You are here

A Sociologist in the Realm of Dreams

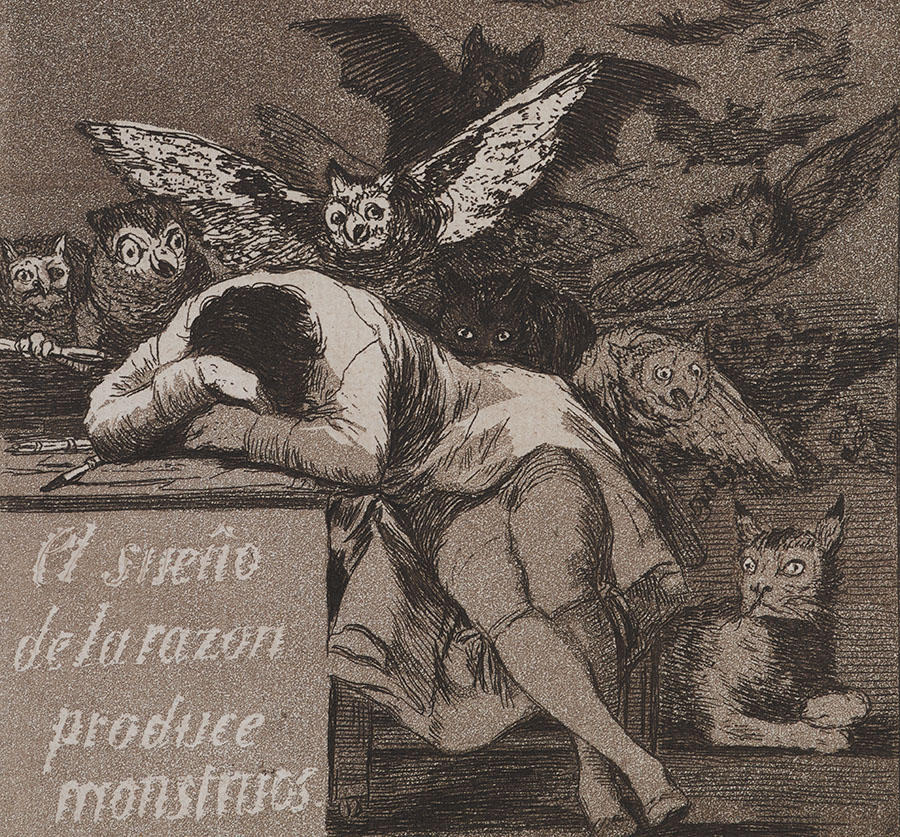

In a broad synthesis published this year,1 you propose to make the ‘dream object’ an integral aspect of the social sciences. You describe this object as a ‘castle surrounded by brambles and guarded by a dragon’. The dragon and brambles are psychoanalysis, which has dominated the interpretation of dreams since Sigmund Freud. What is the reason for this near-monopoly?

Bernard Lahire:2 It’s an extremely powerful model, which remains strong in many respects. Although Freud is somewhat out of favour in the neurosciences, many studies in that discipline and in experimental psychology show that he was right on various points—for example, ‘day residue’, or images of the previous day that become part of a dream and that the dreamer can recognise upon waking. Freud interviewed hundreds of patients and succeeded in identifying some fundamental mechanisms. In this sense, he is the Champollion of the language of dreams, allowing today’s linguists to work on the metaphors that structure dreams. But why such a monopoly? Quite simply because nothing better had been proposed yet.

In your opinion, what is Freud’s essential contribution to the science of dreams?

B.L.: Freud, at first, was what we would now call a neurophysiologist. Then, for his work on ‘hysteria’, he began gathering information about the dreams of the young women he treated, and realised that the realm of dreams could serve as the foundation for a theory of the psychic mechanism—the starting point of psychoanalysis. At that stage, Freud began reading voraciously everything that had been written on the topic. He went back to the ancient Greeks, in particular Oneirocritica by Artemidorus Daldianus, to establish that dreams were not meaningless hallucinations, that they were not composed of totally random images triggered by electrical discharges in the brain during the night, as many scientists thought at the time. Freud developed a broad synopsis based on the fundamental hypothesis that dreams have meaning and can thus be interpreted.

