What Makes our Continents Dance?

You are here

Lire en français [2]

Lire en français [2]What Makes our Continents Dance?

The surface of the Earth—the lithosphere—is divided like a giant puzzle into rocky plates that move in relation to one another. This phenomenon, which is referred to as plate tectonics and is unique in our Solar System, ceaselessly changes the face of our planet: it is behind continental drift, the formation of mountain chains, volcanic activity, and earthquakes.

An enigma stretching back half a century

An important question remained unanswered since the late 1960s and the emergence of the theory of plate tectonics: what forces are responsible for the movement of these famous plates? Two different points of view have emerged in the scientific community in an attempt to solve this mystery. For some, the geological dance of plate tectonics is driven by SubductionFermerphenomenon in which an oceanic plate moves beneath another tectonic plate of lower density. zones, in which oceanic plates slip beneath nearby plates and sink into the underlying mantle. During this process, the weight of one falling plate would be enough to pull the rest of the plate, thereby setting it in motion.

Others believe it is caused by the movement of material in the lower mantle known as convection: the heat released by the depths of the Earth lifts the deepest rocks toward the surface, which cool and settle back down. This moving matter "rubs" against the lithospheric plates, thereby dragging them.

A supercomputer to better see the Earth's past

For the first time in 50 years, a team of researchers from two CNRS laboratories, the Laboratoire de géologie de l’École normale supérieure1 (LG-ENS) and the Institut des sciences de la Terre2 (Isterre), along with the University of Rome, have finally settled the debate. Using a 3D simulation created after nine months of calculations on a supercomputer,3 the geophysicists have shown that the movement of tectonic plates is actually the result of both of these phenomena at once, and that their relative contribution has evolved during the Earth's geological history.

Until present, the only solution available to scientists to better understand plate movement was to analyse the data collected from the Earth (satellite data, studies of rocks, seismic data). The only problem is that this data does not stretch sufficiently far into our planet's past, because tectonic plates are constantly recycling. Oceanic plates are created near oceanic ridges, where material from the mantle solidifies before sinking into the mantle in subduction zones. As a result, very little of the oceanic lithosphere dates back more than 180 million years, whereas the Earth is 4.5 billion years old!

