplified,” multiplied numerous times in order to obtain detectable quantities. All of this is made possible with a technique called RT-LAMP, which has the advantage of being simple, quick, and inexpensive.

After an hour in the heat, a colorimetric indicator reveals the EasyCov test result: Orange, you’re negative. Yellow, you’re positive.

Franck MOLINA – Biologist

This test isn’t made to replace existing lab tests, it’s made to put tests where there aren’t labs. For example we could put them at the entrance to nursing homes, confined spaces like prisons, or maybe check the saliva of patients entering the dentist office. All of this could act as a filter to prevent COVID-positive patients from getting through to the other side.

The team has also made EasyCov Reader, a mobile app that enables results to be verified by a trained physician and then transmitted to health authorities, who track the evolution of the pandemic.

First marketed to laboratories, this test could soon be available in doctors’ offices in cities across France. They’re also looking to work with countries in Asia and South America.

Today we already have the capacity to make tens of thousands of tests per day, with room to push that even higher. So it’s not a limitation of scaling production, but how to put them into action in the field as everything is so new.

It was here, at a CNRS research lab in Montpellier, that this new system was developed. And under extraordinary conditions. The day before lockdown, to ensure his team could keep up with their work remotely, Franck Molina took a risky bet.

COVID hit quickly, and wasn’t our specialty, but as we were watching things unfold we thought, ‘We’re a diagnostic medical lab, isn’t there something we could do?’ In the end we decided to take a gamble and look at saliva, because everyone knew the virus was infecting people by aerosol. And while it was a logical place to look, we didn’t know what the viral load was back in March.

But while taking saliva samples may be simpler than taking nasal samples, detecting the virus in saliva is trickier.

In saliva, we find a lot of different chemicals, along with salts, there’s bacteria, followed by our own cells and eventually the virus. The problem with all of this is that if we put it in a tube, it will inhibit the RT-PCR. The game is to prevent the complexity of the sample from hampering detection.

To advance more quickly, the team relied on well established technologies used in their day to day research. But in order to put together a new test in record time, every team member had to up their game.

To invent a diagnostic test, it usually takes six to seven years when all is said and done. So when the COVID crisis arose, even while the test was in the process of being invented, we worked quickly on industrializing it, to secure the reagents which were in high demand, and simultaneously clinically validate it. That’s what enabled us to get it out to production in a total of three months with clinical verification and everything. The only way to get there was if everyone, the clinics, the research teams, and industrial facilities, everyone came together on the same project.

Based on the first clinical studies, the EasyCov test is 87% reliable, equivalent, or even better than nasal tests. The goal for the coming months: reduce the time it takes to get a result as well as improve its sensitivity. And then perhaps to put a dent in the biggest global pandemic in a century.

A promising salivary test

Scientists have developed an easy and cheap solution to Covid-19 testing. The saliva-based test EasyCov can be done anywhere, and provides accurate results in under an hour.

Pierre Champigneux

Modélisation et ingénierie des systèmes complexes

biologiques pour le diagnostic (Sys2Diag)

CNRS / ALCEN-PMB