You are here

The Birth of Color Photography

Vase with begonia, tulip and glass of wine. The title is mildly interesting at best and the subject even less so. But take a closer look: this is in fact one of the first color prints in the history of photography.

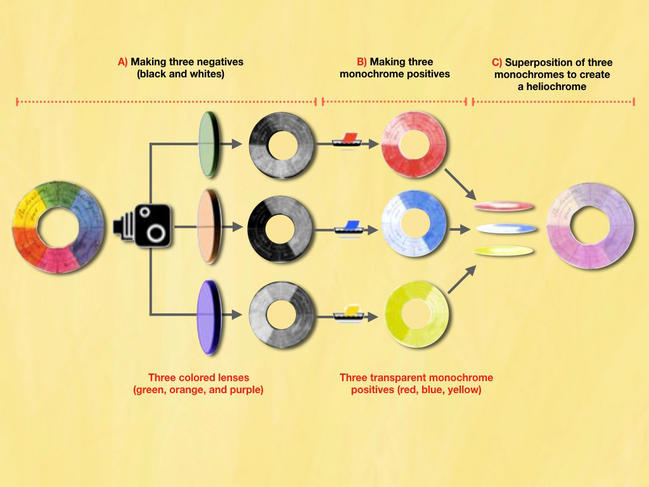

It was taken in 1879 by a certain Louis Ducos du Hauron. Or rather it was taken three times,1 since the procedure he described is based on a form of the three-color process that he called heliochromy with carbon pigments. It involves taking three photographs using three different color filters—in this case green, orange and violet. Positive prints containing yellow, red and blue pigments are then produced from the original negatives and superimposed to recreate the actual colors of the subject (see diagram). This inventor, practically unknown to the general public, was born in 1837 and died in the town of Agen, whose museum today possesses some of his works2 and has the delicate task of conserving this fragile and historically priceless heritage.

Fading history

“This still life is one of the 20 or so photographs by Ducos du Hauron that we have at the museum,” explains Adrien Enfedaque, the new curator of the Agen Museum, before informing us that these items are generally kept in the storage.

“They are far too fragile to be exhibited. Several of them are crinkling, and in some of the photographs the thin layers are coming apart. We simply don’t have a suitable room to put them on public display.” Moreover, no one knows exactly what type of room is suited to the extremely fragile nature of these works: an extremely low-light environment will doubtless be needed, although the exact level of lighting remains to be defined.

It is in fact with a view to establishing suitable conservation protocols that almost 6 months ago, some 15 items were sent to the Centre de recherche et de restauration des Musées de France (C2RMF)3 in Paris. Here, they are being analyzed by a multidisciplinary team of chemists, historians and conservators4 and compared with other prints produced during the same era in order to better understand the chemical processes and the pigments used, and to analyze their deterioration—in other words, they are being minutely studied to learn how they may be best conserved.5

A limited opus

“Louis Ducos du Hauron produced only a small number of images throughout his life. He began in the early 1860s and continued up to his death in 1920,” explains Jean-Paul Gandolfo, professor and specialist in early photography at the École nationale supérieure Louis-Lumière in Paris. The body of work being studied consists mainly of landscapes and reproductions of paintings, with the latter being a lucrative subject for the photography market at the end of the 19th century. “But the choice of still life subjects, or more generally, static subjects, was also dictated by the low sensitivity of the surfaces used and by the need to take three consecutive pictures with rigorous positioning constraints during the positive print production stage,” he adds, with particular reference to the Vase with Begonia.

