You are here

How Manga Conquered the World

For the first time, the Angoulême International Comics Festival will offer a manga translation prize (launched by a Japanese patron, the Konishi Foundation). Is this an indication of the growing importance of this Japanese art in France and worldwide?

Cécile Sakai:1 It strikes me as a sign of maturity. Translation is a highly absorbing work, fascinating but very austere, and whose true value is not recognized either from an artistic or financial standpoint. From this perspective it's a very good sign. Manga has continually featured at Angoulême over the last 7-8 years, whether it was in the form of a prize or an exhibition. The authors of manga—mangakas—are also present in the judging panels, conferences... Besides, the organizers of the festival often travel to Japan, in order to meet with authors and publishers, and visit the Manga Museum in the heart of the former capital, Kyoto. The museum was created in 2006, and contains approximately 300,000 volumes. More evidence of maturity...

When does the museum trace back the manga to? And whom to, Tezuka or Hokusai?

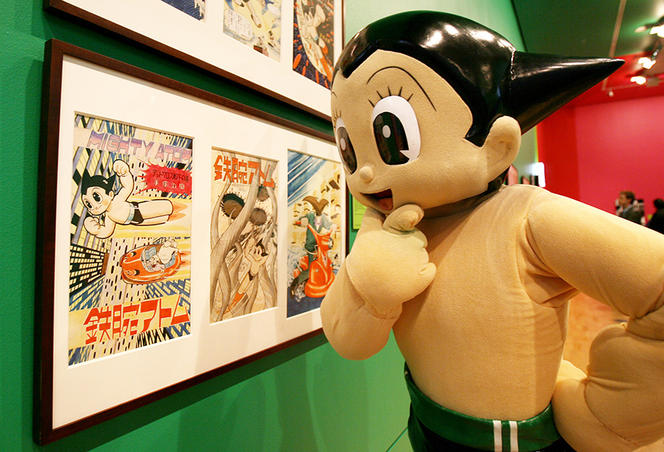

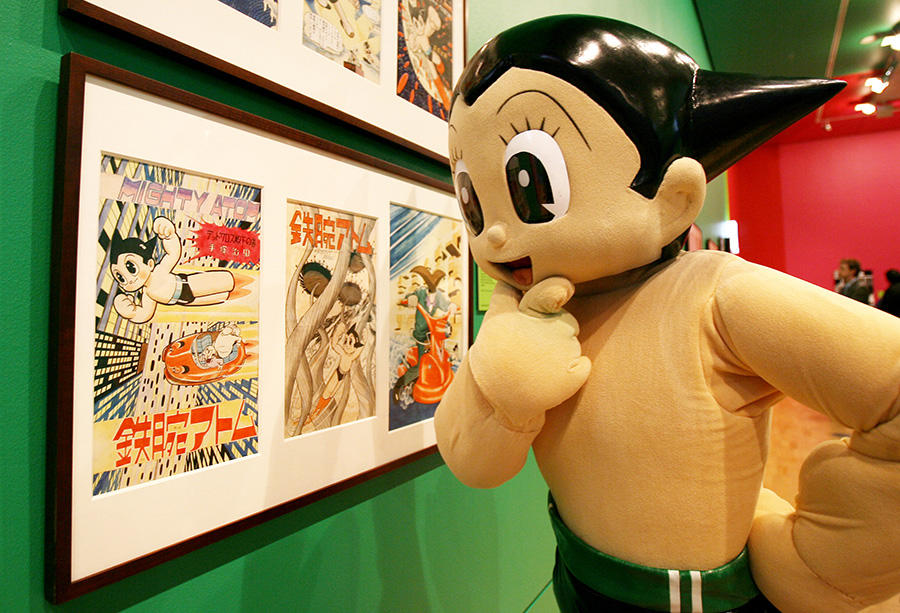

C. S.: There are a number of influences behind the manga, including the four-panel comic strips of US daily newspapers, a principle that was adapted in Japan even before the Second World War. The term manga—which literally means free drawing—was popularized in the early 19th century by the master printmaker Hokusai. But the founder of the modern manga is Osamu Tezuka, who in 1952 created the little Promethean robot Astro Boy, and whose manga were later made into cartoons.

Through his great fictional narratives marked by humanism and his criticism of the contemporary world, Tezuka broke away from the influence of US comics, by developing types of characters represented according to a certain Western model, with large eyes and a small nose and mouth. He freely divided the panels and action, performed many graphic explorations and his appropriation of space was considered more daring than in comics.

I should point out that Japanese is an ideogrammatic and phonogrammatic language, with two different syllabaries, which are supplemented by 2,000 ideograms (sinograms from Chinese). It is therefore a composite written language, broadly explored by authors of manga, especially through the use of onomatopoeia.

One of the characteristics of manga is that dialogue is punctuated by a system of onomatopoeia that is not just auditory, but also visual, gestural, and psychological. This is achieved through formal and linguistic creations, many of which by mangakas, with some having become a part of standard vocabulary.

