You are here

When the Lab Enters the Museum

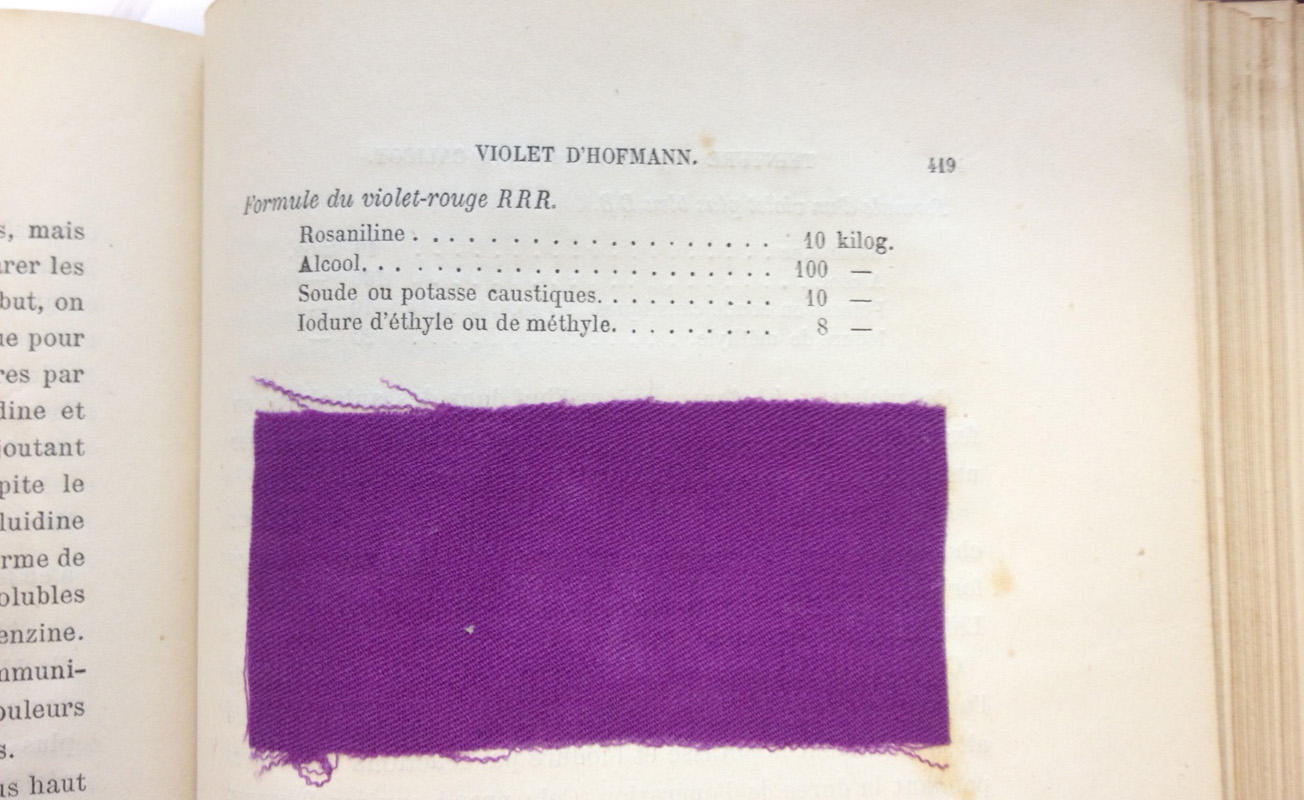

Many analyses require taking samples, but what if the object of study is an invaluable painting by a master? Science offers different options for conducting research on works that must be moved as little as possible—and not be damaged. Over the last three years, the Lams1 in Paris has therefore set up a mobile laboratory capable of revealing the secrets of paintings within the museums themselves, and without having to take samples.

A mobile analysis device

Some of the laboratory's instruments were designed to weigh no more than a few kilos and fit inside a suitcase. All of them are so flexible that it is possible to analyze a painting without having to take it down. As a general rule, it is the Lams that seeks out museums based on their collections. Researchers can thus study the history of color techniques—not just in art, but also in the fields of cosmetics and pharmaceuticals. They also seek to establish dating, and look into the processes of ageing and alteration of materials, especially those of biological origin.

