You are here

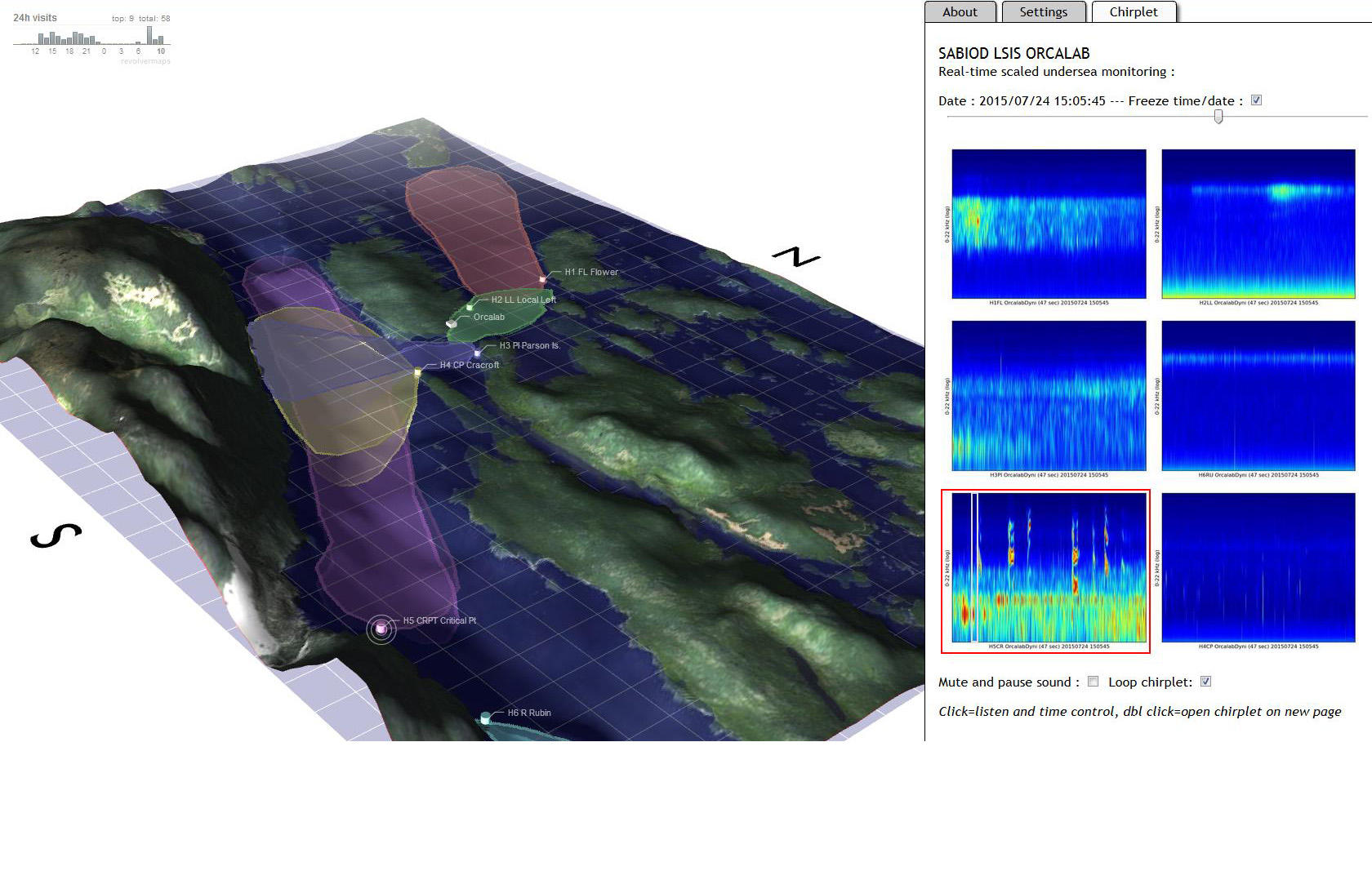

The Seas Have Ears

How would you like to live in a house with single-glazed windows next to a freeway? If the need to protect local inhabitants from road traffic appears necessary, if not self-evident, the same issue also applies to the seas. In our scenario, the local inhabitants are marine wildlife, ranging from whales to squid and the issue is anthropogenic noise, i.e., noise of human origin. And this noise is getting louder particularly since, as noted by Hervé Glotin, a specialist in bioacoustics and researcher at LSIS,1 marine traffic in the Mediterranean (cargo ships, freighters and cruisers) doubles every 3 to 4 years. While the deafening hum of these huge boats is familiar to everyone, this din is perceptible not only in the air but even more so in the water, thanks to the laws of acoustics (sound travels faster in water than in air and echoes off both the seabed and the surface).

A marked increase in noise pollution

This crescendo of acoustic pollution is not only caused by a rise in seagoing traffic, but also due to boats’ increasing speeds. “A large boat traveling slowly is less noisy than a fast jet ski,” says Glotin, who studies how the sounds and behavior of cetaceans are affected by man-made noise.

Cruisers are thus not the only boats responsible for such disturbance; the engines of smaller nautical leisure boats also play their part. To these must be added military exercises using sonar equipment, offshore drilling operations, seismic explorations using sonic canons for oil exploration, the offshore extraction sites themselves, and renewable marine energy sources, whether through the sound of propellers on large wind farms or that of the pile-driving needed to install them on the sea bed.