The quest for reproducibility and the 19th century Eldorado

This restrictive need to take multiple photographs to produce a single image characterizes the first attempts by science to immortalize an image; it must be remembered that in 1879, photography was still only 50 years old. The very first photograph, The View from a Window at Le Gras, by French inventor Nicéphore Niépce, a view taken from his bedroom window which required an exposure time of no less than one full day, was taken in 1826. The process, which involved the use of a tin plate covered with bitumen of Judea (a type of natural tar), was improved upon and disclosed in 1839 by Louis Daguerre, whose initial attempts show empty Parisian streets, with all moving human subjects being entirely effaced thanks to the excessively long exposure times. However, these non-reproducible daguerreotypes did not fully meet the needs of the day. With his calotype presented in 1841, Englishman Fox Talbot introduced a technique enabling the creation of a paper negative from which as many positive prints as desired could be reproduced, thus presaging future developments in photography.

The scramble for color

The history of color photography remains somewhat unclear. Certain authors maintain that the first color photographs were taken in 1850 by American Baptist pastor Levi Hill. However, this assertion continues to be contested. “The extremely weak colors in these Hillotype photos are vastly inferior to the results obtained by Ducos du Hauron,” suggests Gandolfo. Yet his observation is not prompted by national pride; while he remains unconvinced by the efforts of Levi Hill, the experiment by physicist James Clerk Maxwell in 1861 was the first to demonstrate an additive three-color process using three magic lanterns (with red, green and blue filters). “This was an experiment performed by the young Maxwell for the sole purpose of validating his scientific approach.” Was Ducos du Hauron, who wrote down absolutely everything he did, aware of this experiment? Although the two events took place at around the same time—Ducos du Hauron’s first color photograph dates from 1869—no historical evidence has yet surfaced confirming that he had such knowledge.

However, unbeknown to him, another inventor—this time a fellow Frenchman—would steal the limelight on May 7, 1869, just as Ducos du Hauron was preparing to present his color photography method before the French Photography Society. The man in question was poet Charles Cros, who, on the very same day, even though they had never met, described the exact same method. But any argument about which of the two processes came first soon dissipated and the two men struck up a firm friendship.

“They devised solutions to the problems posed by three-color color photography that shared some common ground while nevertheless differing greatly,” explains Gandolfo. “Charles Cros did not devote the rest of his life to the subject, and from 1869 increasingly turned to a strictly theoretical approach. Ducos du Hauron very quickly realized that Cros had little concern for the industrial prospects.” During the 1880s, Charles Cros resumed the studies of his younger years and proposed a new process based on dyes, while Ducos du Hauron remained attached to pigment techniques.

A synchrotron for heritage

It is in fact precisely because of his investigations concerning pigments and chemistry—which frequently varied from one print to another—that Ducos du Hauron’s work is so difficult to understand and conserve. “Even though these prints have all been painstakingly labeled and documented by the inventor, we still not do not have the technological understanding that would allow us to identify the materials used in each print so as to interpret the mechanisms responsible for their deterioration. Today, this heritage, the oldest items of which are over 150 years old, is showing signs of fragility that underscore the urgency of the situation,” says Gandolfo, who clearly hopes that these studies will result in improved conservation of these works.

Twenty-seven prints were analyzed using non-invasive methods in order to determine the techniques and components used. Samples from three of these photos6 are now in the hands of Marine Cotte, a researcher with the Laboratoire d’archéologie moléculaire et structurale (LAMS),7 who led the work at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble. “This is the first time I have worked on a photograph,” says the chemist, who is more usually involved in the analysis of fragments from paintings. “Wherever possible, it is always better to analyze works of art in situ without sampling. But occasionally, especially when seeking to obtain information on material contained in the inner layers, it may be necessary to remove micro-fragments. In this case, by using x-ray or infrared microscopes at the synchrotron installation, it is possible to examine the material at resolutions down to micron levels and to observe every minute detail.”

“These three pieces show varying degrees of deterioration, occasionally with separation, exposing the underlying layers,” she explains. “In this case, we were able to obtain samples from layers that are not normally accessible.” The results are impressive: in two cases, the results of the analyses are fully consistent with the procedures described by Ducos du Hauron in his correspondence. The most significant results were obtained with infrared microscopy, since “this analytical approach is far more sensitive to organic compounds, resulting in extremely clear markers,” adds the researcher. “Amongst other materials, we have found gelatin, collodion and resin, as well as pigments such as Prussian blue, which are readily identifiable using this method. We have shown that infrared microscopy may be extremely useful in characterizing old photographs,” explains Cotte.