Are manga sales as robust today?

C. S.: It's important to keep in mind that in Japan, manga initially appears in cheap, hefty periodicals. Shōnen Jump, Shōnen Magazine, and Shōnen Sunday are the three best-selling weeklies, and are owned by the three largest publishers. The stories are published by chapter, which explains the length of the series. For the best-known titles in France, such as DragonBall, One Piece, and Naruto for example, this includes 80-90 volumes each, as new sequences appear week in, week out, year after year. These sequences are then collected and published again in book format. This is what is translated in France.

In Japan, these pre-publication sales are declining, dropping from 6-7 million weekly during the 1990s to less than 2 million today. This is most likely the end of a cycle that began in the mid-1960s. There is now a preference for the book format, which is easier to preserve. The choice is also more diverse, for instance with the so-called "visual novels," graphic novels with recurring characters that feature in paper, video, or interactive formats, and take up entire aisles in gigantic bookstores. This is what appeals the most to Japanese youth today.

What about the distribution of manga in France?

C. S.: We are in a period of maturity. The export of manga to France took place in several stages. The first was with the cartoons that were broadcast on children's programs during the 1980s, which were viewed by a large audience. It was controversial at the time, as people found the cartoons violent and vulgar, with much criticism coming from teachers. Yet this audience was the key to its success, for these children developed a passion for manga and began to buy them in books and translations, sometimes even ending up enrolling in Japanese universities and becoming specialists!

In terms of market evolution, after these television cartoons came the first systematic translations in the 1990s by France's primary publishers, comprising Glénat, Kana, and Pika. They chose the most important authors and translated them on a massive scale, as each title often involves 80-90 volumes. It takes up space! The simultaneous success of new animated films, especially those produced by the Ghibli studio (Totoro, Spirited Away, etc.), also strengthened this trend. In the 2000s, the market reached fast cruising speed. Since the 2010s, the Japanese language has ranked second in statistics regarding the translation of foreign language titles into French. In 2016, English represented approximately 60% of translated titles, and Japanese scored 12.5% (according to Livres Hebdo), far ahead of German, Italian, and Spanish. These considerable figures are due to manga. In the early 1990s, when most translated work was literary, translations from Japanese represented 1.5-2% of the total (still in number of titles), which raised the question of whether manga and literary production could be lumped together in statistics...

These are "paper" statistics, and among the many factors for the transformation of today's market, one must take into account the increasing role of e-books. Today there is an "official" digital product range that complements the catalog of some publishers, along with "unofficial" titles, which more or less amounts to pirating, as some individuals—who incidentally are enthusiasts—appropriate certain titles, translate them, and pre-publish them in digital format, doing so without authorization. It is a global movement of free, personal, and virtual translation.

And you are also a translator?

C. S.: Yes, I'm a literary translator, but I know manga well for practical reasons: I have been teaching modern and contemporary Japanese literature at the Université Paris Diderot for a long time. Since the 2000s I have supervised many PhD theses, especially on manga, which draws 60 to 70% of students pursuing Japanese studies today, along with the cartoons they discovered as young children. As I explain to my students though, literary translation is very different from translating manga. In my classes, I compare it to film subtitling, because in my experience translating manga is closer to adaptation than translation. As in cinema, words cannot take up too much space, and reading speed must also be taken into account. Unlike a written text constructed sentence by sentence, this type of medium requires a relatively quick form of reading that cannot be hindered by long wording. Its constraints are therefore similar to those in film subtitling.

How do you translate a visual onomatopoeia?

C. S.: There are different methods, depending on the translators and editors. Some choose absolute authenticity: manga have become such a part of our lives that having a few sinograms or Japanese syllabaries here or there doesn’t bother anyone, and so the onomatopoeia will stay as is. Some will dub the original onomatopoeia with a short translation. Yet others will completely transform it by replacing it with letters, sometimes at the risk of failing to convey its meaning.

Can comic books from Western artists, for example those by French authors, be called "manga"? Are they read in Japan?

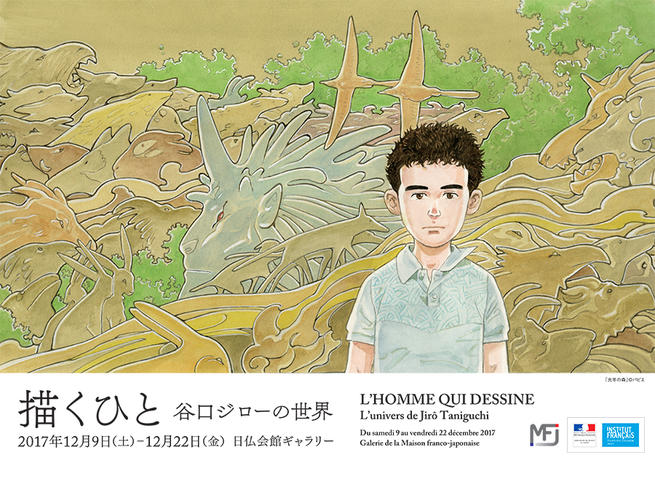

C. S.: It's a fairly complex question. French-Belgian comic books, such as Tintin and Astérix, have had success in Japan, influencing certain mangakas. However the most widely known are important authors such as Moebius (Jean Giraud) or Enki Bilal, François Schuiten and Benoît Peeters, sometimes through co-authored works. I would like to cite Jirô Taniguchi (1947-2017), who sadly passed away last February, and for whom we suggested an exhibition in December 2017 at the gallery of the Maison franco-japonaise. He has been celebrated in France, notably at the Angoulême festival, and his work has been adapted for film (A Distant Neighborhood). He also collaborated with Moebius on Icaro, among others.