Other machines are designed on site, in order to be perfectly adapted to the analysis of paintings. This ensures that no damage is caused, and makes it possible to focus on artwork of large dimensions. The specificities of the many devices can be combined to suit the research areas of the Lams.

The influence of science on the paintings of Nicolas Poussin

"Our X-ray diffraction instrument, combined with X-ray fluorescence, enables us to perform crystallographic analysis directly on a painting," enthuses Philippe Walter, senior researcher at the Lams, and visiting professor at the Collège de France in 2014. "This helps identify pigments that are otherwise difficult to detect, such as lapis lazuli, used for its blue color. We are also working on white lead, a lead carbonate also known as cerussite. Its fascinating complexity, along with the study of textual sources, sheds light on the quality of the various formulas used since antiquity."

"The painter has something in mind, but is limited by the tools and materials available" the researcher continues. "We are seeking to elucidate this relation. For instance, we are currently working on Nicolas Poussin to measure the influence of the new scientific theories of the seventeenth century on a famous artist of that time. Poussin was actually a member of intellectual circles in Rome that were influenced by the discoveries of Galileo. This is reflected in his representation of a stormy atmosphere, using a superposition of materials and undercoats, or different yellow pigments to depict the light or shadowed parts of a yellow coat."

This research on Nicolas Poussin led researchers to both the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge (UK) and the musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen (northwestern France), and will soon take them to the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff (UK). The Lams mobile laboratory team is especially interested in polychromy within the framework of an interdisciplinary program coordinated by Walter and Charlotte Ribeyrol, an academic at the Université Paris-Sorbonne. The Lams focuses on three periods in particular: prehistory, Greek antiquity and nineteenth-century England. Chemistry and art history are supported by literature and historical sources.

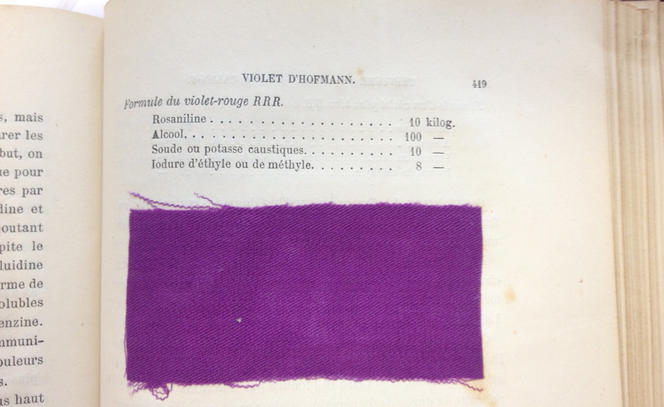

The birth of mauve

"The issue is one of understanding the evolution of taste and culture as they were constrained by the materials available to artists and craftsmen," explains Walter. "The nineteenth century thus saw the invention of mauveine by William Perkin. It was the first synthetic dye in history. Until then, mauve simply did not exist. It became very popular in painting, textiles, and even poetry. This trend reached its climax when Queen Victoria began wearing mauve, just as the Empress Eugénie did later."

The emergence of synthetic pigments and paint in tubes in the nineteenth century radically changed the relation between painters and materials. Today, artists enjoy a plethora of binders and pigments compared with the limited number of pigments that Leonardo da Vinci prepared himself in his time.

The mobile laboratory's next destination will be the Bardo National Museum in Tunis. Walter and his colleague, Laurence de Viguerie, will be accompanied by François Baratte, an academic at Paris-Sorbonne and a number of colleagues from the Orient et Méditerranée2 unit, in order to analyze remains of polychromy on Roman marbles. The use of color on these statues is less known than that of their Greek cousins, and thus requires further study. Yet it is unthinkable to move the more than 3000 marble objects in the Bardo collections. Hence the researchers have no other option but to cross the Mediterranean. In such conditions, the value of a mobile laboratory is quite obvious.

Explore more

Author

A graduate from the School of Journalism in Lille, Martin Koppe has worked for a number of publications including Dossiers d’archéologie, Science et Vie Junior and La Recherche, as well the website Maxisciences.com. He also holds degrees in art history, archaeometry, and epistemology.

To read / To see

Philippe Walter, Sur la palette de l’artiste. La physico-chimie dans la création artistique,

(Paris: Collège de France/Fayard, coll. « Leçons inaugurales du Collège de France »,

2014).