This type of research may lead to an understanding of how the objects or pigments were manufactured (picture-making techniques, heating, chemical or physical reaction, etc.) and of the types of deterioration to which they may have been subjected (due to light, the environment, previous restorations, and so on).

“An unlucky inventor”

And his photographs had already begun to deteriorate in his own lifetime. “Ducos du Hauron was critical of some of his early processes, noting for instance that ‘I substituted such and such a pigment with another since it was not stable in light,’” points out Cotte. “He took great pains to improve long-term stability.” Indeed, when the inventor set out his theories, he was faced with two major obstacles. First, his contemporaries were not convinced that the three-color approach was the most suitable from a physics standpoint, and second, he failed to obtain the support he required.

“It is pretty much the classic tale of the ‘luckless inventor.’ He was working alone and lived in a provincial town, which was not particularly conducive to innovation in the 19th century; many inventors lived in the Paris region and attended meetings of the numerous learned societies present in the capital,” says Gandolfo. The second obstacle, “which compounded his misfortune,” was that he required new materials produced by industrial partners—particularly regarding dyes and pigments—but this condition could only be met much later, at the start of the 20th century. Such sensitizing coloring agents, essential for the preparation of photographic plates meeting the requirements of three-color processing, were introduced by the German chemical industry, but not before the turn of the century.

“He was penalized by the lack of recognition in terms of scientific validation and also on the technical level, where his inventions were ultimately still too far advanced to be readily turned into an industrial success.” Moreover, his patents, which were valid for 15 years at the time, were never extended, and his innovations were developed by others, most famously by the Lumière brothers, who launched the trichrome process and color photography during the industrial era under the name of autochrome.8 Ducos du Hauron witnessed the spread of color photography during the final years of his life, but he received no financial rewards for his efforts.

“The incredible thing,” concludes Gandolfo, “is that trichromy—a process so roundly criticized at the time, with its detractors including part of the scientific community—managed to impose itself down the years and has been transposed intact into the digital world. On the surface of digital sensors, in inkjet printers and on cinema screens, we still find today the triads of colors following on from the devices used by Ducos du Hauron in the 19th century.”

- 1. There are several extant versions of the Vase with Begonia.

- 2. Some 100 prints are shared, among others, between the Nicéphore-Niépce Museum in Chalon-sur-Saône, the Musée d’Orsay, the Académie des Sciences, and the Musée des Beaux-Arts d’Agen. A number of prints are also kept at George Eastman House in Rochester in the United States, the world’s oldest photography museum.

- 3. Museums of France Centre for Research and Restoration.

- 4. A team comprising scientists and conservators from the ESRF, CNRS, the C2RMF, the Musée d’Orsay, the École nationale supérieure Louis-Lumière, the science and engineering faculty of the Sorbonne University and Chimie Paris Tech, as well as an independent photograph conservator-restorer.

- 5. From Obscurity to Light: Rediscovering Ducos du Hauron’s Color Photography Through the Review of his Three-Color Printing Processes and Synchrotron Micro-Analysis of his Prints, Marine Cotte, Tiphaine Fabris, Juliette Langlois, Ludovic Bellot-Gurlet, Françoise Ploye, Natalie Coural, Clotilde Boust, Jean-Paul Gandolfo, Thomas Galifot, Jean Susini, Angewandte Chemie, published online in March 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201712617

- 6. Vase with Begonia, Cliffs Close to Algiers, and an unidentified fragment.

- 7. LAMS (Laboratory of molecular and structural archeology).

- 8. He was also the inventor of anaglyphs (images with a three-dimensional appearance), and he filed patents for processes that predated the Lumière brothers’ cinematograph.

Comments

Log in, join the CNRS News community