1.5 billion years simulated

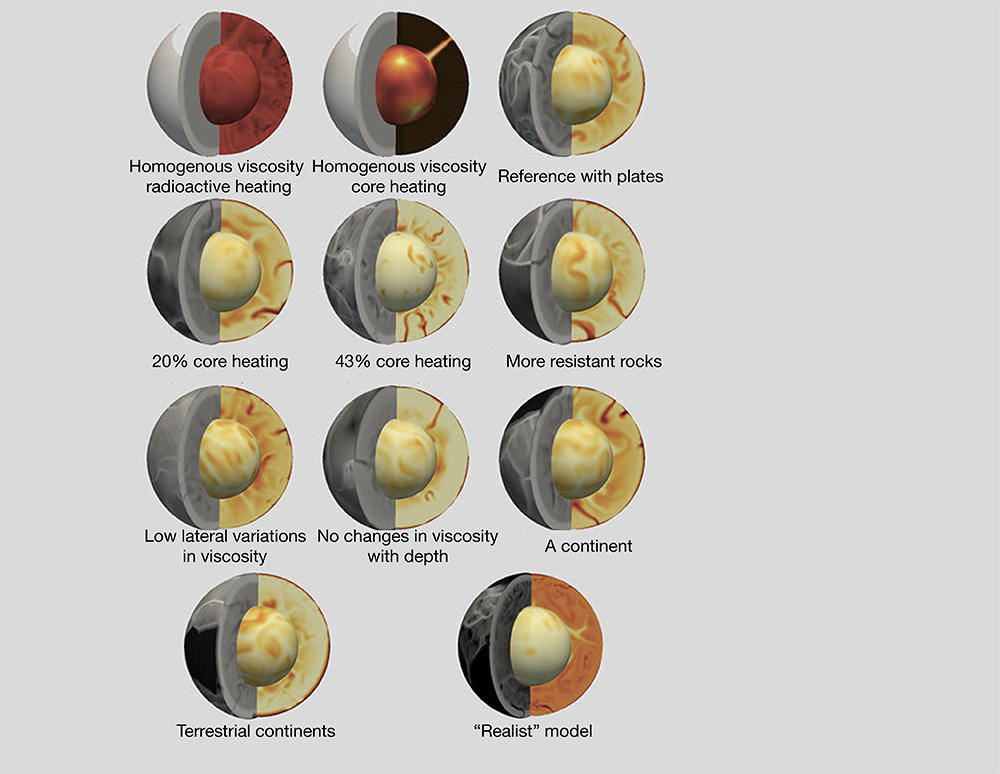

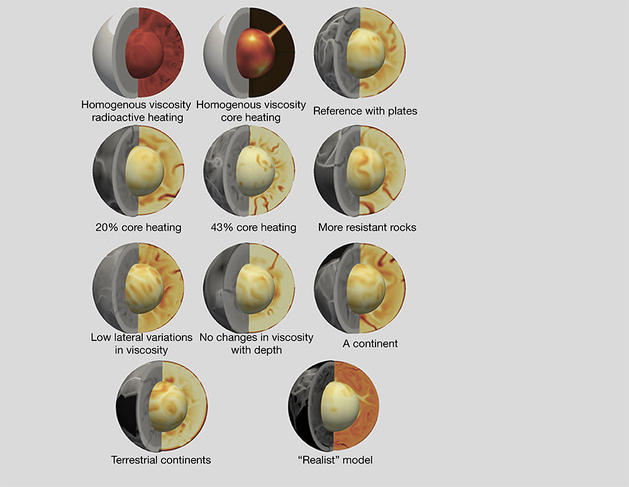

Nicolas Coltice from LG-ENS, Laurent Husson from Isterre, and their colleagues therefore chose a different strategy enabling them to virtually study plate movements over a much longer period of time. To do so the researchers created a 3D digital model of a fictitious planet with properties similar to those of the Earth. The simulation, which was conducted using a supercomputer, traced the evolution of this virtual planet's surface over 1.5 billion years, a time interval that is long enough to identify the causes of plate movement.

This is not the first time that geophysicists have used virtual planets to better understand the dynamics of our Earth, although this simulation is the most fully developed to date, for a number of reasons. The first is in terms of resolution. Like in a weather model, researchers divided their digital planet into no less than 50 million cells—cubes measuring 25 kilometres (km) on each side—across the entire volume of the lithosphere and mantle (up to an approximate depth of 3,000 km). This extremely fine division is, incidentally, why the simulation required nine months of calculations, which involved the identification of a series of parameters for each cell at each stage in time—every 5,000 years—during the entire 1.5 billion years simulated.

A reduced and realistic model of the Earth

The second is in terms of its realism. "We very faithfully modelled the mechanical behaviour of rocks from the lithosphere and mantle, which is to say how they are deformed when they are subject to stress. This simulation is the culmination of five years of work," explains Coltice.