By postulating that dreams are a social phenomenon, your book alters our perception of both dreams and sociology. Why are dreams so troubling that, as you put it, “sociologists close their eyes when their subjects fall asleep”?

B.L.: For many years, sociology excluded the individual from its objects of study, for the benefit of the group, the institution, broad statistical trends, etc. But the discipline has progressed since Durkheim, studying specific cases and life stories. Dreams are not only personal, but very intimate and decidedly singular: they take place during sleep, and every night each of us experiences new mental episodes that seem strange, incongruous and incoherent. It’s not like studying athletic or cultural practices. That said, Durkheim, the founder of sociology in France, worked on suicide, which I think sets a good example, even though I use a different approach, not distinguishing individual singularity as opposed to social life.

How do you consider a dream to be sociological material, a social object?

B.L.: Our dreams are based on an ‘incorporated’ past. We all have a history, social experiences that are part of us and contribute to the makeup of our personalities—what sociologists call ‘dispositions’. These include ways of seeing, feeling and acting, as Durkheim said, that are fairly stable, linked to the repetition over the course of a lifetime of relatively similar experiences, due to our individual backgrounds and the people we associate with (family members, classmates, co-workers, spouses, friends, etc.) for long periods of time. All of these social experiences accumulate within us, creating a sedimentation, not in the form of recollections but rather as incorporated memory. In most cases, we are not even aware that we have this in us. And once again it is social experiences, more recent, that reactivate this memory, making it resurface in transmuted form in our dreams.

You say that dreams bring forth the dreamer’s ‘existential problem’ in connection with their past. Actually, not many dreams fulfill the ideal associated with the word ‘dream’…

B.L.: Yes, we are far from the meaning of the term in expressions like ‘I dream of traveling around the world’. The great majority of dreams show that we’re mulling over our problems in the night. It’s no coincidence that we dream about people with whom we have an emotional connection (father, mother, spouse, co-workers, friends), even if they appear as other figures. I needed to call upon the concept of existential problem when I was working on Franz Kafka’s literary creative process. In fact, it’s a rather similar scientific issue. Writers transpose their memorable experiences in literary form. Kafka encountered a series of social contradictions that he portrayed in his work. The term ‘existential problem’ relates to preoccupation: we dream about what troubles us. Dream situations are problematic episodes from our past, reawakened by recent events.

How do these ‘trigger events’ work?

B.L.: In the course of the day, you see people, you hear things, and it triggers something in you. The process might last no more than a few seconds, before your mind suddenly abandons those mental representations to let you get on with what you’re doing. But those little occurrences can continue to occupy the brain and resurface at night, if they touch upon important elements in terms of the structure of your personality. In my book I cite an example from the sociologist Maurice Halbwachs, who was ‘mortified’ one day not to know the chemical substances in a medical prescription. That same night he dreamed that he was with former classmates from the Ecole Normale Supérieure who were talking about chemistry, and he couldn’t answer their questions. In the dream they had all received distinctions and he had not. The micro-event of the day conjured up an old fear of not living up to expectations.

You describe dreams as a ‘communication from oneself to oneself,’ beyond the constraints of social interactions…

B.L.: Yes, there is a high degree of implicitness in dreams. It’s a language of extraordinary economy. Because no one else is involved, there is no need for explanation, as I am both the creator and sole recipient of the dream’s images. It’s the shortest possible channel of communication. I often cite the example of old couples: all they have to do is exchange a glance, a single word or even utter a sound, and they know exactly what the other one is thinking. Understanding oneself is even easier!

Freud thought that dreams were an expression of censorship, of suppressed unconscious desires, whereas you postulate the exact opposite…

B.L.: Indeed, the fact that we are speaking to ourselves means that there is virtually no censorship. We can say what we think without fear of judgment. For example, you would never tell your boss, ‘You’re such an idiot’! You might do so within a group of trusted colleagues, but never in front of co-workers you don’t know that well, and so on. The closer you are to the people around you, the more you can let your guard down. In a dream this principle holds perfectly true, since you’re alone. What’s funny here is that, paradoxically, Freud’s mistaken hypothesis allowed him to proceed in the right direction. Astonished by the strange, bizarre language of dreams, he imagined that there was a kind of censorship at work, and that dreams were masking the real message, as people do in war or situations of oppression. He based his thinking on that model and claimed that censorship was the cornerstone of his theory, but fortunately it wasn’t so! Pursuing this false notion, he sought to ‘decode’ the language of dreams, and there he was on the right track.