Other lesser-known authors, whether French, Chinese, Thai, or Korean, work in the manga style. For instance, Korean comics books, called manhwas, are translated into English and French. In France, they could be called manfra... But France is the second largest market for Japanese manga, after Japan but ahead of the US and the rest of Asia. These figures are for print runs. The immediate risk is saturation. Today most significant manga has already been translated, and even retranslated! Some also feel that there are fewer remarkable authors today, even in Japan. The sector needs to reinvent itself...

A declining creative activity, that's fairly rare...

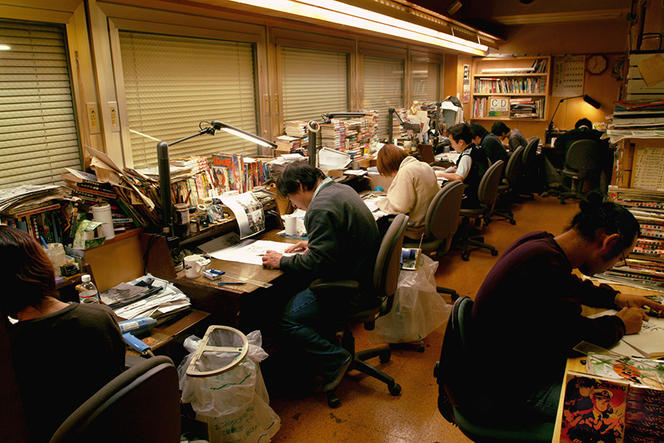

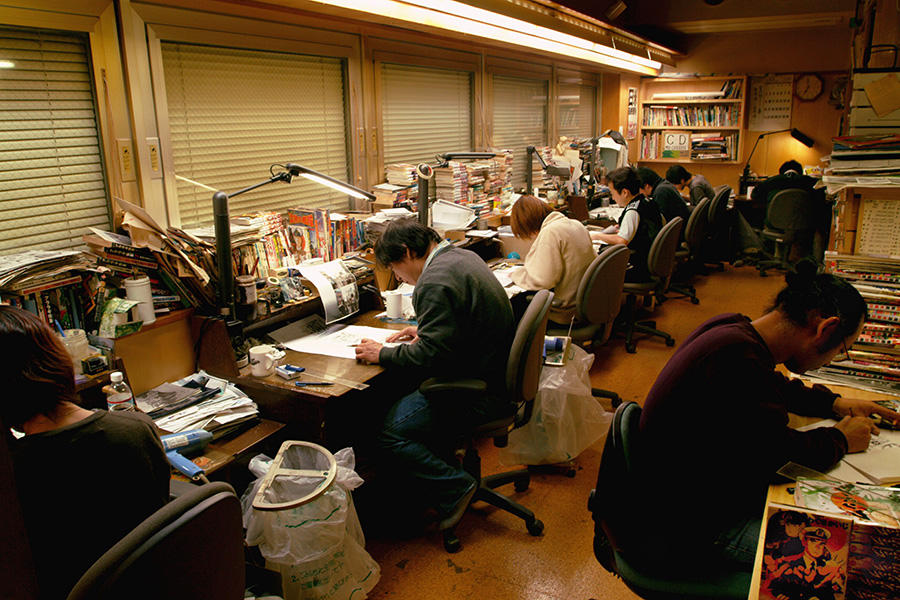

C. S.: Many authors and publishers put the blame on working conditions. To truly start out as authors today, mangakas must take numerous tests, and mostly be part of an enormous manga production group. The activity thus becomes a wearying collective task that has nothing individual about it, and increasingly resembles an assembly line.. Attention is lavished on a few famous names that hide entire factories of very poorly paid mangakas. Such circumstances are not very conducive to the emergence of new talent. All of this is taking place in a context of saturation in the Japanese market, with a marked decrease in the number of readers.

- 1. Director of the Institut français de recherche sur le Japon at the Maison franco-japonaise, a Tokyo-based joint institution that specializes in HSS (one of five CNRS joint units with a French research institute abroad (UMIFRE-MEAE) in Asia). The former IFRE created in 1978, became an UMIFRE in 2007. In 2009, in connection with the USR 3331 service and research unit, it was associated with the 18 CEFC UMIFRE located in China. http://www.mfj.gr.jp

Comments

Log in, join the CNRS News community