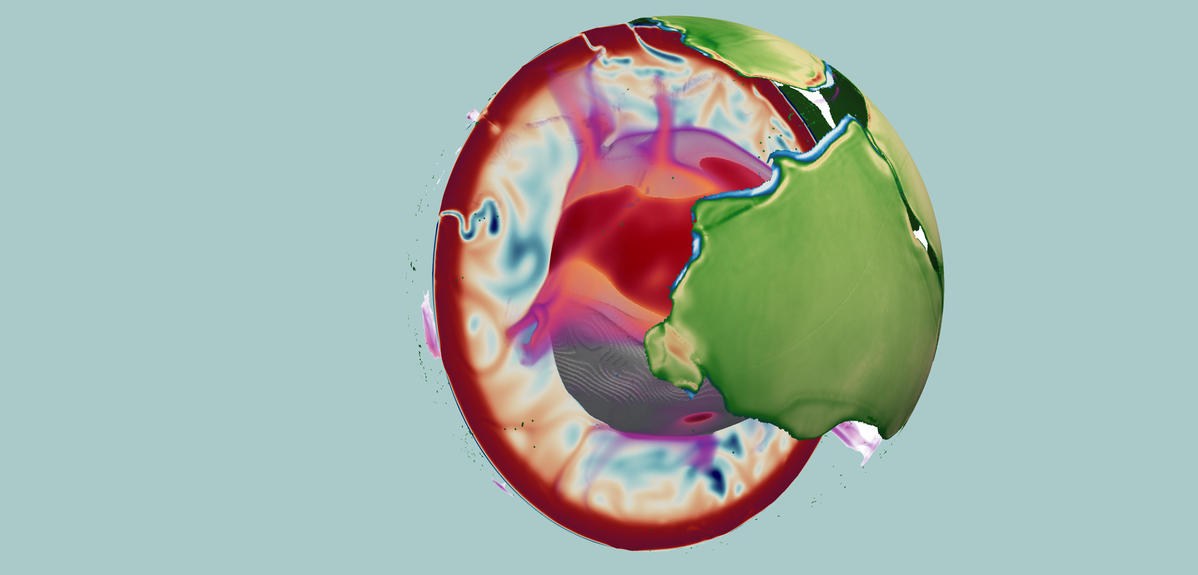

The geologists now had to determine the initial temperature for each cell in this virtual globe, in such a way as to initiate the convection movements of material inside the mantle, as described by the laws of fluid mechanics. The simulation then followed the evolution of these convective movements, as well as their effects on the deformation of the surface. The researchers watched as structures with characteristics comparable to those on Earth emerged before their eyes, including mountainous areas measuring 10 km in height, underwater trenches 15 km in depth, the presence of subduction zones and ridge zones, as well as the appearance and disappearance of supercontinents. Even the average speed of displacement for the virtual plates (a few centimetres per year), and the simulated surface heat flow, were similar to values observed for our planet. In short, the scientists had created a digital twin for our Earth.

For the researchers, the key to this success was to consider tectonic plates and the mantle as one and the same system. "Previously we had a tendency to describe the movement of plates independently of mantle convection, and vice versa. Here we simulated both simultaneously, for plate tectonics is no more than the surface manifestation of convection, with subduction zones corresponding to large cold flows moving downward, in opposition to large hot flows moving upward. Surface plates began to move naturally, without our imposing any kind of velocity on them," Husson points out.

Plates that drive, but not always

The simulation allowed the team to show that for the last 500 million years at least, two thirds of the Earth's surface has been moving faster than the underlying mantle, with these roles being inversed in the remaining third. Put another way, "in the majority of cases the mantle resists plate movement, with the cause for this movement subsequently being located on the surface in the subduction zones that pull the entire plate. However in one third of cases, the mantle pushes the surface with it, and so deep flows are what cause this movement," Coltice adds. A possible explanation for this assessment is that within subduction zones, the forces that pull the surface are more localized and therefore more intense, while the forces exerted by the hot upwellings are more spread out and therefore more diffuse.

Another important observation made during the simulation was that the ratio between these two mechanical forces changed during the Earth's history, and was even inverted at regular intervals for continents. "Our calculations show that during the construction phase of a supercontinent, for instance Pangea 300 million years ago, continents are primarily driven by deep-mantle movements, while they are pulled by the surface due to subduction in phases where these supercontinents break up," Husson elaborates.

Subduction thwarted

The researchers have proposed an explanation for this observation. "When two continents come close to one another, the subduction that led to their convergence stops, leaving internal flows as the dominant force in the movement of continents and the creation of a supercontinent. Conversely, when a supercontinent is fully formed, new subduction zones appear, thereby allowing the mantle to release heat. It is these zones that continue the breakup of the supercontinent," Coltice suggests. The data gathered for the Earth also supports this idea.