In your book, you often mention the neurosciences. What role did they play in your analyses?

B.L.: I think it’s difficult to be a sociologist today without knowing how the brain works. Neuroscientists believe it is a kind of detector of regularities, and this corresponds perfectly to the functioning of dispositions. You’re a baby, you cry once and your mother immediately comes to see you. If the second time you cry she reacts in the same way, you have ‘learned’, in practical terms, that crying makes her come to you. The mechanism is essentially quite simple. As far as the unconscious is concerned, the contribution of the neurosciences is equally invaluable, since many sociologists still attribute far too much conscious awareness to individuals in their actions. Some think that because we have a brain, our every move is free, calculated and intentional. Yet Stanislas Dehaene, for example, maintains that consciousness is just a small trickle of thoughts. In fact, there is a huge body of non-conscious processes at work, predetermining our actions, our sensibilities, our annoyance or amazement, strongly conditioned by the series of experiences that we have accumulated since birth.

While psychoanalysis has a therapeutic purpose, is the sociology of dreams more political in nature?

B.L.: The biographical interviews that I conduct can produce therapeutic effects, without specifically intending to, but that’s not the main point. Concerning masculine domination, women tell me about men who are predatory, insistent, unsubtle—and the list goes on—because the social world constantly produces this type of situation and people. To put an end to it, it’s the social world—and not necessarily the individual—that needs to be changed. Essentially, the biggest difference with psychoanalysis is that, in the analysis of dreams, I look at all of the groups, institutions and social relations that give rise to ‘personal’ problems. I mention a case study collected by Frantz Fanon: if a black man dreams that he becomes white out of a desire for upward social mobility, it says something about the social structure around him. Fanon believes that, to address this type of neurosis, the relations between colonisers and colonised need to be abolished.

By upholding a multidisciplinary approach, far from the cliquishness and competition of the research world, you dream of broadening the scope of the social sciences. How do you intend to promote ‘unified’ research?

B.L.: Interdisciplinarity cannot be achieved at will. On the other hand, we need to get into the habit of looking beyond our own disciplinary base, and to make that part of the training of young researchers. For an object like dreams, I have read the work of psychoanalysts, linguists, neurobiologists, cognitive psychologists, historians, anthropologists… When I was investigating the trajectory of a painting by Poussin, I ended up reading texts on sacramental theology! I could have stayed within the comfortable confines of the sociology of art, but in that case I would never have been able to complete my book on the topic.3 The history of science is full of useful lessons along these lines. When you think about how daring Darwin was… He himself was terrified by what he discovered! But he had a driving desire to understand the evolution of life, and 150 years on, his ideas still hold. This type of approach is increasingly difficult now that the sciences are so compartmentalised, with sharp division of labour and hyper-specialisation. What Freud did was put the pieces back together! I sought to do the same thing in Ceci n’Est Pas qu’un Tableau and L’Interprétation Sociologique des Rêves. Thinkers like Durkheim, who had to develop their discipline from scratch, reached out in all directions! I would like to give young researchers, who are highly professionalised but modest in their ambitions, a taste for scientific risk and adventure, encourage them to explore new avenues and conquer new territories. Remember science is a fantastic adventure!

- 1. L’Interprétation Sociologique des Rêves, La Découverte, 2018. A second volume will be released in 2020.

- 2. Bernard Lahire is a professor of sociology at the École Normale Supérieure in Lyon, a senior member of the Paris-based Institut Universitaire de France and deputy director of the Centre Max-Weber (CNRS / Université Louis Lumière Lyon 2 / ENS Lyon / Université Jean Monnet Saint-Etienne). He was awarded the CNRS Silver Medal in 2012.

- 3. Ceci n’Est Pas qu’un Tableau. La Découverte, 2015.

Comments

Log in, join the CNRS News community