“Oceans are increasingly in need of management, whether in terms of plastic pollution or acidification. The question of marine noise has gradually emerged and the problem is far worse than was initially suspected”, says Hervé Dumez, director of the CRG2 at the École Polytechnique and the I3,3 a CNRS laboratory, which, in conjunction with Héloïse Berkowitz, a doctoral student at CRG, organized an international colloquium on the subject September 20th 2016 in Paris.

The problem is that such noise can create a disorienting source of stress for marine wildlife. For instance, in the Mediterranean waters between Marseille and Lavandou (southern France), there are 20 or so Tursiops truncatus, a species of large dolphins that only live in shallow water, and thus near the coastline. Their population is threatened by coastal tourist activities, and seems to have become less present near large towns. A study conducted by a student of Isabelle Charrier, a researcher who specializes in pinnipeds at NeuroPSI,4 had the objective of analyzing variations in the behavior of fur seals in Australia in response to playback of boat noise. It showed that at great amplitudes, their vigilance was heightened to such an extent that it prevented all other parallel activities such as nursing their young.

Wildlife deaths linked to noise

The stress induced by acoustic noise can be fatal to certain animals, occasionally in a more direct manner. One such example are the diving accidents observed in bottlenose whales: these cetaceans, highly sensitive to the noise of military sonar and mineral exploration equipment, dive down from the surface without respecting decompression stages, which causes lethal embolism. Yet these mammals are “expert divers,” insists Charrier. Such accidents are extremely rare in environments lacking man-made noise. “Among groups of walruses on land or on ice flows, boats or even helicopters, or low-flying planes, may also cause crowd reactions comparable to those seen in humans. All the individuals concerned rush away from the water, and in the ensuing panic, young animals end up being completely crushed. Such stampedes have already been observed in Alaska, with hundreds of deaths,” says the researcher.

While fish larvae develop less slowly in noisy environments, says Glotin, the impact of sound pollution is far greater in animals that rely on acoustic signals to move and to detect their prey, as is the case with odontoceti (toothed whales). Internal lesions are rare, since this would involve extremely close contact between the animal and the source of noise and high acoustic pressures. However, certain forms of noise disturbance can affect their auditory system, even temporarily. Such injuries result in animals beaching or colliding with boats due to their inability to analyze the environment in which they are living, or due to malnutrition from their diminished ability to detect prey.

In mysticeti, or baleen whales, communication between individuals of the same species may also be affected. Noise decreases the detection distance of blue whales, says Glotin, but also reduces the size of their communication networks. This results in more limited gene pools and increased fragility of the species, constituting a potential threat to survival. In the same way, the songs of humpback whales change very quickly: “If the propagation of whale songs is affected by anthropogenic noise, this could isolate any individuals whose acoustic production has not adequately adapted.” Failing to sing in tune within the normal register thus decreases their chances of reproduction.

Makeshift solutions

The other problem is that there is no clear solution to curb these noises. While France has acknowledged sound pollution as a form of marine pollution since 2010, no clear regulatory framework exists. Not all species are affected by exactly the same noise. Measurements made by the Bombyx acoustic buoy,5 and which require further investigation, show that the behavior of sperm whales is affected by the presence of noisy boats to a lesser extent than that of striped dolphins, asserts Glotin. It is therefore not enough to impose a maximum decibel level, by regulating boat speeds for example, since an extremely silent boat may also surprise animals at the surface of the water. Many common fin whales have thus been cut in half by ships they did not hear; “the motor is located at the back and the prow is the silent point of the boat,” points out the bioacoustic specialist. Low-level noise may occasionally be used to scare away animals from a given zone before extremely noisy operations are initiated.

As for pile-driving for wind turbines and the construction of a coastal road on Reunion Island for instance, “bubble curtains” can be used as a noise wall to reduce the propagation of acoustic waves, although these sheets of air bubbles attached to one another are only optimal in calm seas. Another relatively easy-to-use protocol mentioned by CRG doctoral student Héloïse Berkowitz is the “marine mammal observer” system which involves monitoring animals in the vicinity during operations. Yet this system becomes less effective when work continues through the night or when the animals are submerged below the surface.

“These are makeshift solutions and the approach will probably remain highly pragmatic, if only because noise management involves a number of different stakeholders, several industries, scientists and public authorities. A compromise is currently being sought between necessary human activities and protection of animals,” says CRG and I3 director Dumez. This is why, according to Glotin, it is essential to prepare animal behavior maps, both under conditions of zero acoustic pollution (he is currently directing a thesis on this subject concerning an unspoiled stretch of the Chilean coastline with 50% of cetacean species), but also as a function of the human noises imposed upon them (e.g., ocean liners from Seattle to Alaska that cross paths with pods of killer whales). This is the only way that industrialists can provide realistic impact studies and give marine life the sound relief it needs.

- 1. Laboratoire des sciences de l’information et des systemEs (CNRS / Université Aix-Marseille / Université de Toulon), head of the Scaled Acoustic Biodiversity MI CNRS project (http://sabiod.org)

- 2. Centre de recherche en gestion.

- 3. Institut interdisciplinaire de l'innovation (CNRS / Mines ParisTech / Télécom ParisTech / Ecole polytechnique).

- 4. Institut des Neurosciences Paris Saclay (CNRS).

- 5. Collaboration between UMR, CNRS, LSIS et MIO, IUF, TMP and Parc national de Port-Cros.

Explore more

Author

Daphnée Leportois is a French journalist who has worked for several publications including Slate, Metronews, and Le Plus.